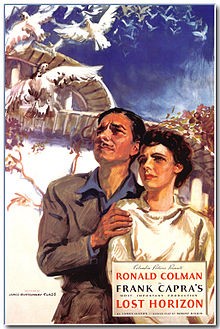

I’ve written about Lost Horizon before. The 1937 film is one of my favorite movies. Recently, more than one person has commented to me that they love the film too, and then they’ve ruminated on how adorably dashing Michael York was in the 1970s.

I’ve written about Lost Horizon before. The 1937 film is one of my favorite movies. Recently, more than one person has commented to me that they love the film too, and then they’ve ruminated on how adorably dashing Michael York was in the 1970s.

Well, agreed, Michael York was adorably dashing in the 1970s. But Michael York, who was born in 1942, was understandably not involved in the 1937 Frank Capra adaptation of James Hilton’s bestseller, Lost Horizon. A lot of people my age were first exposed to the story as a result of Ross Hunter’s lamentable remake in 1973. That version of the film was a musical, which songs by the legendary Burt Bacharach. This film contributed little to his legend. Interestingly, though, the people my age who saw it—most likely its mid-70s TV airing on NBC’s The Big Event—seem to share the experience of not only thinking they saw the original, but of utterly (and thankfully) forgetting that the picture was a musical. I include myself in that number. I had no idea I had not seen Capra’s version until I saw Capra’s version. To be fair, the 1973 film is virtually a shot-by-shot remake of the original until the kidnapped party’s plane crashed in the Himalayas. No one sings until the party arrives at Shangri La, the lamasery in the hidden Valley of the Blue Moon, where the snows never fall, the chill mountain winds do not blow, and human beings live centuries without aging. (If you are a fan of the musical, take heart in the fact that I not only own the soundtrack album, I’ve actually listened to it.)