I received a copy of Heinlein’s Friday as a Christmas gift my senior year in high school. It had been out since the previous April, but I guess I wasn’t yet a rabid enough Heinlein fan to have picked it up the day it came out. Friday was, I believe, the book that changed me into that rabid fan.

I received a copy of Heinlein’s Friday as a Christmas gift my senior year in high school. It had been out since the previous April, but I guess I wasn’t yet a rabid enough Heinlein fan to have picked it up the day it came out. Friday was, I believe, the book that changed me into that rabid fan.

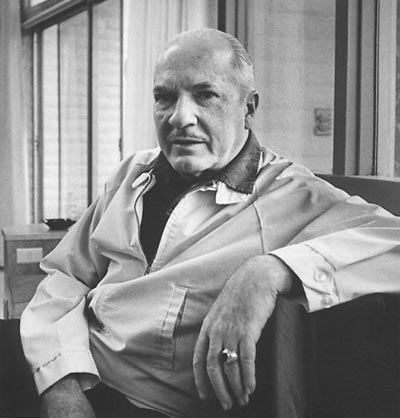

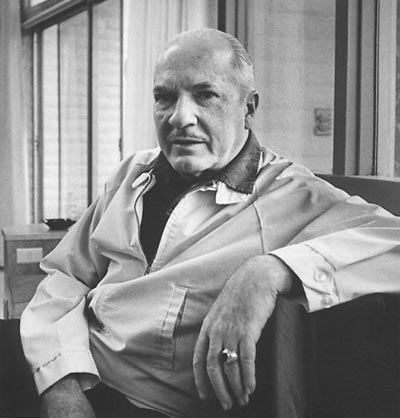

It was hailed as Heinlein’s return to his former glory. On the book jacket of the hardcover edition, Harlan Ellison said “Friday is Heinlein back in control.” I’ve never polled readers to ask if they agree with this assessment, but the sentiment is understandable. Friday represents a marked change in tone from Heinlein’s previous “adult” novels. By “adult” I don’t mean Heinlein was writing porn, though there are some detractors who would make that claim. After establishing himself in the 1940s as the King of John W. Campbell’s Astounding Science Fiction magazine, amongst other short fiction venues, Heinlein spent the 1950s as the reigning champion of juvenile (what we now call Young Adult) science fiction novels for Scribner’s. He wrote fourteen of these, although two, Podkayne of Mars and Starship Troopers, were rejected by Scribner’s juvenile editor, Alice Dalgliesh, and published subsequently by G.P. Putnam.

It wasn’t until these two rejected juveniles were released that Heinlein really came to be considered an author of “adult” science fiction novels. (Tuck away in the box where you store your little ironies that Heinlein’s juveniles are perfectly respectable adult science fiction stories. They just don’t speak plainly about sex. Heinlein consider this the only difference between juvenile and adult literature. Sixty years later, his juveniles are all still in print, and, I believe, none has ever gone out of print. Not many juvenile authors can make such a claim.)

I would never call Heinlein’s work formulaic. His imagination was such that, even were he to have written every book to a strict formula (and he didn’t), each would still represent an astonishingly unique and refreshing work due to the ideas draped on the frame of the formula. That said, most of his dozen Scribner books share a similar theme, that of a young man finding success and his place in the universe by means of tenacity, intellect and a good understanding of technology; Horatio Alger in space, if you will. Starship Troopers also carries this theme, but is extremely dark and militaristic. I’ve read it once, and recognize it as a competent piece of writing and deserving of attention. I will not read it twice, however. It represents one of the few times that Heinlein created a world I would not wish to visit.

Podkayne of Mars took a sharp turn away from this pattern by featuring a (gasp!) young woman as its protagonist. Narrated by Podkayne herself, it does have quite a different feel than its predecessor novels. In addition, in the original draft, Podkayne dies at the end of the story.

From here, Heinlein essentially abandoned the “boy meets world(s)” theme. Puppet Masters depicts spies handling an alien invasion; Double Star tells of an actor who must impersonate a head of state; Stranger in a Strange Land turns the “boy in space” idea on its ear, by bringing a human boy raised as a Martian to Earth; Glory Road is couched as a fantasy story, its hero not anyone you would call “boy;” Farnham’s Freehold catapults some members of Country Club Suburbia into a post-nuclear dystopia; The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is the story of a war of independence waged by a lunar colony against Earth. Time Enough for Love is the memoir of a millennia-old man who first appeared in Methuselah’s Children, where he led the escape of his fellow long-lifers from Earth; In I Will Fear No Evil, an old man’s brain is place in the body of a young woman, and, finally, in Number of the Beast, four geniuses narrate the story of their flight from earth as agents unknown try to assassinate them, and their subsequent escape into a nigh-infinite multiverse.

From here, Heinlein essentially abandoned the “boy meets world(s)” theme. Puppet Masters depicts spies handling an alien invasion; Double Star tells of an actor who must impersonate a head of state; Stranger in a Strange Land turns the “boy in space” idea on its ear, by bringing a human boy raised as a Martian to Earth; Glory Road is couched as a fantasy story, its hero not anyone you would call “boy;” Farnham’s Freehold catapults some members of Country Club Suburbia into a post-nuclear dystopia; The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is the story of a war of independence waged by a lunar colony against Earth. Time Enough for Love is the memoir of a millennia-old man who first appeared in Methuselah’s Children, where he led the escape of his fellow long-lifers from Earth; In I Will Fear No Evil, an old man’s brain is place in the body of a young woman, and, finally, in Number of the Beast, four geniuses narrate the story of their flight from earth as agents unknown try to assassinate them, and their subsequent escape into a nigh-infinite multiverse.

These last two efforts were poorly received by critics and many readers. Number of the Beast, in particular, is held up even today as strong evidence that Heinlein eventually lost his talent and possibly his mind, and that his work became hopelessly self-indulgent. News flash: All writing is self-indulgent. Authors write either for themselves or their editors. While in the latter case, it helps to first have the ego surgically removed, one indulges one’s editor only to fill one’s wallet. The end result is still self-indulgent.

Personally, I loved Number of the Beast. It was the first of Heinlein’s “adult” novels that I read, and I found myself dropping into the company of the Carter-Burroughs clan as comfortably as one drops into one’s favorite bathrobe. True, the novel does not have a tight, coherent plot. What it does have is witty dialogue and memorable characters who at least made me want to spend more time in their presence. In addition, there were some character beats included which made this then-sixteen-year-old misfit realize that perhaps it was okay for him to be exactly who he was, with no apologies to anyone.

If tight plotting and an odyssey of self-discovery were what readers wanted, however, Friday did represent a “return” to the Heinlein they remembered from decades passed. Although it lacks a male protagonist – Friday is a genetically engineered female with enhanced reflexes, intellect and strength – it does tell the tale of a young person navigating a strange and wondrous, sometimes hostile future, eventually stumbling over her destiny among the stars. Like Thorby in Citizen of the Galaxy, Friday is an outcast. “Artificial Persons” (APs) are not considered human by the unwashed masses. “My mother was a test tube, my father was a knife,” is their shared phrase of self-identification. They have no citizenship, no heritage, no party loyalties. Indeed, it’s legal for them to be owned by “real” humans. Friday, a trained combat courier working for a mysterious tactician known only as “Boss,” must hide her true nature from nearly everyone she meets.

Like the heroes of Have Space Suit Will Travel and Between Planets, she covers a lot of geography and is introduced to the alien world that is a space ship, a small foreign culture unto itself. Like all of Heinlein’s travelers, she winds up frequently down on her luck, stranded with few resources, and aided by kind-hearted strangers who ask only that she pay their kindness forward by way of recompense. And of course she has a mentor, an older man who, while gruff and demanding, nonetheless has her best interests at heart. Mr. Miyagi-like, Boss sets her to baffling tasks, the relevance of which she learns only long after she has undertaken them. Ultimately, she succeeds by being clever and resourceful, by learning to look past the face value of things, and by making friends she can count on. In Heinlein’s world, this makes her firmly “one of the boys.”

Like the heroes of Have Space Suit Will Travel and Between Planets, she covers a lot of geography and is introduced to the alien world that is a space ship, a small foreign culture unto itself. Like all of Heinlein’s travelers, she winds up frequently down on her luck, stranded with few resources, and aided by kind-hearted strangers who ask only that she pay their kindness forward by way of recompense. And of course she has a mentor, an older man who, while gruff and demanding, nonetheless has her best interests at heart. Mr. Miyagi-like, Boss sets her to baffling tasks, the relevance of which she learns only long after she has undertaken them. Ultimately, she succeeds by being clever and resourceful, by learning to look past the face value of things, and by making friends she can count on. In Heinlein’s world, this makes her firmly “one of the boys.”

And yet she is very female. Many critics have alleged that Heinlein’s women are all just wish-fulfillment constructs, representing what the author wished women were really like. Friday, however, is competent – more competent than any of the men she goes up against in the book. She has dalliances with several men (and a few women), but is not, despite the name, any man’s “gal Friday.” This is one of only four works of science fiction in which Heinlein used a female narrator to tell the story, the others being the aforementioned “Podkayne” and Number of the Beast, as well as his final novel, To Sail Beyond the Sunset. While I am not female, at no time during many readings of this novel have I ever felt pulled out of the story with a sense of “this is a dude writing the way he thinks a woman would write!” I should point out as well that Heinlein’s wife Ginny was, apparently, also his ideal of what a woman should be, and she was known to friends and acquaintances as supremely competent. Indeed, when the couple met, she was Heinlein’s superior officer in the Navy. A woman who fulfilled the wishes of Robert Heinlein would likely not be an empty-headed, big-chested chippie.

Unlike Heinlein’s boys, Friday is frankly sexual, and her story allows close examination of sexual customs and some possible future marriage scenarios. At the story’s opening, she is married into a group with seven husbands and co-wives. This New Zealand-based family is a business in which adult members buy shares. Its Chief Financial Officer, Anita, at first reminds a Heinlein reader of the no-nonsense Mum in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. Both rule their roosts and have a silent, strong influence over their co-wives and their husbands. Both seem unflappable. Both do grandmotherly things like sitting by the fire knitting. But Anita has a dark side and an obsession with money that Mum, a colonist deportee, could not conceive. When Friday has a falling out and parts with Anita’s family, all semblance of moral rectitude vanishes. The event is ugly and painful. As much as he described marriages, Heinlein didn’t deal often with divorce. That may be a result of the fact that he’d been through divorces himself, and chose to wait for time and perspective before he addressed the issue in his work. When he does relate a story of divorce, however, he does so with tremendous emotional power.

Friday is next welcomed into the home of a woman with two husbands. She bonds with this woman, Janet, as the mother she never had. Again, this is a departure from the young Odysseus theme. Though Odysseus was always seeking his home, he was not looking for anyone with whom to form an emotional attachment. The boys in the juveniles similarly were not. While many wound up in love or married, seeking companionship or family ties was not the primary business of any of them.

If you want to introduce readers of mainstream thrillers, be they readers of Dan Brown, John Grisham or Ian Fleming, to science fiction, Friday is an excellent jumping-off point. I know from my days in libraries that non-SF fans who “had” to read a science fiction book were extremely pleased when I placed this one in their hands, and would make a point of coming back to tell me so. One strong objection some have to the book – that being Friday’s treatment of a man who rapes her – I will not address. The theme is a complex one, and will serve to provide the topic for a future column.

Oh, lest I forget, this is another old favorite I listened to over the past couple of weeks. I’ve long had a two-cassette abridged reading by Samantha Eggar. She did quite a creditable job, but this is a book which deserves to be heard in its entirety. Hillary Huber’s unabridged reading for Blackstone Audio was very enjoyable. Ms. Huber has terrific range for character voices, and a vocal quality much like that of Peri Gilpin of Frasier. After hearing her reading, it did occur to me that Friday, being Baltimore-born and raised, would probably not have Ms. Eggar’s delightful accent. Still, if you have a chance to pick up that abridgement, by Listen For Pleasure from back in the eighties, it’s fun.

I received a copy of Heinlein’s Friday as a Christmas gift my senior year in high school. It had been out since the previous April, but I guess I wasn’t yet a rabid enough Heinlein fan to have picked it up the day it came out. Friday was, I believe, the book that changed me into that rabid fan.

I received a copy of Heinlein’s Friday as a Christmas gift my senior year in high school. It had been out since the previous April, but I guess I wasn’t yet a rabid enough Heinlein fan to have picked it up the day it came out. Friday was, I believe, the book that changed me into that rabid fan. From here, Heinlein essentially abandoned the “boy meets world(s)” theme. Puppet Masters depicts spies handling an alien invasion; Double Star tells of an actor who must impersonate a head of state; Stranger in a Strange Land turns the “boy in space” idea on its ear, by bringing a human boy raised as a Martian to Earth; Glory Road is couched as a fantasy story, its hero not anyone you would call “boy;” Farnham’s Freehold catapults some members of Country Club Suburbia into a post-nuclear dystopia; The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is the story of a war of independence waged by a lunar colony against Earth. Time Enough for Love is the memoir of a millennia-old man who first appeared in Methuselah’s Children, where he led the escape of his fellow long-lifers from Earth; In I Will Fear No Evil, an old man’s brain is place in the body of a young woman, and, finally, in Number of the Beast, four geniuses narrate the story of their flight from earth as agents unknown try to assassinate them, and their subsequent escape into a nigh-infinite multiverse.

From here, Heinlein essentially abandoned the “boy meets world(s)” theme. Puppet Masters depicts spies handling an alien invasion; Double Star tells of an actor who must impersonate a head of state; Stranger in a Strange Land turns the “boy in space” idea on its ear, by bringing a human boy raised as a Martian to Earth; Glory Road is couched as a fantasy story, its hero not anyone you would call “boy;” Farnham’s Freehold catapults some members of Country Club Suburbia into a post-nuclear dystopia; The Moon is a Harsh Mistress is the story of a war of independence waged by a lunar colony against Earth. Time Enough for Love is the memoir of a millennia-old man who first appeared in Methuselah’s Children, where he led the escape of his fellow long-lifers from Earth; In I Will Fear No Evil, an old man’s brain is place in the body of a young woman, and, finally, in Number of the Beast, four geniuses narrate the story of their flight from earth as agents unknown try to assassinate them, and their subsequent escape into a nigh-infinite multiverse. Like the heroes of Have Space Suit Will Travel and Between Planets, she covers a lot of geography and is introduced to the alien world that is a space ship, a small foreign culture unto itself. Like all of Heinlein’s travelers, she winds up frequently down on her luck, stranded with few resources, and aided by kind-hearted strangers who ask only that she pay their kindness forward by way of recompense. And of course she has a mentor, an older man who, while gruff and demanding, nonetheless has her best interests at heart. Mr. Miyagi-like, Boss sets her to baffling tasks, the relevance of which she learns only long after she has undertaken them. Ultimately, she succeeds by being clever and resourceful, by learning to look past the face value of things, and by making friends she can count on. In Heinlein’s world, this makes her firmly “one of the boys.”

Like the heroes of Have Space Suit Will Travel and Between Planets, she covers a lot of geography and is introduced to the alien world that is a space ship, a small foreign culture unto itself. Like all of Heinlein’s travelers, she winds up frequently down on her luck, stranded with few resources, and aided by kind-hearted strangers who ask only that she pay their kindness forward by way of recompense. And of course she has a mentor, an older man who, while gruff and demanding, nonetheless has her best interests at heart. Mr. Miyagi-like, Boss sets her to baffling tasks, the relevance of which she learns only long after she has undertaken them. Ultimately, she succeeds by being clever and resourceful, by learning to look past the face value of things, and by making friends she can count on. In Heinlein’s world, this makes her firmly “one of the boys.”

Resentment of the immortal has been a common theme in fictional works which addressed immortality. In Heinlein’s

Resentment of the immortal has been a common theme in fictional works which addressed immortality. In Heinlein’s  But Tarzan and John Carter got to be immortal alongside their loved ones. They didn’t ever really have to reflect on what it was like to watch those they cared for age and die while they remained young and perfect. Nor did the comparatively young Lazarus Long in Methuselah’s Children. They were too busy hiding their immortality, running from those who coveted it, or just plain ignoring the short-lived.

But Tarzan and John Carter got to be immortal alongside their loved ones. They didn’t ever really have to reflect on what it was like to watch those they cared for age and die while they remained young and perfect. Nor did the comparatively young Lazarus Long in Methuselah’s Children. They were too busy hiding their immortality, running from those who coveted it, or just plain ignoring the short-lived. Isaac Asimov gave us a glimpse into the long-lifer-loves-short-lifer scenario from a dual perspective in

Isaac Asimov gave us a glimpse into the long-lifer-loves-short-lifer scenario from a dual perspective in  But an immortal character I wrote about last week, Max August, does have expectations that his dead loved one will return, and they seem sane because his creator deals with immortality on two levels. Max, an alchemist, is physically immortal as a result of his craft. He lost his wife, Valerie, years ago on New Year’s Eve; but Valerie is likewise immortal. She’s just not physically immortal, she’s spiritually immortal. For many All Hallows Eves, Valerie contacts Max to let him know she’s still there. As of Max’s latest adventure, The Plain Man, Max is expecting Val’s return in the flesh, and Val is… well, we’re not sure what Val is. We think she’s trying to come back, but the forces of evil are doing their damndest to stop her.

But an immortal character I wrote about last week, Max August, does have expectations that his dead loved one will return, and they seem sane because his creator deals with immortality on two levels. Max, an alchemist, is physically immortal as a result of his craft. He lost his wife, Valerie, years ago on New Year’s Eve; but Valerie is likewise immortal. She’s just not physically immortal, she’s spiritually immortal. For many All Hallows Eves, Valerie contacts Max to let him know she’s still there. As of Max’s latest adventure, The Plain Man, Max is expecting Val’s return in the flesh, and Val is… well, we’re not sure what Val is. We think she’s trying to come back, but the forces of evil are doing their damndest to stop her. I think, though, that our immortal companions, the fictional ones, the myths, serve a purpose even in this capacity. They can, if we let them, remind us that youth doesn’t have to go away, that the best in us doesn’t have to age. Indeed, it can go on forever. So even though we look at them differently from year to year, I think spending a little time with ageless childhood friends can be healthy. It allows us to, as Ellen Degeneres said in a stand up routine a few years ago, “play with our inner child.” She pointed out that, if we didn’t, our inner child could be just as spiteful and vindictive as any other child who’s being ignored.

I think, though, that our immortal companions, the fictional ones, the myths, serve a purpose even in this capacity. They can, if we let them, remind us that youth doesn’t have to go away, that the best in us doesn’t have to age. Indeed, it can go on forever. So even though we look at them differently from year to year, I think spending a little time with ageless childhood friends can be healthy. It allows us to, as Ellen Degeneres said in a stand up routine a few years ago, “play with our inner child.” She pointed out that, if we didn’t, our inner child could be just as spiteful and vindictive as any other child who’s being ignored.