It’s not just the pacing that bothers me, though. There’s also the idiotic belief shared by readers and editors that the death of a major character is all that makes comics “believable.” (Because verisimilitude is, of course, the most desirable element in a story about people with supernormal powers who fly around in capes and long underwear, calling themselves by names that would make a Japanese PR Firm blush.) And of course there’s the current fascination with moral relativity, making good characters suddenly turn bad, coupled with a harsh, judgmental spirit in the writing, so some good characters become despised scapegoats who can’t get a break, while mass murderers are hailed as heroes.In particular, I’ve held for years a very low opinion of what’s been done with one of my all-time favorite comics, the Avengers. For me, it just seemed to devolve into a shock-a-minute depression fest in which character integrity took a back seat to making fanboys scream, “OhManOhManOhMan I can’t wait to buy the next issue and the trade!”

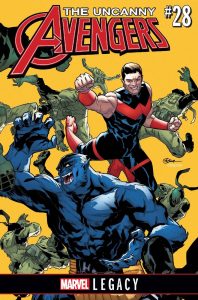

I was cautiously optimistic when it was announced that a new book called Uncanny Avengers was coming out. It had a cast featuring both Avengers and X-Men, and it prominently featured Marvel second-stringers Havok, Rogue and Scarlet Witch alongside Captain America, Thor and the annoyingly omnipresent Wolverine. I was, unfortunately, so disappointed with the opening four-issue story arc that I was going to stop reading the book. It was full of characters blaming the Scarlet Witch for the fact that she was badly written by Brian Michael Bendis, it featured the corpse of Professor X being hauled around with the top of his head missing, and it featured unnamed characters being killed with no notice or mourning. It just wasn’t what I wanted to read.

My son asked me to read the latest issue, however, because the ending bothered him and he wanted to discuss it. So I read it, and I have to say it’s the best in the series, probably the best issue of anything with Avengers in the title that’s been published in years. (Although Dan Slott tried hard on his run on Mighty Avengers to re-capture some of the greatness of years past.) There’s a scene with Captain America and the Scarlet Witch the likes of which we haven’t seen since Roy Thomas wrote the book in the 1960s, and it’s refreshingly free of reminders that she allowed herself to be used by super villains to perpetuate bad Summer “event” storylines. There’s a seen where Wolverine recruits Sunfire to the team, in which Wolverine is, for the first time in thirty years, not annoying to me. (Granted there’s a detour into an account of how he just drowned his son in shallow water and buried him that I could have done without. As a parent, I really hate how often comic heroes children are killed, especially by their own parents. It suggests that the creative teams are either very young, stupid and single, that they’re middle-aged get-a-lifers in no danger of having a child, or that they’re screwed up people who really hate their kids.)

I won’t give the details of the ending and how it bothered my son. Suffice to say it involves death and surprise, but I pretty much glossed over it. It’s an easily undone death. The issue was low on shock, high on characterization, and featured the return of light-hearted characters Wonder Man and the Wasp. It bodes well for the future of the series.

But my favorite part involved Havok, brother of Cyclops of the X-Men. Cyclops is now a murderer and a super villain, because, again, we love our moral relativism. The point of the team he leads is to foster unity between “normal” humans and mutants. After shooting down an offensive suggestion by Captain America that they hide their more notorious mutant members for a while (remember that Cap took orders from a Commander-in-Chief who thought it was acceptable to put US citizens in relocation camps based on how they looked), Havok tells members of the press that he would prefer they stop using the “M-word” and just refer to the mutant members of society as people, with no special labels. When the dimwit reporters ask, “Well then what do we call you?” (because dimwit reporters can’t live without labeling people) he responds, “Call me Alex.”

It’s a wonderful rejection of group-think. Havok is standing up and saying, “I’m a person, not a label. Don’t use the label, because it tends to make you think of me as something other than a person. My identity is mine, not some group’s, and you may call me by the name which identifies one unique individual.” Such individuality is refreshing in a day when we only seem to want to recognize people as parts of groups, not as individuals.

I understand this speech has created controversy, that it’s seen as Havok rejecting his mutant identity, that he’s ashamed of what he is, that he’s like a gay person going back in the closet. I don’t buy that. There’s a time for claiming a label and saying, “Why yes I am this thing or that thing, and I am proud of it.” There’s also a time for saying “that adjective you use to describe me is a part of my identity. It is not my whole identity. If it gets in the way of you treating me as an equal, then don’t use it.”

I support marriage equality, and I appreciate the thoughtful arguments of friends who think it’s appropriate to keep using the term “gay marriage,” so that we don’t forget what it is that some people are trying to deny, even though we don’t say, “I’m getting straight married.” I think that’s a good point. But that’s labeling a concept, a practice, not a person.

Labels are dangerous, because people become obsessed with them. They make it too easy to pre-judge and say, “That person meets this criteria, so I can dislike him without investigating further.” That’s something we shouldn’t allow ourselves to say. The speech made by Havok herein makes a stab at letting people know that, and I congratulate the writer, Rick Remender. Keep writing issues like this one, Rick, please!

This series continues to delight. Johnny Storm is now a billionaire, heir to Reed Richards’s patent earnings. Of course, it’s pretty clear Reed’s on his way back, but still, it’s an amusing turn. Quicksilver is being written as something other than angry, for a change. If I’m honest, Rogue as team leader still feels forced to me. Is there a female X-Man (irony unintentional) who isn’t leading her own team? I get it, it’s long overdue that we had equality on that score, but it still feels a bit forced. On the other hand, anything that puts Jean Grey, Rogue, Kitty Pryde and Polaris into the limelight is okay with me.

This series continues to delight. Johnny Storm is now a billionaire, heir to Reed Richards’s patent earnings. Of course, it’s pretty clear Reed’s on his way back, but still, it’s an amusing turn. Quicksilver is being written as something other than angry, for a change. If I’m honest, Rogue as team leader still feels forced to me. Is there a female X-Man (irony unintentional) who isn’t leading her own team? I get it, it’s long overdue that we had equality on that score, but it still feels a bit forced. On the other hand, anything that puts Jean Grey, Rogue, Kitty Pryde and Polaris into the limelight is okay with me.

A satisfying conclusion to the Graviton story, although the resolution of Rogue’s brief brush with madness at the climax is a little abrupt. The story celebrates teamwork, which is what the Avengers are all about. And the words “Fantastic Four” are actually uttered! Johnny Storm is a welcome member of this team, but it would be nice to have him back where he belongs. The subplot where an attorney is trying to catch up with him, and surprises him at the end of a boxer-clad battle, is appropriately funny and mixes the mundane with the fantastic in the way the best Marvel tales always have. I’m reminded of the first appearance of Henry Peter Gyrich (although that was more sinister) or the earlier Avengers tale in which Janet Van Dyne (the original Wasp, and still a member of this team) inherited her father’s millions.

A satisfying conclusion to the Graviton story, although the resolution of Rogue’s brief brush with madness at the climax is a little abrupt. The story celebrates teamwork, which is what the Avengers are all about. And the words “Fantastic Four” are actually uttered! Johnny Storm is a welcome member of this team, but it would be nice to have him back where he belongs. The subplot where an attorney is trying to catch up with him, and surprises him at the end of a boxer-clad battle, is appropriately funny and mixes the mundane with the fantastic in the way the best Marvel tales always have. I’m reminded of the first appearance of Henry Peter Gyrich (although that was more sinister) or the earlier Avengers tale in which Janet Van Dyne (the original Wasp, and still a member of this team) inherited her father’s millions. I’ve made no secret of the fact that I’m not much of a fan of modern comics. I don’t like the pace of the storytelling, where everything is so obviously plotted to fill a six-or-twelve-issue trade. Often nothing significant happens in a single month’s issue, and even more often, the thirty-day wait between issues in which the plotting is more suited to a daily soap opera causes me to forget what happened before, and I lose the thread of the story entirely. This is intentional, I’m sure. Comics publishers want buyers to pick up the individual issues to stuff in bags and collect, and save reading for the trade paper edition, which they think we’ll also buy. Stupidly, a lot of us do buy each issue and the collected edition that comes out within days after the final issue of a story arc. Indeed, sometimes the trade beats the final issue to the stands.

I’ve made no secret of the fact that I’m not much of a fan of modern comics. I don’t like the pace of the storytelling, where everything is so obviously plotted to fill a six-or-twelve-issue trade. Often nothing significant happens in a single month’s issue, and even more often, the thirty-day wait between issues in which the plotting is more suited to a daily soap opera causes me to forget what happened before, and I lose the thread of the story entirely. This is intentional, I’m sure. Comics publishers want buyers to pick up the individual issues to stuff in bags and collect, and save reading for the trade paper edition, which they think we’ll also buy. Stupidly, a lot of us do buy each issue and the collected edition that comes out within days after the final issue of a story arc. Indeed, sometimes the trade beats the final issue to the stands.