A few times in years past, I’ve participated in discussion panels at local conventions on the topic of God in science fiction. More specifically “Is there room for god in Science Fiction?” (I’m being deliberately inconsistent in my capitalization of that sentence, because it depends on who you are as to which of the two topics is more deserving of reverence.) My answer? Of course there’s room for God in science fiction! There’s room in science fiction for

everything that can be speculated upon under the existing body of scientific law. Certainly, the existence of a being of advanced intelligence and power, who to us would appear both omnipotent and omniscient, is an appropriate topic.

The point of the question, of course, is that God is often not treated as an item of speculation. God is treated by many as a defined quantity, about whom everything is recorded in sacred literature. If those sacred texts defy what we think we’ve learned about the universe, then we’re wrong and those texts are right, even if they were written a thousand years ago by people who thought a flat earth was the center of the universe. Ironically, many atheists cling as stubbornly to this narrow definition of god as do fundamentalists.

I guess there’s no room for that god in science fiction. If you’ve read my science fiction, however, you know that I don’t believe in that god, and that I certainly think there’s room to discuss multiple definitions of god. My work is lousy with references to gods of all sorts. I’m fascinated by religion and mythology, even though I’m a rationalist and believe in the scientific method.

Karen Armstrong is a rationalist, too. A former Roman Catholic nun, she’s written quite a number of books on the histories of religions – Christianity, Islam, Judaism and Buddhism among them. I’ve studied a couple of her works in my scandalously liberal Methodist Sunday School class. I’m about convinced that Ms. Armstrong knows more about the human conception of God than I will ever know or God will ever tell me. Her books are long, scholarly, and sometimes daunting; but they’re worth your time, if you want to understand the very complex history of human religion.

But you’re probably saying “Hey, Steve, what’s all this got to do with your promise to point us at good SF? We want to find the next Moon is a Harsh Mistress, not take a college course from a lapsed nun! She might come at us with a ruler, and then where would we be? In a broken heap at the bottom of the stairs, like stunt doubles from The Blues Brothers! If we’re going to read a long book, it better have robots, computers, spaceships, time machines or at least babes in chain mail bikinis!”

Hang tight. First of all, Armstrong’s, A Short History of Myth is, as its name implies, not a long book. At 149 pages, hardbound and only five inches by eight, it looks like it should be part of your Winnie the Pooh collection, except that it has no stuffed bear on the cover, tubby or otherwise. It’s a brief outline of what Armstrong sees as the six ages of myth, beginning around 20,000 BCE and running up to the present day.

The bearing this has on speculative fiction was admirably summed up in the much-maligned film Star Trek the Motion Picture,* wherein the artificial intelligence called Vger seeks its creator, hoping to answer the question, “Is this all that I am? Is there not more?” That is the purpose of myth: to look beyond the everyday, the factual, the mundane and find out what there is that we cannot see. This is transcendence. This is ecstasy. As Armstrong puts it:

“We seek out moments of ecstasy, when we feel deeply touched within and lifted momentarily beyond ourselves. At such times, it seems that we are living more intensely than usual, firing on all cylinders, and inhabiting the whole of our humanity.”

As can be inferred, “myth” means something more than a misconception such as Penn and Teller might debunk for us, or an overblown story which we like to believe, but is, in fact, false, like George Washington and the cherry tree. Myth, as related by Armstrong, is a story which informs us on how we are to behave, how to interact with others, how to make moral decisions. Myth sets an example for us in story or parable, and myth has direct bearing on our lives.

And this is an important point: Myth is not mean to be believed as fact or history. Pick up any volume of Greek myths, or a book of creation mythology, and the jacket will tell you that ancient peoples created myths in order to explain how the world came to be. This suggests that myths served, for ancient civilizations, the same purpose as Kipling’s Just So Stories. That is, they gave a whimsical explanation for how something that exists now developed in the way it did. Armstrong disagrees with this definition. Myth, she says, was not used by the ancients to entertain or to answer questions about history; it was meant to give people a moral framework and show them how the divine (a great world which exists beyond this one) was reflected in their everyday lives.

For the Greeks, greatest of the mythologists, there were two systems of thought, mythos and logos. Logos was the “logical, pragmatic and scientific mode,” and mythos the moral, the spiritual. Plato and Aristotle both disliked mythological thinking, because it made no sense in a rational context. It was all about emotion. In order to be understood, the listener or reader had to be caught up in the feelings produced by the story being told in, say, a tragedy by Sophocles. Armstrong is quick to point out that we should not share Plato and Aristotle’s impatience with mythos. We’re incomplete without it, she says, and not just because we lack religion. Indeed, she sees that religion doesn’t work for many people today:

“Religion has been one of the most traditional ways of attaining ecstasy, but if people no longer find it in temples, synagogues, churches or mosques, they look for it elsewhere: in art, music, poetry, rock, dancing, drugs, sex or sport. Like poetry and music, mythology should awaken us to rapture, even in the face of death and the despair we may feel at the prospect of annihilation. If a myth ceases to do that, it has died and outlived its usefulness.”

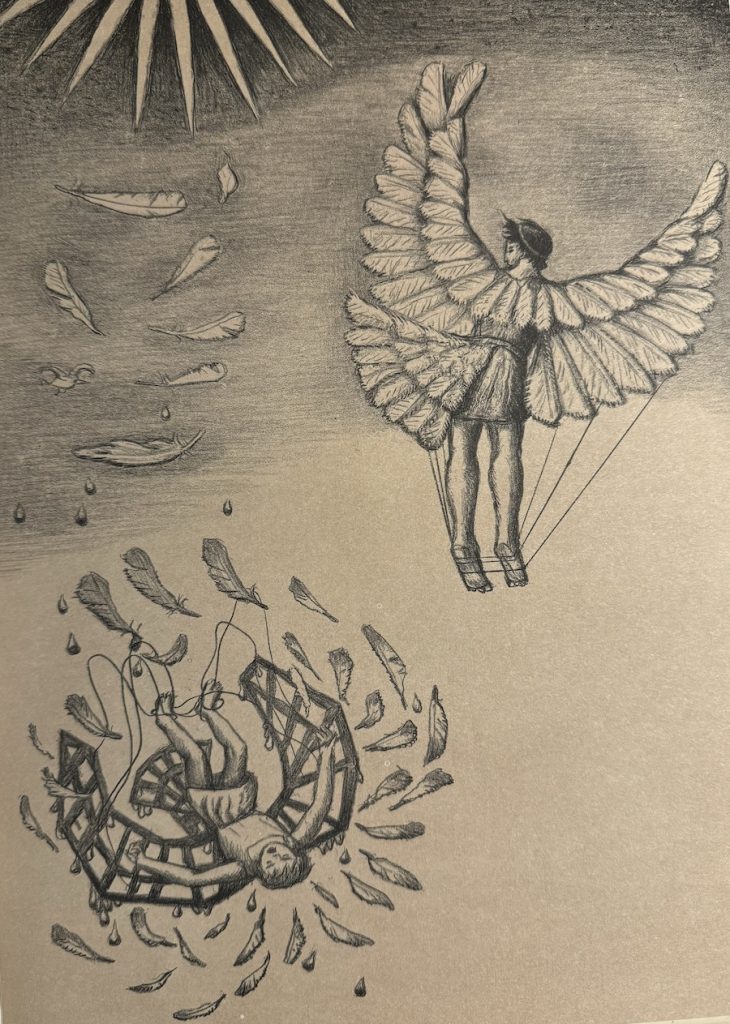

It’s almost as if she’s saying, countering the fundamentalists, that it’s not our fault as humans that we’ve moved away from God. It’s the fact that God has become irrelevant to us that has caused us to move away. If myths are to inform our moral choices, then myths need to hit us where we live. And we don’t live in the age when a micro-managing god summoned his prophet to the mount to tell him that the people shouldn’t eat seafood. Fundamentalists miss the point. The stories they claim are history and science were never intended to be either. They were intended to make us feel, to set us an example, and they were intended to change as our needs changed. Zeus evolved in Greece from being a distant sky god to being a randy traveler among us, searching out our prettiest girls, and occasionally boys. This happened because a distant sky god wasn’t much use to anyone. Indeed, Uranus, Zeus’s grandfather, was castrated and thrown out of power because he was a distant sky god, and couldn’t be interacted with, even in parable. Uranus was a first draft of the sky god, and it took a few tries to get him right. For the ancients, gods, like people, evolved.

But, Armstrong notes, mythology essentially stopped evolving in the Axial Age, around 200 BCE. Today our spiritual lives are still informed by the Hebrew Prophets, by Plato and Aristotle, by Confucius, Buddha and Laozi. All progress has been on the rational side. “Western modernity,” she says, “was the child of logos.” Fundamentalism grew from the frustration felt by some of those who still wanted spiritualism, who found the purely rational here and now too limiting, who asked, “Is this all that I am? Is there not more?” and came up with an answer that was, in itself, limiting; because they tried to force the spiritual into the framework of the rational. They tried to insist that myth was fact.

Others, as Armstrong relates, found other ways to fill the spiritual vacuum.

“We still long to ‘get beyond’ our immediate circumstances, and to enter a ‘full time,’ a more intense, fulfilling existence. We try to enter this dimension by means of art, rock music, drugs or by entering the larger-than-life perspective of film. We still seek heroes. Elvis Presley and Princess Diana were both made into mythical beings, even objects of religious cult. But there is something unbalanced about this adulation. The myth of the hero was not intended to provide us with icons to admire, but was designed to tap into the vein of heroism within ourselves. Myths must lead us to imitation or participation, not passive contemplation. We no longer know how to manage our mythical lives in a way that is spiritually challenging and transformative.”

Indeed, I’d have to agree with Armstrong that a lot of our secular answers to these needs ring hollow. For years, I’ve been dissatisfied with the modern definitions of heroism, such as this one from Arthur Ashe: “True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is not the urge to surpass all others at whatever cost, but the urge to serve others at whatever cost.” I’ve always known I disliked the definition, all due respect to Mr. Ashe and his accomplishments. I knew that the heroes of my mythology didn’t do anything as pedestrian as sublimating their identities and just serving others. James T. Kirk would have (and did, if you believe his lesser mythologists) died saving the universe. George Bailey would have died to save his brother Harry or any of his family. Lazarus Long did die (kind of) to win the approval of his beloved Mama Maureen. But none of these heroes ever, for a minute abandoned their identities or forgot their own needs, even if they did sometimes give priority to some goal other than their immediate safety or personal ambition.

What troubled me was that I couldn’t write a personal definition of heroism which emotionally satisfied me. I came up with this:

A hero is someone who puts his principles ahead of all else, including personal convenience, comfort and safety.

That seemed to be a definition of heroism that was less prone to manipulation by draft boards or charities that sink so low as to employ telemarketers. (For the fate of both of these entities, see Shepherd Book’s sermons on “the special hell.”)

Ms. Armstrong’s book has allowed me to come up with this definition, which I like a lot better:

A hero is someone who acts when others are unwilling to do so, and whose actions inspire us also to act in ways that change our surroundings for the better.

And here, I think, is the place where science fiction and fantasy intersects mythology, as mythology has always been intended to serve. Fantastic literature is particularly suited to describing the extraordinary. There is everyday heroism, of course; but most of us are a bit thick, and it’s easier to get the point across to us if you’re not subtle. Everyday heroism is subtle. The heroism of our science fiction stories, our television shows, our movies and our comic books is not. And so it reaches more easily into our lives and makes itself relevant to us.

Armstrong summarizes, near the end, the downside of centuries of devotion to pure reason: “…during the twentieth century, we saw some very destructive modern myths, which have ended in massacre and genocide… We cannot counter these bad myths with reason alone, because undiluted logos cannot deal with such deep-rooted, unexorcised fears, desires and neuroses.”

I would qualify this statement. As demonstrated by Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, rational analysis certainly can help us navigate the morass of emotions which sometimes cause us anxiety and pain. A lot of the problems that overwhelm us day in and day out can be solved if we take a breath and think our way through them, instead of oozing emotion all over everyone. I think Armstrong’s point, though, is that cold, rational truth is not enough. We need an emotional framework in which to function. We need inspiration. We need to occasionally ask, as cliched as it sounds, what our heroes would do in a given situation, whether our hero is Jesus, the Dalai Llama or John Galt. (And yes, I believe there is the power of myth even in works of fiction created to appeal to the rational mind, as is Atlas Shrugged. Ayn Rand made it clear that her heroes were not men as they are everyday, but men as they should be. That is a valid definition for a myth, and I believe she created one that has power for a lot of people.)

And with that last I pointed at the conclusion which I drew while reading Armstrong’s book, and which I was happy to see she drew as well: Our new mythology is not the province of traditional religion any longer. It is the province of our novelists, our storytellers, our movie makers and our playwrights. Robert Heinlein saw this thirty years ago when he explored the concept of the World as Myth. His characters, beginning in The Number of the Beast, learned that there were a nigh-infinite number of universes in which the fictional realities postulated by the most powerful storytellers were brought into being by sheer creative energy. Andrew M. Greeley also played with this in God Game. I recommend both works.

But it’s important that our new mythologists remember that their job is not only to entertain or to explain. It’s to motivate, to inspire, to take us beyond the everyday and the pedestrian. To show us how our lives are a reflection of the world beyond, whatever that is. This is not all that you are. There is more.

It’s not a purely rational idea, no. And don’t think I’m advocating that we abandon reason and surrender to unbridled passion (though we should probably all do that sometimes.) Like Karen Armstrong, I’m saying that we need to spend at least part of our time thinking and talking about how things should be, in addition to how they are. That way, when it’s time to go out and do something, we have a road map.

* A story coincidentally developed by Alan Dean Foster, who I featured last week. In a reversal of his usual practice, Foster developed the plot for the film, and series creator Gene Roddenberry wrote the novelization.

This is a mood piece. I was in a mood when I wrote it. But the critic raved, so I was motivated to share…

This is a mood piece. I was in a mood when I wrote it. But the critic raved, so I was motivated to share…