So, right up front, there’s some doubt about the name of this story. It is consistently called “The Hell-Bound Train” wherever mentioned in The Hugo Winners, Volume I. Wikipedia credits it as “That Hell-Bound Train,” matching the folksong from which it takes its name. Isfbd.org agrees with Wikipedia.

Robert Bloch is perhaps best known as the author of Psycho, the novel on which Alfred Hitchcock’s famous thriller of the same name was based, and of Psycho II, the novel on which Richard Franklin’s less-famous thriller of the same name was… not based.

Bloch’s work nearly always includes elements of horror, but he is known for science fiction stories as well, including the Star Trek episodes“Wolf in the Fold,” about Jack the Ripper, “Catspaw,” about the fabled civilization whose science is so advanced that it is indistinguishable from magic, and “What Are Little Girls Made of?”, about the killer androids created by a dread (and dead) civilization.

No surprise, then, that his first-and-only Hugo-winning short is not really a science fiction story, but a variation on Faust and many other tales of mortals trying to outwit the devil.

I was pretty much guaranteed to love this one. I love stories set on trains. I love ghost stories. (Listen here for a pretty creditable ghost story set on a train that I wrote and directed some years back.) And two of my favorite stories to tell are “Dead Aaron” and “Wicked John,” both about cantankerous characters who refuse to go to hell when it’s their time.

[Spoilers! It’s a short story, so I pretty much cover it all.]

Martin’s Daddy was a railroad man who used to sing a song about “That Hell-Bound Train” when he got drunk. When Daddy got drunk, that is. Martin doesn’t recall the words, but he knows that the devil himself drives the train to hell, and it’s the train that drunks and gamblers ride.

There is such a song—not the title track of Savoy Brown’s 1972 album, but a folk song. It was originally a poem, also called Tom Gray’s Dream, written by Retta M. Brown in 1893. (Also attributed to J. W. Pruitt.)

Martin’s Daddy gets pinned between two freight cars and killed, and Martin winds up in an orphanage. He runs away to become a railroad man and winds up as a hobo. One night, Martin sees it: That Hellbound Train, just as frightening as it’s described to be in the song. The drunks and gamblers on board are laughing and partying, having a literal hell of a time.

The train stops, and the “Conductor” hops off. He offers Martin a ride, which Martin, knowing the train’s ultimate destination, declines. “I suppose you’d prefer some sort of bargain, is that it?” The Conductor asks. Like us, he’s heard this story many times before.

After a little wrangling, the Conductor agrees that Martin can have whatever he wants, provided that, when the train comes for him, he boards it.

Martin asks to be able to stop Time, just once. (“Time” is capitalized in the story.) He’s going to live his life, wait until he’s perfectly happy, and then just stop Time. He could ask for wealth or power of Kim Novak, but he considers this deal foolproof.

“And you said I was worse than a used-car salesman,” says the Conductor.

So Martin lives his life. He decides that the path to happiness involves achieving financial success, so he gets a job. He gets an apartment. He gets a raise. He finds himself a nice girl, Lillian. Lillian encourages him to take further steps toward perfect happiness: a new house, decent furniture, a nice car… a son. Now he just needs to get rich and retire, and let Junior be happy, too.

Then he meets Sherry, who dosen’t see him as a middle-aged has-been. So he divorces Lillian, works harder, and makes a pile of money to replace the pile Lillian has taken. But Sherry doesn’t stick around while he’s rebuilding. So Martin takes a world cruise… and has a heart attack. The man with the power to stop Time is in a hospital, waiting to die.

Through all of this, Martin keeps waiting to use his power until things are “good enough,” until his happiness is perfect. It never is. So Martin boards That Hell-Bound Train without ever stopping Time. Martin joins the laughter and the partying… and then he stops Time. The Conductor moans, “We’ll just go on riding, all of us—forever!”

“The fun is in the trip, not the destination,” he tells the Conductor. “You taught me that.” Martin gets the job of Brakeman on the Hell-Bound Train.

This story is, indeed, a variation on “Wicked John.” If you’re not familiar with that one, it’s the origin of the Jack O’ Lantern. John was a mean blacksmith who once did St. Peter a favor. In return, the guardian of Heaven’s gates gave John three wishes. John’s misanthropic wishes all involved inconveniencing other people—people who borrowed his hammer, people who sat in his favorite rocking chair, people who broke switches off his thorn bush. John refused to go to hell when his time came. When subsequent demons, and then the Devil himself, arrived to collect him, he tricked them into using his hammer, sitting in his chair, and fiddling with his firethorn, trapping them in the process. And the condition for being let go was to leave John in peace. But everyone dies, so, when John just couldn’t stay on Earth any longer, he wandered up to the Pearly Gates. Peter had to say, “John, you did me a good turn, but you’re a bad man. We can’t take you. What would the neighborhood association say?” And when John traipsed down the long tunnel to The Pits, Satan said, “Aw HELL no!” So John took an ember of the diabolical fire and started his own little place out in the swamps, and that was the beginning of Jack O’ Lanterns.

Ironically, I used to tell this story to kids in church. They loved it. Later I was informed that this story was satanic in nature, and only a confirmed member of The Church of All Satans would tell it or enjoy it. The kids and I are still waiting on our membership cards. Been years.

Unlike John, it seems Martin is actually somewhat admired by The Conductor, or he’s just clever enough that he parleys his wish-granted supernatural powers into giving him a position in the Evil Empire, where John had to go and join the Libertarian Party or some such.

Also, unlike John, Martin is really the author of his own troubles. He was such a lazy good-for-nothing that The Conductor actually reached out to recruit him before his time came. Martin says to him, “You must want me, or else you wouldn’t have bothered to go out of your way to find me.”

And The Conductor admits, “I’d hate to lose you to the competition, after thinking of you as my own all these years.”

Indeed, Martin is, just before the train appears, considering going to the Salvation Army and allowing himself to be “converted.” The Conductor no doubt knows that Martin has it in him to be productive. Indeed, no sooner does Martin have incentive to improve his lot (getting to “perfect happiness”) than he undergoes a transformation to a Horatio Alger hero, snatches up his own bootstraps and gets rich. The Conductor saw this coming and took action to secure his soul for the Legions of the Damned.

But, his untapped, Ragged-Dick nature aside, Martin is still a douchebag at heart. He trades his wife in on a younger model to stoke the fires of his own vanity, allowing his son to be pulled out of his life. Then, abandoned by his young lover, but rich again, rather than use his second fortune to make amends, he squanders it all on luxury.

Wicked John? He just wanted to be left alone. Who among us doesn’t want people to stop borrowing our tools, stop loafing in our offices while we try to work, stop vandalizing our landscaping? And John was kind to weary travelers, viz. St Peter. If you think I have sympathy for Wicked John, you’re quite astute.

Bloch’s story is not at all science fiction, but it is witty and laced with American folklore.

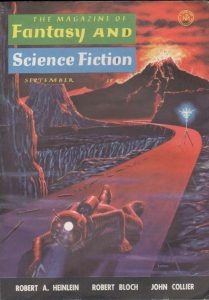

Readers of the September, 1958 issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction who wanted something harder and more “sciency” could take solace in the presence within the same pages of part two of the three-part serialization of Have Spacesuit, Will Travel. (Which lost out on the 1959 Hugo Award for best novel to James Blish’s A Case of Conscience. Having read both, I would have been in the minority on that vote.)