Review: The Darfsteller by Walter M. Miller, Jr.

It’s been a while since I blogged. When I started blogging weekly, a decade ago, I did reviews of books, comics and movies, with occasional essays on overall themes from science fiction and popular culture. I also occasionally talked about politics and social issues. In the years following my father’s death, I talked about the house that he had started building in 1967 and my work to move it toward completion.

Around 2019, life… happened. It took turns I did not expect, many of them. While I kept writing, I didn’t have the energy or the confidence to continue sharing my thoughts with the world.

Now, I’m trying to get back to blogging. I’ll start by doing what I used to—reviewing what I’m reading. Here goes.

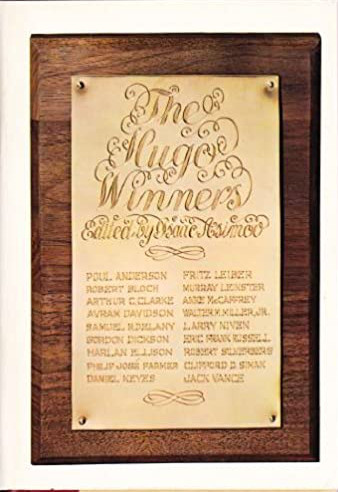

I picked up The Hugo Winners, Volumes 1 & 2 at a used bookstore in Liverpool, PA about two weeks ago. It was the only book I picked out that day. That is unusual for me, but I had a six-year-old—my grandson—dancing about my feet as I browsed, wailing that he was hungry, that he was bored, that I needed to help him explore the crawlspace in the bookstore’s basement. He had already picked out a book for himself—The Encyclopedia of Chess—and his work there was done. In the interests of keeping my shins and wrists intact, I picked out one book I did not yet own (I was pretty sure) and headed to the checkout.

I’ve started to make a habit of reading books I’ve just bought. Said grandson informed me yesterday that the rules clearly state you don’t read a book you’ve just bought. I sent him to the nearest law library to research jurisprudence on that one. Meantime, owning well over 3,000 books, I’ve decided it’s insensitive to a book to buy it, shelve it, and forget about it for decades. I have a lot of catching up to do on the older stock, but I’m trying to stop the bleed by quickly reading the new acquisitions. It’s okay, the older ones still have a chance. I read about six books at once, to the dismay of my wife, and the detriment of end tables, book bins and sofas.

Isaac Asimov edited all five volumes of The Hugo Winners. He says he was uniquely qualified, having never won an award himself. He wrote those words in 1962. He has since won ten Hugos. It’s an interesting word, “Editor.” The editor of an anthology generally either selects the works within or edits the text of the entries, or both. Since the works were pre-selected by virtue of winning the award, and, presumably, the stories were not changed or re-written from the forms which won them the award, it’s a bit daunting to divine what editing Asimov did, apart from stories about his experiences with the authors. Interesting stories, yes, but they don’t constitute “editing.”

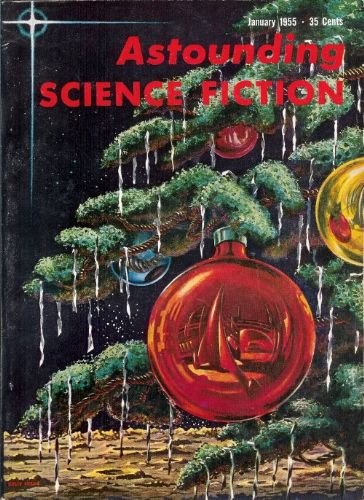

The first of these stories is “The Darfsteller,” by Walter M. Miller, Jr., who would later win the Hugo for best novel with “A Canticle for Liebowitz” (1961). This piece about a frustrated actor won for best novelette at the 13th World Science Fiction Convention (WorldCon) in 1955. That was the first year the Hugos were given out. “The Darfsteller’s” relevance to the world we live in in 2022 demonstrates that good science fiction looks forward with a strong sense of what’s happening in the present and is not rendered irrelevant by time. That’s the reason I like older science fiction. It makes its point about society without drowning me in an author’s emotions and opinions about all-too-fresh events. I find modern science fiction myopic and tiresome. It lacks perspective and its voice is angry. Older generations of authors have detachment from the issues of today, even if, in their times, they were myopic and angry. I can usually decide to find out-of-date anger charming.

On to the story…

Ryan “Thorny” Thornier works as a custodian in a theater run by a sadly stereotyped Italian American named Imperio D’Uccia. Thorny hates his boss, and the feeling is mutual. But Thorny can’t get a job that fulfills him emotionally. The job he was trained for no longer exists. Thorny, you see, was an actor in the live theater. In the time in which the story is set, there is no more live theater. Plays, movies and television shows are performed by robots—animated mannequins which move as directed by “The Maestro.” “The Maestro” is an artificial intelligence that, using recordings of performances laid down by human actors, “directs” the robots as they move and speak in the style of those human actors.

All the very famous thespians have sold the rights to their voices, their likenesses, and their style of movement. Thorny considers this the moral equivalent of prostitution. Thorny, we are told, is a Darfsteller. Don’t bother looking up the word in a dictionary, not even a German one. Miller apparently created it. He defines it twice, first in dialog as, “A director’s ulcer. You can’t play a role without living it, and you won’t live it unless you believe it.” Later, in narrative, he calls it, “The self-directed actor,” and “the undirected portrayer whose acting welled from unconscious sources with no external strings.” He contrasts this, disparagingly, with the “schauspieler, the actor that a director could play like an instrument.”

Wikipedia speculates that “darfsteller” is a portmanteau of the German “darsteller” (actor) and “darf” (to be at liberty to do something). “Schauspieler” also simply means “actor” in German. Miller’s, or at least Thorny’s, distinction between the two is clear: there are actors who do as they’re told, and might as well be robots, and there are individualists who must answer to a higher authority than a director—human or machine.

Thorny is not one of the “famous thespians” whose likeness et al commanded a high royalty. His former lover, Mela Stone, is one of that fortunate few, and is growing fat (only figuratively) on the proceeds. Thorny, on the other hand, almost had his big break—acting opposite Mela—in “The Anarch,” many years ago; but the production folded before opening night. Thorny went unpaid and unremembered—except by many former colleagues, who wonder how in hell he can stand working for a despot like “Dooch” D’Uccia. (One wonders if D’Uccia really misses that his colleagues are calling him “Douche” to his face. One also notes with interest that “The Anarch” is pretty clearly about the fall of the Soviet Union, and Miller was writing over 35 years before that fall happened.)

Truth is Thorny can’t stand working for Dooch much longer. In fact, he arranges a quite-mean practical joke on his boss by way of a resignation, leaving Dooch to proclaim that he’ll hire an auto-sweeper to take Thorny’s place as a custodian, just as a robot took his place as an actor.

It’s not just Dooch’s less-than-magnetic personality that has driven Thorny to the brink, it’s the fact that acting, the one thing he’s good at, is just no longer a career. Because of automation, audiences will forevermore see “the best” actors—read, always the same actors—in every role. There will be no chance for a Jacobi or Branagh to replace Olivier in the minds of audiences as the greatest Hamlet, because whichever actor laid down the “tape” of the performance will be Hamlet until the end of time. (Yes, it is funny that science fiction authors through most of the 20th Century believed that tape would always be the best medium for data storage. If only we could send John Cleese’s “Institute for Backup Trauma” PSA back to Hugo Gernsback via Tachyon transmission.)

Whena performance of “The Anarch” is brought to D’Uccia’s theater, and it stars a robot programmed to ape Mela Stone, Thorny develops a clever—potentially suicidal—plan to sabotage the production and be a star one last time.

Miller was, to gauge by this story and his “Canticle,” a keen observer of the social effects of new technologies. We have not reached the point at which live actors are replaced by robots (although we have reached the point where dead actors live again via CGI), but we have seen many jobs and skills fall by the wayside during my lifetime. You took a class to learn to type? Shorthand? What’s that? Wait, someone drew the defendants in court cases? By hand? Let’s not even talk about the profession of draftsman.

Miller understood that life was not going to stay exactly as it was in the sunny days following the Second World War in America. (Something beyond the grasp of our national politicians even today.) Technology would bring change, and people who had trained all their lives to hand-paint company logos on widgets would suddenly be looking for a job.

The theme of “The Darfsteller,” still relevant today, is summed up on its last page, presented here, relatively spoiler-free:

Thorny says to his friend, “It’s too late to find a permanent niche.”

His friend replies, “It was too late when you were born old man! There isn’t any such thing—hasn’t been for the last century. Whatever you specialize in, another specialty will either gobble you up or find a way to replace you. If you get what looks like a secure niche somebody will come along and wall you up in it and write your epitaph on it. And the more specialized a society gets, the more dangerous it is for the pure specialist … You’ve got one specialty that’s safe… The specialty of creating new specialties. Continuously. On your own… More or less a definition of Man, isn’t it?”

Relevant words to this day—especially to people in the I.T. field. My wife, an I.T. Project Manager, has the word “Adapt” tattooed on her wrist, to remind her that it’s the one thing we have to do every day, on the job, and in life. As Miller observed, more or less the definition of humankind.