I happened upon this volume almost by accident. I’ve always been a huge fan of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s 1975 – 1977 science fiction series, Space: 1999. I’ve got a bit of a chip on my shoulder about it, in fact, because the show seems to provoke resentment from most corners of Fandom. If you’re a fan over the age of about 35, you remember how it felt to like Star Trek or comic books, back before Fandom became just another cash cow for Hollywood? Before the Marvel Movies conquered the box office? Before The Big Bang Theory? (The show, not the actual theory. Note the italics. Punctuation is key.) Before geek was chic?

I happened upon this volume almost by accident. I’ve always been a huge fan of Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s 1975 – 1977 science fiction series, Space: 1999. I’ve got a bit of a chip on my shoulder about it, in fact, because the show seems to provoke resentment from most corners of Fandom. If you’re a fan over the age of about 35, you remember how it felt to like Star Trek or comic books, back before Fandom became just another cash cow for Hollywood? Before the Marvel Movies conquered the box office? Before The Big Bang Theory? (The show, not the actual theory. Note the italics. Punctuation is key.) Before geek was chic?

Yeah, it was a bad feeling to be a fan in those days. Everyone looked down on you, to include your peers, siblings, teachers, sometimes even your parents! Well, as bad as that felt for, say a Star Trek fan, it was worse for a Space: 1999 fan. Everyone looked down on us, including all other fans! To this day, I’m careful at cons and on panel discussions about mentioning my love of this series, because people actually groan in revulsion.

Why? I’m not sure. Everyone old enough to have watched TV in the 1970s remembers the Eagle spaceships and thinks they were cool. Most of the same people who revile 1999 love Star Wars, not realizing that the maligned TV show set the standard of special effects that George Lucas wanted to equal or surpass when he made a space movie. But detractors cite 1999’s “wooden acting” and “scientific implausibility.”

“Wooden acting?” I disallow this argument. It’s a copout used by people who don’t like something and don’t know why. “Oh, the acting was terrible!” What does that even mean? How do you measure goodness and badness in acting? I’m trained in stage-acting, and I don’t know. I know the techniques for researching and developing a part to make myself act well, but I don’t know of any objective standard for measuring acting in others. I can say, “I don’t believe you’re feeling what the character would feel in that situation,” but I don’t actually know what that character would feel in that situation. Oh, I can tell if someone is too nervous to perform, has poor diction, is doing a bad accent, or doesn’t actually know any technique for simulating the emotional responses of a character. But actors that bad don’t get on television at all. So, criticizing the acting in a professional production is almost always a cheap shot, and should be inadmissible in any court.

“Wooden acting?” I disallow this argument. It’s a copout used by people who don’t like something and don’t know why. “Oh, the acting was terrible!” What does that even mean? How do you measure goodness and badness in acting? I’m trained in stage-acting, and I don’t know. I know the techniques for researching and developing a part to make myself act well, but I don’t know of any objective standard for measuring acting in others. I can say, “I don’t believe you’re feeling what the character would feel in that situation,” but I don’t actually know what that character would feel in that situation. Oh, I can tell if someone is too nervous to perform, has poor diction, is doing a bad accent, or doesn’t actually know any technique for simulating the emotional responses of a character. But actors that bad don’t get on television at all. So, criticizing the acting in a professional production is almost always a cheap shot, and should be inadmissible in any court.

“Scientific Implausibility?” Some of the greatest stories ever told are scientifically or otherwise implausible. Animals can’t talk. Little girls could not possibly mistake a wolves in frocks for their grandmothers. Scarlett O’Hara wouldn’t have made 19 before someone got fed up and clubbed her to death. Star Trek is scientifically implausible, as is any story that posits FTL travel, or suggests that creatures evolved separately on different planets could interbreed. Both the Enterprise and Mr. Spock are implausible. That doesn’t make them any less wonderful.

These flaws are overlooked in many, many properties which succeed. Many more properties slip quietly into obscurity, not because of these flaws, but because they just didn’t catch a mass audience the right way at the right time. Tastes are fleeting and fickle. But those failed shows don’t usually provoke animosity. They just cause people to say, “I really never cared for that show.”

But Space: 1999 draws animosity. And I can’t tell you why.

Back to the accident that caused me to acquire, read and review this volume, To Everything That Was. I buy a lot of books and comics, far more than I have time to read, especially lately. I visit my local comic store, Cosmic Comix, weekly. But I don’t tend to keep up very well with what’s coming out soon. I don’t read a lot of comics news sites, I don’t subscribe to Previews from Diamond… I’m often out of the loop. That means I miss some good things that come out, unless Rusty at CCX has stocked ample quantities of them. Well, he can’t stock ample quantities of some of the more obscure titles, because he’d lose money. I never see some comics on the shelves, and thus don’t know they even exist.

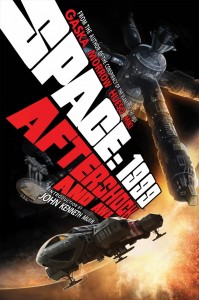

So, once every couple of months, I try to check out the comic sites and review lists of everything that’s been released. (Comixology is making this a lot easier to do.) While I was at MystiCon over a year ago, chilling in my hotel room, I scanned one of those lists and saw that the latest issue of something called Space: 1999 – Aftershock and Awe had been released by someone called Blam! Ventures. What? A new Space: 1999 comic? There hadn’t been one in about 35 years! So I checked their site, found preview art, and right away ordered a hardcover of this new graphic novel. I was very pleased with it. The creative team had taken an old adaptation of the Space: 1999 pilot episode, “Breakaway,” colored it (the Gray Morrow artwork was original published in black and white) and re-written the text and some of the dialogue. Then they’d interlaced original artwork and story, and built a re-imagined-but-still-faithful version of the first hour of Space: 1999. Great fun.

So, once every couple of months, I try to check out the comic sites and review lists of everything that’s been released. (Comixology is making this a lot easier to do.) While I was at MystiCon over a year ago, chilling in my hotel room, I scanned one of those lists and saw that the latest issue of something called Space: 1999 – Aftershock and Awe had been released by someone called Blam! Ventures. What? A new Space: 1999 comic? There hadn’t been one in about 35 years! So I checked their site, found preview art, and right away ordered a hardcover of this new graphic novel. I was very pleased with it. The creative team had taken an old adaptation of the Space: 1999 pilot episode, “Breakaway,” colored it (the Gray Morrow artwork was original published in black and white) and re-written the text and some of the dialogue. Then they’d interlaced original artwork and story, and built a re-imagined-but-still-faithful version of the first hour of Space: 1999. Great fun.

Fast-forward over a year, and I’m reviewing emails from the wonderful Inge Heyer, chairperson of Shore Leave, the oldest remaining Star Trek convention, to all the author guests of this year’s con. Among the names I see a first-time guest named Andrew Gaska. I remembered Andrew as the author of Aftershock and Awe, and so I shamelessly snatched his email address and sent a private message congratulating him on his achievement, and telling him I was looking forward to meeting him. I also volunteered to join him on a panel about playing in other creators’ universes, along with three other authors. (I suppose some authors would be annoyed to receive a fan email from a fellow guest via a group list from a con, but Andrew did not seem annoyed.)

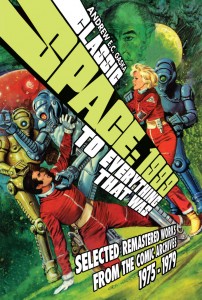

Sadly, only Andrew, his cohort Katie, and I showed up for our panel. So we spent the hour trading war stories about dealing with licensing (he has a lot more experience with it than I do, but I have a little), and spouting Space: 1999 trivia. In the course of the conversation, he told me he’d sadly lost the license to 1999 after publishing only two graphic novels. Well, that was one more than I knew he’d produced, so I promised I’d come by his table with money. In fact, he graciously requested a copy of Firebringer’s new anthology, Somewhere in the Middle of Eternity, in lieu of money. So I came home with an autographed copy of To Everything That Was, in which Andrew and his team had once again assembled material from 1999 comics of the past, done a little re-writing and re-drawing, and created an epic story which spans about five years.

One of the most jarring aspects of Space: 1999 for loyal viewers who care about continuity was the major overhaul the show received for its second series. No less than four regular characters disappeared without mention, including Victor Bergman, played by headliner Barry Morse. Costumes were changed, sets drastically changed, and the tone of show went from sombre and philosophical to comedic action-adventure. Two factors brought about these changes. One, the show’s budget was drastically curtailed. The cast had to be smaller, and often two episodes were filmed simultaneously, so that the cast was split between them. Two, ITV America took a much greater hand in development, replacing British show-runners Gerry and Sylvia Anderson (who also divorced between series) with very American producer Freddie Frieburger, known already for killing Star Trek, and later to be known for killing Superboy. Frieburger’s job was to make the esoteric show “accessible” to Americans, whom we all know are a dull, tiresome, unimaginative lot.

Change is one thing, but drastic and unexplained change leaves viewers who pay attention unsatisfied. As a kid, I loved the second series. Still do. It’s fun. Silly, monster-of-the-week, often absurd, fun. Catherine Schell is adorable as Maya the shape-changing alien, and the atmosphere is comfortable for anyone who was a fan of DC Comics in the 1970s. Still, it’s a pretty far leap to take from one series to another. Anyone who, like Gaska, wants to make sense of both series and tie them together, has a big job on his hands. So he uses stories intended to be non-continuity changing pieces that fit neatly into Year One of the show, and, with a little tweaking, has them explain why four characters disappeared, why Moonbase Alpha, the characters’ home, looked so different, why a group of people presumably short on raw materials decided to design new uniforms, and even why their adventures had a different tone in the second year (which Gaska declares to actually be the fourth year) or their journey through space.

One of the first re-written stories included in the volume is told from the point of view of Tony Verdeschi, a character who appeared only in Year Two, and yet was presented as having always been there. Suddenly this guy who was not important enough to be seen was second in command. Gaska takes the clever step of telling the story in a way that it makes sense that Tony doesn’t appear (because he’s narrating), and yet he’s critical to the plot. Throughout the ensuing, Year One-based stories, he makes Tony’s role ever more important, re-drawing faces where necessary, so that it makes sense when he’s entrusted with being Commander John Koenig’s Number One.

I particularly like Gaska’s use of minor characters from both the TV series and the comics. For one, there’s the continuation of a twist he added in his first novel, Aftershock and Awe. In Year Two, a lovely young actress name Lynne Frederick (at the time the wife of Peter Sellers) appeared one time as a teenaged botanist. At almost 13, I fell immediately in love with the character of Shermeen Williams. Apparently I wasn’t the only one. Gaska includes her right from the beginning in his retelling of the series opener, chronicling how a nine-year-old visitor to the Moonbase lost her parents when a nuclear disaster propelled the Moon out of Earth orbit, and how she came to be adopted by Professor Victor Bergman, the genial old father / advisor to the residents of the Moon city. None of this was canon in the show, but it makes perfect sense. Someone had to be raising the girl from childhood before she appeared as a teen late in their journey.

I particularly like Gaska’s use of minor characters from both the TV series and the comics. For one, there’s the continuation of a twist he added in his first novel, Aftershock and Awe. In Year Two, a lovely young actress name Lynne Frederick (at the time the wife of Peter Sellers) appeared one time as a teenaged botanist. At almost 13, I fell immediately in love with the character of Shermeen Williams. Apparently I wasn’t the only one. Gaska includes her right from the beginning in his retelling of the series opener, chronicling how a nine-year-old visitor to the Moonbase lost her parents when a nuclear disaster propelled the Moon out of Earth orbit, and how she came to be adopted by Professor Victor Bergman, the genial old father / advisor to the residents of the Moon city. None of this was canon in the show, but it makes perfect sense. Someone had to be raising the girl from childhood before she appeared as a teen late in their journey.

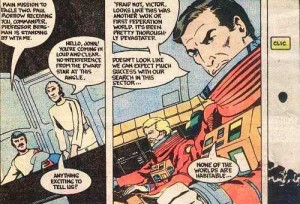

Mal Burns is a character who never appeared in the show. He was created by comic book legend John Byrne, who had a propensity for adding young, blond, bearded blokes to his stories. Byrne was, in the 1970s, blond and bearded, and Space: 1999 from Charlton Comics was one of his first jobs. As Professor Bergman’s assistant, Mal didn’t do a whole lot, although it’s notable that he co-piloted an Eagle with Commander Koenig in one story… and lived. (In Space: 1999, the co-pilots almost always died. They were Moonbase Alpha’s red-shirts.) Gaska puts young Burns to good use here, adding him into stories where he didn’t originally appear, and revealing that, despite the Professor’s plans for him to marry young Shermeen, he’s “more interested in the Professor.” I laughed out loud at that one.

Mal Burns is a character who never appeared in the show. He was created by comic book legend John Byrne, who had a propensity for adding young, blond, bearded blokes to his stories. Byrne was, in the 1970s, blond and bearded, and Space: 1999 from Charlton Comics was one of his first jobs. As Professor Bergman’s assistant, Mal didn’t do a whole lot, although it’s notable that he co-piloted an Eagle with Commander Koenig in one story… and lived. (In Space: 1999, the co-pilots almost always died. They were Moonbase Alpha’s red-shirts.) Gaska puts young Burns to good use here, adding him into stories where he didn’t originally appear, and revealing that, despite the Professor’s plans for him to marry young Shermeen, he’s “more interested in the Professor.” I laughed out loud at that one.

There’s even a cameo by Alpha’s youngest resident, Jackie Crawford. Jackie was introduced in the series as the first baby born on the Moon, an unfortunate who was promptly taken over by aliens. But little Jackie was saved and allowed to live on… without ever appearing again. And, in the novels published recently by Powys Books, the poor kid isn’t even allowed that. He’s killed off by yet another alien interaction. I was not amused by that story, and I’m glad that, again, Gaska’s views seem to align with mine. Jackie makes it to the end of this book alive and well, if only in one panel.

There’s even a cameo by Alpha’s youngest resident, Jackie Crawford. Jackie was introduced in the series as the first baby born on the Moon, an unfortunate who was promptly taken over by aliens. But little Jackie was saved and allowed to live on… without ever appearing again. And, in the novels published recently by Powys Books, the poor kid isn’t even allowed that. He’s killed off by yet another alien interaction. I was not amused by that story, and I’m glad that, again, Gaska’s views seem to align with mine. Jackie makes it to the end of this book alive and well, if only in one panel.

A dead TV series and a bunch of 40-year-old comic book adaptations… who cares? Well, I do, and I think the fine folks at Blam! Ventures must. At least enough to create two beautiful volumes of story out of quite a few old magazines and comic books. The bad news is that someone else who cares, the team that’s planning to make a show called Space: 2099, has caused their to be no more of these volumes. Probably through no fault of that production team, ITV, the copyright owner, perhaps not wanting to dilute their franchise, has not been responsive about any possible future releases under Blam!’s license. It’s too bad. I would have liked to have seen a lot more.

Oh, one more thing… the title. In an early episode of Space: 1999, Moonbase Alpha passes through a black hole. They call it a black sun. I guess it sounded more poetic, or perhaps that was an English colloquialism at the time. Anyway, as they think they’re about to die, Command John Koenig and Professor Victor Bergman get drunk together on brandy. Koenig proposes a toast, “To everything that might have been.” Bergman counters him, “To everything that was.” It’s a touching moment, and the message is life-affirming. Don’t second-guess yourself. Play the hand you’re dealt. You may find that “it is what it is,” winds up in hindsight meaning, “it wasn’t really so bad.” The week before I discovered Andrew’s work, I quoted Professor Bergman as I raised a toast to the opening night of my con, Farpoint’s, 20th anniversary. I’m partial to it, and I’m very pleased that it was chosen as the title of this fine collection.

Shermeen rocks. You know it.

Thank you for this article. I just placed an order for “Aftershock and Awe.”