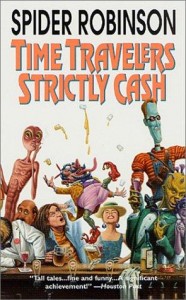

I’ve been listening (a few stories at a time) to The Callahan Chronicals, read by Barrett Whitener. I listened through all of the stories from Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon a while back, and just listened through the stories from Time Travelers Strictly Cash. A couple of things worth noting for the collector or bibliographer:

I’ve been listening (a few stories at a time) to The Callahan Chronicals, read by Barrett Whitener. I listened through all of the stories from Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon a while back, and just listened through the stories from Time Travelers Strictly Cash. A couple of things worth noting for the collector or bibliographer:

1) This is a 1997 re-issue of Callahan and Company, published 1988. It contains stories from Callahan’s Crosstime Saloon, Time Travelers Strictly Cash and Callahan’s Secret.

2) It does not contain all the stories from Time Travelers Strictly Cash. It contains only the stories which take place at Callahan’s Place, a fictional (some readers would disagree) bar somewhere in the wilds of Long Island.

So, because I’m a bit OCD and because I like to document my reading, I decided to list on my activity page, not that I was reading / listening to Chronicals for more than a year, but that I was reading each component book fairly quickly. (I use Goodreads for the purpose. It’s so nice to know I’m not the only one who thinks his reading habits matter a tinker’s dam* to anyone else!) So I listed Time Travelers Strictly Cash as my current book for a bit, only to discover that I wasn’t listening to all of it. Well, I couldn’t very well lie to Goodreads, now could I? For those damned souls who dare is reserved the special hell, where go virtual sex criminals and people who blog loudly in the theatre.

I therefore had to secure the book and read the rest of the stories. I’m glad I did. The rest included Spider’s treatise (in story form) on reincarnation, the first of his regular book review columns from back in the day, his tribute to the great Robert A. Heinlein (“Rah Rah R.A.H”), a truly silly fan guest of honor speech from MiniCon, (I may steal it to be the keynote at the next Farpoint, it’s that good!), and “Serpents’ Teeth.” It also includes Spider’s personal reflections on each of the entries, which Chronicals does not. So, if you’re a Spider fan, seek out the individual books at your nearest used book store. Or a used book store in whatever town you happen to be visiting today. (You do visit a used book store in every town you visit, don’t you? I do. Thomas Jefferson did. Captain Jan Atal does. Do I need to say any more?)

If you’re not a Spider Robinson fan, read any of the books, stories or articles named herein. You will be. That, or you probably aren’t enjoying my blog, either, and why are you reading it anyway?

Now, I’m about to do a spoiler alert. That means you should stop reading if you don’t want to know the ending or any details of the story which are unclear until late in the story. “But Steve, what’s the point of a review if you spoiler-alert it before you start actually talking about the story?” Okay, you want something before I start spoiling? Here ya go:

Teddy and Freddy walk into a bar. They’re looking for a date. A 9-year-old named Davy looks like their boy.

(Don’t worry. It’s gonna be okay. I wouldn’t tell you to read a story where Teddy and Freddy actually picked up a 9-year-old boy in the way you’re thinking, you dirty-minded sod. This goes somewhere else entirely, but my capsule summary is accurate. )

There. You’ve got the idea. It’s less creepy with spoilers.

SPOILER ALERT – STOP NOW IF YOU WANT TO BE SURPRISED!

“Serpents’ Teeth” was ruined for me. Well, not ruined, but spoiled. When I went to check out which stories were in The Callahan Chronicles (I forget why, but it was then that I discovered some were missing) I read a wiki article on the volume, and it was there that the story was summarized in one sentence which gave away the works.

Here’s the deal: Teddy and Freddy walk into a bar. (It’s called “The Lookover Lounge.”) At first, you don’t know their genders or their relationship. First spoiler: Teddy’s a girl, Teddy’s a boy, they’re married, their also partners on the police force.

At the entrance to the bar are the house rules. Most prominent of these is that no bar patron is to be removed from the premises against his or her will, and management will hurt anyone who tries (or words to that effect.)

Teddy and Freddy go in, are very concerned that they’ll look like hicks, that they’ll say the wrong thing, that the person they’re seeking will know what they’re after, and they’ll blow their shot. They see a blonde boy dancing. He’s breathtaking to look at, and they’re intrigued. He comes over and claims they stole his seat. They invite him to join them. They offer him a drink. He orders beer.

His name is Davy, and he tells them he’s nine years old. Of course, he only reveals this intensely private detail of his life after they reveal how often they have sex.

Davy proceeds to interview the couple and be interviewed. We learn that Teddy and Freddy’s own child, Eddie (Davy gives them no end of grief for that name) divorced them for daring to have plans for him. The most damning charge at the hearing was “delusions of ownership,” something no parent, apparently, should have. (And of course that’s true, but I think damn near all of use would lose our children if we had to defend against the accusation.)

During the interview we realize that, even though they’re attempting to pick him up in a club, they’re not trying to seduce this child. The club is where prospective adoptive parents go to look over children, and be looked over in return. The rule about removing anyone from the premises unwillingly suddenly makes sense. It’s up to the kid to decide if he or she wants to be adopted. It’s up to the parents to induce the kid to accept. It’s never explained why all these kids in the bar are parentless, but we do learn that any child six and older can pretty easily divorce his parents. We infer that these are kids who made the break, but are still, for whatever reason, willing to try again.

Davy mentally and emotionally rakes Teddy and Freddy over the coals, then tells them he’ll give it a try. He’ll go with them for two weeks. He quickly realizes that they wanted a permanent situation, and he laughs uproariously. “On a first date?” He demands.

Teddy, Freddy and Davy do not get together. Perhaps it’s because their names don’t rhyme. Pop, the bartender, speculates that’s because Davy is “a little vampire.” Apparently he’s done this to a lot of people. The parallels to the 20th Century dating scene are fire. Adults having a drink with a kid is a “date,” a kid deciding to partner up with parents is “getting married.” When you think about it, it’s fairly apt. If we could pick our parents, we would certainly solemnize it as much as we (claim to) solemnize marriage.

It’s a thought-provoking story, which is what good SF is. It makes you ask, “Just what the hell is going on here?” and then it makes you ask, “Wow, what if things were really like that? Should they be? Why or why not?” Spider, in his afterward, says it grew out of his observation that, in the latter half of the 20th Century, a lot of groups of people were getting liberated. Why not kids? And what are the limits of parental authority? He had just become a parent in the preceding few years when he wrote this. Wonder what he thinks now.

It’s a funny little story, yet touching. It describes people who are like you, like people you know, people you sympathize with almost immediately. (That is, immediately after you realize they’re not child-molesters.) It’s the kind of story Spider tells well.

Oh, the spoiler I read? It told me that the story was about a couple who wanted to adopt a child. It drives right to the point, but somehow misses it, that description. As with any good story, it’s the characters that make it so much more than its summary.

* Do you know what a tinker’s dam is? I didn’t. It’s a small container formed of dough, meant to keep solder from escaping the immediate work area of the tinker while a tinker repaired a pot or pan. Once the dough is used for this purpose, it’s worthless. Hence the expression “I don’t give a tinker’s dam,” may be equivalent to saying, “What you’re talking about is worth no more to me than the material the pot-welder throws in the trash.” And the phrase, over time, may have been shortened to “I don’t give a dam.” If that’s the true source of the expression, then “I don’t give a damn” is grammatically incorrect. Of course, then there’s the expression, “I don’t give a tinker’s cuss.” Which I guess means that tinkers swore a lot, and there oaths were worth less than the oaths of other members of society. Does anyone give either a damn or a dam which it is?