Lionel Barrymore is probably best remembered as Mr. Potter by today’s audiences. That’s too bad, in some ways, as that means a lot of people don’t know that Potter is despicable, not because Barrymore was despicable, but because Barrymore was such a great actor. Watch him in You Can’t Take it With You or Grand Hotel, both Oscar winners from the 1930s, and you’ll find it hard to believe you could ever hate this man in any role he played. But you can and do hate Henry F. Potter. The only sympathy he might evoke stems from the fact that he’s in a wheelchair. But, aside from the imperious way he commands his goon (Yep. That’s his name in the screenplay: Goon.) to wheel him around, that’s a detail you barely notice. This man is evil. (And Potter is in a wheelchair, I believe, only because Barrymore himself was confined to a wheelchair by arthritis aggravated by an accidental break of his hip at age 60.) Barrymore had excellent practice for playing a greedy Christmas film villain: he performed 19 times as Ebenezer Scrooge in the annual Christmas Day broadcasts of A Christmas Carol begun in 1934 by CBS and Campbell’s Soups.

But is Henry F. Potter, who, unlike Scrooge, is never redeemed, too much of a caricature? Indeed, in a country in which the politics of envy seem to be fueling an ever-greater hatred of financial success, is he actually a dangerous stereotype? Like Chris Cooper’s character in The Muppets, he could be taken as the producers’ way of saying that all industrialists and financiers are inherently evil (unless, of course, they’re spending their money making movies.) Henry Potter could be taken as an indictment of Capitalism. It’s for that very reason that many libertarians and Objectivists despise this film.

But I don’t see Mr. Potter as a caricature. I see him as an illustration of a very specific kind of person who really exists, who was with us in the 1930s and 1940s, who is with us still, and who, yes, manages to thrive when all around him are miserable. Henry F. Potter is a Crony Capitalist, or, as the great L. Neil Smith dubs them, a Rotarian Socialist.

In his introductory scene in the film, Mr. Potter is seen arguing with Peter Bailey, the father of our protagonist, George, who is, at the time, about twelve years old. Bailey is making a plea for thirty more days to repay a loan Potter has given him. Bailey owns a Building & Loan, a private cooperative of a type which became prevalent in the mid 1800s. Working class people wanted to buy houses, but banks were operated by the wealthy for the convenience of the wealthy, and did not lend money to those who didn’t have the collateral to secure the loan. Mortgages, as they exist today, were unheard of. In fact, the first mortgages were made by insurance companies, not banks, and payments did not reduce the amount owed, they merely collected the interest due. So Savings and Loan Associations, as they came to be called after FDR began subsidizing them with taxpayer dollars in the 1930s, pooled the limited funds of middle class customers and use them to provide home loans.

Potter makes several of his attitudes apparent in this first scene. For one, he detests begging, which he thinks Bailey is doing on behalf of his clients. Bailey believes he’s enabling the American Dream, something he makes clear in a statement to George in later years: “I feel that in a small way we are doing something important. Satisfying a fundamental urge. It’s deep in the race for a man to want his own roof and walls and fireplace, and we’re helping him get those things in our shabby little office.”

Keep in mind that the societies from which America tore itself away in the 1700s did not have a strong history of upward mobility. If you were born a serf on the estate, you belonged to the estate. You owed your service and loyalty to its owner, and, in return, he provided you with a place to live, and let you keep some of the fruits of your labors. At Christmas, he probably gave you a ham. This tradition of noblesse oblige is celebrated to an extent in A Christmas Carol. But the dark side of noblesse oblige is that, in return for his obligations to give you food and housing and a Christmas ham (and, dare I say it, Health Care?), the Lord of the Manor had control of your life to a large degree. The Lord of the Manor also owed his allegiance to higher nobles and to the King. Ultimately, all wealth in the land belonged to the one guy who sat on the throne. He just shared it with everyone else. (Marylanders should understand this concept after weeks and weeks of Question 7 ads, which made it very clear that every dime possessed by a Marylander really belongs to our beloved Governor, and we don’t have the right to spend it in, say, West Virginia.)

But, if you lived in a tied cottage on the estate, you did not aspire to ever become the Lord of the Manor. That title would pass next to his idiot son. The only chance you stood was to marry his idiot daughter and father his idiot grandson, but the mechanisms in place to prevent that ever happening were efficient. Nor were you likely to accomplish the more modest goal of owning your tied cottage, it being, well, tied to the estate.

In very American fashion, Peter Bailey is trying to throw sand in the face of this system, helping others like him to own their own land, rather than “crawling to Potter,” the Lord of the Manor’s equivalent in this story, who seems to have forgotten to order the Christmas Hams. Bailey is enabling upward mobility, not by requesting government grants (he founded his Building and Loan long before these were made available), but by coordinating private resources and getting paid by his customers for his efforts.

When Peter started his Building & Loan, it was relatively outside of Federal interference. After all, in 1919 it’s already an established concern. By 1932, the Fed was subsidizing S & Ls and many cropped up. But Peter is not one of these opportunists. His concept was very American, very DIY. Distrust for the big guy is extremely American in character, because it’s a key component of independence. This is why rich villains work so well in American entertainment. The American psyche doesn’t like aristocrats, and shouldn’t. But this often gets used as leverage to make us distrust anyone who makes money. So a lot of people assume you must be evil if you’re rich, when, in fact, the American spirit should merely say, “I’m not going to be dependent upon you to get ahead.”

Sadly, though, Peter Bailey is not independent. He has borrowed from Potter and owes him $5,000. He doesn’t have it, and he’s asking for 30 days’ extension on his loan. He’ll come up with the money, he says, but he refuses to use any sort of pressure on his customers. Potter has no sympathy and tells Bailey to foreclose on them. Bailey won’t because these are families with children.

“They’re not my children,” is Potter’s only response, suggesting he has no responsibility to them. Very Scroogelike. But Bailey, unlike the judgmental ghosts from Dickens, does not tell Potter he should be the keeper of other people’s children, nor does he suggest that Potter owes him anything. He does remind Potter that he can’t begin to spend all his wealth, but, when Potter asks if he’s running a business or a charity ward, Bailey simply mutters, “Well, all right,” suggesting that he knows his business is not a charity. He simply believes that cutting people some slack will benefit his business in the long run. He may be right, he may be wrong. It’s his business.

But we see Potter as lacking sympathy for the working class and as being inflexible when it comes to business. Yes, he would turn a family out of their home. Or at least he thinks others should be willing to do so. That he does not give to charity is implied by Bailey’s suggestion that he can’t begin to spend all his money. Here, he’s a typical stereotype of a capitalist: He knows what’s his, and he feels no obligation to others.

But one other important aspect of Potter’s character shows up in this scene: he believes people are to be judged, not as individuals, but by their place in the social order. When young George, infuriated that Potter has called his father a “miserable failure,” rushes forward, shouting, and shoves Potter, Potter mutters, “Gives you an idea of the Baileys.” Here he’s suggesting that George is ill-bred, that his parents have failed to teach him manners. After all, in 1919, children were to be seen and not heard. They were never to speak in anger to adults, no matter how despicable the adult might be. So, never mind that George is showing loyalty, bravery and honesty, standing up to the most powerful man in town, he’s “ill-bred,” in Potter’s eyes. To a Crony Capitalist, social standing is of vital importance. Historically, successful capitalists have had no regard for class lines, often going from rags to riches and flouting conventional roles. But the Potters of the world know that their power depends on holding others back.

Bailey puts Potter on his Board of Directors for the Building and Loan, hoping that will give Potter more of an interest in seeing the business succeed. It doesn’t. Bailey describes Potter, later: “Oh, he’s a sick man. Frustrated and sick. Sick in his mind, sick in his soul, if he has one. Hates everybody that has anything that he can’t have. Hates us mostly, I guess.”

This is the first of several characterizations which suggest that Potter’s principle motivation is to own the property and thus control the lives of others. This is another important aspect of Crony Capitalism: you secure your wealth and power by making sure others don’t have more, instead of by being competent and producing wealth honestly.

In his next appearance, Potter bears out his opponent’s estimation of him. Peter Bailey has died, and Potter asks the Board of Directors to dissolve the business and turn its assets over to the receiver, presumably Potter himself. He’s not successful, because George demonstrates to the Board that he is a leader capable of carrying on his father’s work. In the course of the meeting, though, George describes Potter’s contempt for others: “People were human beings to [my father], but to you, a warped, frustrated old man, they’re cattle.” Throughout this exchange, Potter’s objection never seems to be that the business is losing money, but only that loans are being made to people that the bank wouldn’t loan money to. (Isn’t that the point of the business’s existence?)

There is a rather embarrassing paean to altruism in the speech George makes, honoring his father’s memory and attacking Potter: “Why, in the twenty-five years since he and Uncle Billy started this thing, he never once thought of himself. Isn’t that right, Uncle Billy? He didn’t save enough money to send Harry to school, let alone me. But he did help a few people get out of your slums, Mr. Potter.” This suggests that it’s virtuous that Bailey put the welfare of his family after the welfare of many, many others. That’s not virtuous, in my opinion, but “he never thought of himself” is a cliche accepted by many as a badge of merit.

But here again we see Potter’s nature: he wants the Building and Loan gone, so why doesn’t he buy it? Because that’s not how the Crony Capitalist plays his game. He uses his influence with others to get them to give him things he can’t or won’t pay for. He asks the Board to hand the assets of this business over to him, suggesting that he has no legal or legitimate alternative. The company doesn’t owe him enough money for him to simply say, “It’s time to pay up.” He’s trying to steal what isn’t his. A responsible capitalist knows that if he can get away with stealing, so can a lot of other people. His wealth will never be safe, so he doesn’t indulge in theft because it’s not in his best interests. But Potter believes he’s better than everyone else, and that he’ll get away with breaking the rules because they’re all too stupid to play that trick on him.

Here again, we’re reminded of the evil of serfdom, that it prevents you from getting ahead. Potter wants to prevent people from getting ahead — see his speech about a lazy rabble instead of a thrifty working class, countered by George’s challenge as to how long it takes a working man to save enough to buy a house. “What did you say just a minute ago? They had to wait and save their money before they even ought to think of a decent home. Wait! Wait for what? Until their children grow up and leave them? Until they’re so old and broken-down that they… Do you know how long it takes a working man to save five thousand dollars?”

The Baileys’ competence is demonstrated in the next Potter scene, which is in the middle of a run on the bank, presumably on the day of the Stock Market Crash of 1929. The Bank folds, and Potter buys it out by giving it money to continue operations. He tries a similar stunt with the Building and Loan, offering pennies on the dollar to shareholders. He’s not successful, and the Baileys, unlike many of their kind, survive the Depression, their business intact. It’s never said whether they do or don’t accept Federal subsidies, but they’re clearly shown surviving the crash itself by using the funds given to George as wedding gifts. Looters and moochers would not have been able to do that on their own devices. I suppose there are those who would say that George was being altruistic, trading his honeymoon for his business, but it would have been a pretty sad homecoming after the honeymoon if he hadn’t done it. The gesture served his own interests well.

And it’s a counterpoint to Potter’s earlier declaration: “Not with my money!” Potter is at that point telling Peter that he doesn’t have the right to spend on charitable or worthy causes money that doesn’t belong to him. It’s a valid and moral statement. And George supports his worthy cause with his money, playing by one of the few of Potter’s rules that is morally sound. Interestingly, “Not with my money” was a Barrymore catchphrase. His children said they used it around the house regularly, for their father had made it famous years earlier in You Can’t Take It With You. There, playing the lovable Grandpa Vanderhoff, he’d said it to an IRS agent, telling him he wasn’t willing to see Congress’s activities financed with his taxes. It’s a wonderful example of contempt for big government which way predates the Tea Party, though modern liberals believe distrust of government was invented by John McCain and the Koch Brothers. And, ironically, the sentiment is expressed in a play which also lampoons the red scare which eventually led to McCarthyism. If you haven’t seen this wonderful film, do so. It also features Samuel Hinds, Jimmy Stewart, H.B. Warner and Charles Lane from the cast of It’s A Wonderful Life, and is based on a play by legends George S. Kaufmann and Moss Hart.

So Potter is an opportunist who wants to profit off the misfortunes of others. That’s a common characterization of capitalists in Hollywood offerings. And those who believe that There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch will tell you that it’s not immoral to profit off of someone’s misfortune. Indeed, they’ll also tell you it is immoral to expect others to help you out of your misfortunes without profiting. Is Potter evil because he finds a way to make money while others are suffering? That’s the implication. I’d say his greater evil, however, is in trying once again to take what’s not his, the Bailey Building and Loan. His evil is his envy, his covetousness of what rightfully belongs to someone else. It’s not that Potter is rich that makes his behavior here evil. It’s that he thinks he somehow deserves what other people have earned. He would be just as villainous if he were the town drunk who felt that he should have George’s business because George got all the breaks in life and he didn’t. But the town drunk would be hard to turn into a credible villain. He wouldn’t have the resources to really harm George.

In this scene, Potter, like a good Crony Capitalist, mouths the words of altruism: “I may lose a fortune…” He’s implying that helping others is more important to him than money. As if! But this breed of dog always knows how to mouth the words of altruism to their advantage.

Potter’s next act is one of desperation. He tries to hire George, all other tactics having failed. George sees through this, though. The screenplay says it’s because George feels a physical revulsion when he touches Potter’s cold hand. I always assumed it was because he’d discovered sweaty palms and realized Potter was afraid his game would be discovered. Either way, George can’t be bought off.

The next encounter is the most telling about Potter’s character. George’s Uncle Billy goes to deposit $8,000 in cash at the bank. On the way he stops to gloat to Potter that George’s brother has won the Congressional Medal of Honor. When he does this, he sets down his newspaper containing the cash. Potter finds it and makes a hurried exit with it.

Henry F. Potter is a thief on a very large scale. But he doesn’t stop there. Oh no. George, knowing that the sudden disappearance of the money will result in his being charged with misappropriation, goes to Potter to ask for help. Potter calls the Sheriff, acting as a member of the Board of Director’s of George’s company, to swear out a warrant for George’s arrest. He does it in a particular way, too. When the Sheriff answers the phone, he says pleasantly, “Bill? This is Potter…”

Potter is never pleasant, and he has no friends. He’s pleasant because he’s about to use his connections and his influence to send an honest man to jail for a crime he committed. He knows, along the way, that this is the act that will finally win him the Building and Loan and complete control of the Town of Bedford Falls. This is not the act of a businessman. This is not the behavior of someone who knows how to honestly earn and keep money. This is the act of a warlord, a bully, a thug… a Crony Capitalist. It’s not what you know, it’s who you know. And Potter knows all the right people to help him win his battle and hang onto his ill-gotten gains.

By contrast, the good-guy Baileys never use force or extortion. Although Peter suggests that Potter should use his money to help others, he backs off when Potter says no and takes no action to force the issue. Peter Bailey had friends. So does his son. We see that at the end of the film when the whole town comes up with the money to save George and his business. These connections could be misused. If Peter or George had wanted to, they could easily have swayed the town to take Potter’s wealth. But instead they helped the townspeople mind their own business, tend to their own homes and advance their own standing. They never make a single more to take Potter’s wealth or try to control him.

George’s respect for the property of others is strongly demonstrated in the Bank Run scene. Tom, and old man, demands to be given every dollar in his account. George makes a heartfelt speech, telling all his customers that their money isn’t actually in the building, but is invested all over the town. Tom still demands his money. George gives it to him, even overlooking the 60-day delay he’s entitled to invoke. Because it’s Tom’s money, and he knows it. (Although he also labels the act as a “loan,” and tells Tom his account is still open. I suppose this could be construed to be George attempting to maintain control over Tom. I prefer to think it’s his way of saying, “You’ve been a good customer and I hope you’ll continue to be one.”)

In final analysis, Potter is not evil because he’s rich and the Baileys are not good because they’re middle class. Potter is evil because he’s a liar, a thief, a class bigot, and a person who wants to control others. In America, that’s a villain, anyone who wants to control the lives of others. Henry F. Potter couldn’t be a villain in a film today. Hollywood is too well aware that it is the rich Lord of the Manor, trying to protect its wealth by scotching the development of new technology, by writing travesties like SOPA, ACTA and ProtectIP, and hiring elected officials to attempt to make them law.

You won’t catch Henry F. Potter in a movie in 2012. But make no mistake. He’s alive and well. Wish we could trade him and all his ilk to get Barrymore back.

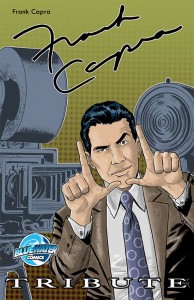

I somehow missed this when it came out in time for Christmas, 2012. In fact, I’m not 100% sure how I stumbled across it last week. Other than their Logan’s Run adaptations a while back, I don’t read too many Bluewater comics, so I doubt it was a house ad. Alas, that’s the nature of the Internet, especially when you’re as ADD as I am. Searching for one thing can lead to something you didn’t expect, which sets you on a mission. In this case, surfing around for something unrelated brought up a stray reference to a Capra tribute done in comic book form, and I had to find out what that was about. So whatever I’d been searching for was forgotten, and I had to jump on ComiXology and buy this.

I somehow missed this when it came out in time for Christmas, 2012. In fact, I’m not 100% sure how I stumbled across it last week. Other than their Logan’s Run adaptations a while back, I don’t read too many Bluewater comics, so I doubt it was a house ad. Alas, that’s the nature of the Internet, especially when you’re as ADD as I am. Searching for one thing can lead to something you didn’t expect, which sets you on a mission. In this case, surfing around for something unrelated brought up a stray reference to a Capra tribute done in comic book form, and I had to find out what that was about. So whatever I’d been searching for was forgotten, and I had to jump on ComiXology and buy this.