“To Serve and Obey, And Guard Men from Harm.”

That’s their slogan. They’re the humanoids, created by a well-intentioned scientist named Warren Mansfield – or was it Sledge? – on the distant planet Wing IV. In a more pedestrian sense, they were created in the mind of Jack Williamson in 1947. For all our sakes, it would be best to hope they stayed confined to the imagination of the late, great Jack Williamson. Sadly, his inspiration for them was all too real.

Before I delve into the novel, a personal note: I owe Jack Williamson a debt. With three words, he jump-started my writing career. Not “career” in the sense of making money. I’m talking about having a career in the sense that you accept that something is your life’s work, and you do that work, no matter the compensation or the reception of it by others. I’d already made money at writing when I very briefly met Mr. Williamson at a Writers of the Future banquet in the 1990s. (No, I’ve never won the WotF competition. I was there only through the generosity of Dr. Yoji Kondo, a dear friend who has always encouraged me to keep writing science fiction.)

The three words? “Shame on you!” Why did he say them? Because I’d already told him I was “trying to be” a writer, and that I’d sold a few stories to DC Comics. After remarking on his friendship with the legendary Julie Schwarz, the aged and frail Williamson asked me what I was writing at the time. I told him nothing, because I didn’t have any connections and didn’t have a market. And that’s when he shook his finger at me and said “Shame on you!”

Imagine if you will the impact of this, coming from the Dean of Science Fiction (the second one, after the death of Robert A. Heinlein) on a young fan and writer. He wasn’t mean about it. He was smiling and speaking very gently. But he explained to me that I should be writing all the time, connections or no connections, sales or no sales, markets or no markets. I went home that night and roughed out the novella “Capital Injustices,” which has been podcast on audio, and will eventually be released in a short fiction collection I keep putting off. I offered it to six or seven markets which all passed on it. But once Jack’s shaking finger started me writing, I’ve never stopped. Fifteen or so years later, I’m not rich from writing and I’ve never sold another story to a publisher in New York, but I’m still writing, and I’ve managed to find readers and listeners despite the odds. I’d like to think Jack would no longer shake his finger at me, were he here.

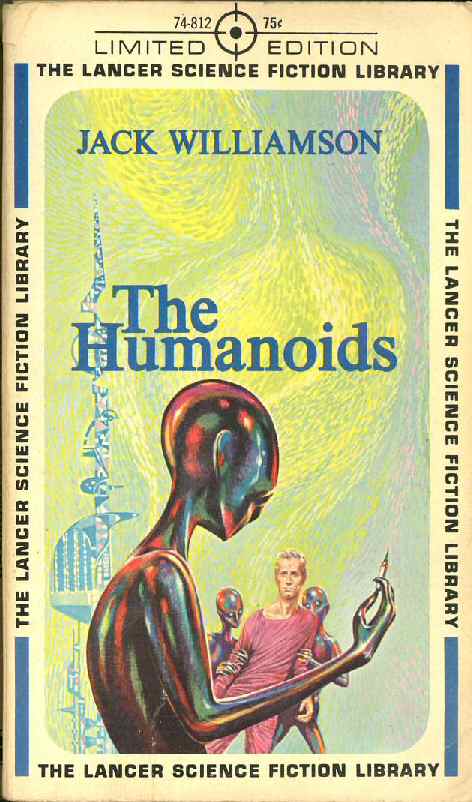

On to what’s been called his greatest novel, one of roughly fifty that he wrote. The Humanoids began life as the novella, “With Folded Hands.” This first version is included in many mass market editions of the novel. In that short piece, a man named Underhill, a dealer in “mechanicals” – crude robots designed to perform household chores – encounters in the same day a new business called “The Humanoid Institute” and a down-on-his-luck scientist who turns out to be the inventor of the advanced robots which the Institute is distributing. It’s important to note that the Institute is not “selling” humanoids. It’s giving them away. Its representative, a humanoid itself, tells Underhill that he will quickly be out of business because his business is no longer needed.

The humanoids were created on Wing IV, a planet unknown to Underhill, and which is discussed little in the text. It’s presumably a human colony, for Sledge, the inventor of the humanoids, comes from there and is as human as anyone on earth. Sledge is the discoverer of the science of rhodomagnetics, a force which brought about a war on Wing IV and obliterated its human population. Hoping to right his wrong, Sledge builds the humanoids to serve humanity. The mechanicals serve us right into oblivion, putting us out of business, taking over our homes, letting us take no risks, telling us what to eat and what not to eat. Humans become cherished slaves. Underhill and Sledge attempt to defeat their oppressors, to no avail. Their efforts are thwarted, and Sledge is “cured” of his “delusion” of being the humanoids’ creator by brain surgery – surgery to remove a dangerous tumor, of course.

Williamson said in an interview that he based this story partially on childhood anxieties about being too closely supervised by the adults in his family and partially on the unease he (and many others) felt at the use of nuclear weapons on Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of World War II. He saw technology which was created with the best intentions (though some might debate the good intentions behind the development of nukes) overtaking the ability of humanity to control it, and possibly leading to our destruction.

The story may have been a trend-setter, actually; and as is often the case, those who followed the trend had neither the subtlety nor the imagination of the person who set the trend. A plethora of science fiction B-movies in the 1950s took as their theme the dangers of technology. In addition to Williamson’s Humanoids, and “With Folded Hands,” they were the step-children of Frankenstein and of the dawn of the nuclear age. These works, by and large, were preachy and heavy handed, warning us over and over that technology was bad. Unlike Williamson, they didn’t leave us thinking, “I’d better be careful,” they shook that finger in our face (that finger which I prefer to think Jack reserved for recalcitrant young writers) and said “be afraid. Be very afraid.”

Years later, these works are simply laughable. Williamson’s frightening tales of the humanoids, however, can still shake a thinking person to the core. We look at the killing kindness of these robots and we hear the pleas of their victims, not for freedom, but for more of their “service,” and we reflect how easily we might fall into a similar state of slavery. Our masters might not be sleek, little, black robots, but our world is filled with monsters enough who offer to fulfill our every whim if we’ll just give up our individuality.

Williamson expanded “With Folded Hands” into the novel The Humanoids, published in 1948. The setting is no longer earth, but a human colony in the distant future, one hundred centuries after Hiroshima. Warren Mansfield replaces Sledge as the humanoids’ creator, but is not nearly as much a part of the action of the story. Underhill’s part is taken by astronomer Clay Forester (yes, the same name as the scientist hero of War of the Worlds, both the 1953 and 2007 versions. It was also the name of a character in the TV series Rawhide. This is the kind of thing Philip Jose Farmer could have based a book upon!)

The novel describes a much more evolved conspiracy against humanoid domination, including a telekinetic child prodigy named Jane Carter and a charismatic leader named Mark White. As the humanoids are arriving on the planet (never named) which is home to Forester’s Starmont Observatory, White explains to the astronomer that 90 years ago, the planet Wing IV reached a technological crisis point, as every civilization does, as earth did, we presume, when it developed nuclear weapons. The only possible paths past such a crisis point are death and slavery, says White, but Warren Mansfield of Wing IV believed he had found a third alternative – the humanoids. These benevolent creatures would protect humans from all harm, not allowing them to go to war, to injure themselves or others. White makes it clear that this third possible outcome of a technological crisis is by far the worst.

Forester’s world is facing such a crisis as the men meet. A spy has returned to tell their government that the enemy, the TriPlanet Powers, has developed a mass conversion weapon which could wipe them out utterly. Forester doesn’t know what could be worse than that. White insists the humanoids are, indeed, a fate worse than death or simple slavery. He knows this from personal experience as a protégé of Warren Mansfield himself.

Williamson takes advantage of the novel’s greater scope to more greatly develop the horror of the nanny state imposed by the humanoids. When they arrive to offer to rescue Forester’s people from destruction by the TriPlanet Powers, offering that dreaded “third alternative,” control of a world is handed to them, not by the whim of each householder asking for a free manservant and getting a pig in a poke, but by the elected representative government of a world voting them into power, as some of the worst tyrants have been voted into power throughout history.

The humanoids’ aim, an expansion on their “Prime Directive” (truly, there are no original ideas!) sounds familiar, similar to the aims of so many well-intentioned groups in our history who have brought death, disaster and suffering to nations:

“…our only function is to promote human welfare. Once established, our service will remove all class distinctions, along with such other causes of unhappiness and pain as war and poverty and toil and crime. There will be no class of toilers, because there will be no toil.”

When he questions their authority, the humanoids are quick to remind Forester that “All necessary rights to set up and maintain our service were given us by a free election.”

Scary? Certainly. For more than a handful of readers would react to such statements by saying, “And what’s wrong with that?” Williamson goes on to illustrate what’s wrong. There’s a chilling scene in which Forester comes home to find his wife playing with blocks, babbling like an infant, having been given euphoride, a drug which “relieves the pain of needless memories and the tension of useless fear. Stopping all the corrosion of stress and effort, it triples the brief life expectancy of human beings.” Forester demands of his humanoid keepers if his wife asked to be cast into this oblivion, and is told it’s not up to the humans to ask. If the machines feel they need to be drugged into happiness, they will be drugged. There will be no discussion, no right of appeal. Throughout much of the book, Forrester lives with the constant threat of being given euphoride.

Forester’s observatory is torn down by the mechanicals, partly because they need the land for housing, something else which is assigned by them with no input from their human charges, and partly because science is, well dangerous. “We have found on many planets that knowledge of any kind seldom makes men happy, and that scientific knowledge is often used for destruction.”

Too often in my life I’ve heard people with the best, gentlest intentions say, “I think there are some things we have a right not to know…”

Indeed, in the humanoids’ world, humans are not even allowed the danger of solitude. When Forester asks to be allowed to go for a simple walk, he’s refused: “Our service exists to guard every man from every possible injury, at every instant.”

The longer version of the story allows our rebels to travel to the home world of the humanoids and discover the cybernetic brain which controls all – and remember this tale came fifty years before Jean Luc Picard raided the Borg homeworld. We also encounter disturbingly personable and persuasive humanoid sympathizers like Frank Ironsmith, the most popular guy in Clay’s lab, set up at the outset as his rival.

Overall, the story is chilling, complex and conveys a certain ambiguity about where we, humanity, go from here, the brink of our destruction by our own technology. Never does Williamson preach, despite sculpting such a rich reality from the simple premise that the road to hell is paved with good intentions. I read this as a high school student, or possibly as a college freshman. It holds up well. If anything, I appreciate it more in my forties than I did as a teen. I may sometime dig into his sequel, The Humanoid Touch, but I make it a rule never to read two books by the same author back to back.

As I did with Orphan Star, I listened to this one. I prefer to save reading time for books I’ve not read before, as I’m not the most careful of listeners. It’s read by the same voice actor, Stefan Rudnicki. He’s an excellent narrator and good with distinguishing voices, though I have to say the Brooklynesque voice he chose for Jane Carter began to wear on me after a while. One can only here “Mistah White Sez” so many times without wanting to throttle a child who isn’t even there. But SF child prodigies aren’t often the most endearing creatures.

The excellent radio series Dimension X also adapted the short, “With Folded Hands.” It’s available for your listening pleasure here.