August 9, 2022

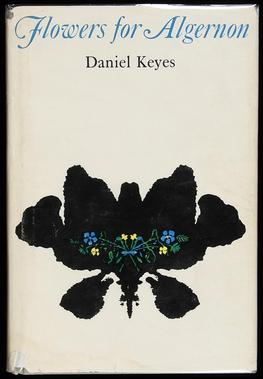

This story has always haunted me. They made us read it in 8th grade, and my almost-next-door neighbor Brian had told me the story of the film. He told me the stories of lots of films. He was two years older than I, and far more worldly. The novel was on the shelf at our school library, where I spent most of my recess periods. The cover is one of the things that haunted me. It depicts a Rorschach inkblot, with some flowers laying on top of it. When I was 10 or 11, I didn’t know what a Rorschach test was. I thought the cover was some Avant Garde representation of a brain, suggesting the torturous horrors of opening up a skull and performing surgery on the brain within. (I didn’t know what Avant Garde was either, but it describes the gist of my impression then.)

How’s that for a glimpse of my psyche? Ironic that, like the hero of the story, I had no idea what a Rorschach test was; but, unlike Charlie Gordon, I was quite capable to taking one.

It was actually the short version, which predates the novel, that was the award-winner. I didn’t actually realize “Algernon” was a Hugo winner until I picked up this volume. I suppose I was vaguely aware it was science fiction, but I probably shunted that thought to the back of my mind. As a kid, I thought of science fiction as something pleasurable to read, and I didn’t really see any overlap of the Venn Diagram bubbles for “Stuff I enjoy” and “Stuff I was assigned at school.”

English teachers have—or had in the dim days of the 1970s—a propensity for assigning depressing stories to their students. Maybe it’s an attempt to calm us down? (You notice that, though I’ve been a teacher myself over the years, I automatically align myself with students by saying, “Us.” We never grow up in our own heads.) I mean, seriously, The Human Comedy? A Separate Peace? The Great Gatsby? Native Son? Crime and Punishment? (I mean, I guess… I never finished it, despite the assurances of Cassie, who sat next to me in 12th Grade English, that it “really picked up after the first 400 pages.” Get to the point, Fyodor!)

“Flowers for Algernon” the short story is of that genre. I assume the novel is as well. I own it, but have not read it. It’s also a touching and haunting story—haunting for more than just the sinister Rorschach images on the book cover.

It tells the story of Charlie Gordon, a janitor at a plastic box factory. Charlie has an IQ of 68. He loves his job, loves living in the boarding house kept by Mrs. Flynn, and loves his friends at work. He doesn’t mind that they laugh at him or refer to making a mistake as “pulling a Charlie Gordon.” He thinks that just means he’s important.

But Charlie wants to better himself, and so he attends night school classes taught by Miss Kinnian. He has learned to read a little and write a little, and Miss Kinnian has recommended him as a candidate for an experimental surgery which may triple his IQ. To establish a baseline, Charlie “races” a lab mouse named Algernon. Algernon runs in a maze and Charlie works the same maze on paper. Algernon always wins because Algernon has already had the surgery to triple his intelligence.

The story is told by Charlie himself in a series of progress reports (“Progris Riports” in early days). Through these narratives, we can see Charlie progress from low literacy to speaking dozens of languages and considering the calculus of variations to be “basic arithmetic.” The operation, it seems, is a success. At the top of his game, Charlie is in love with his teacher and installed at the lab where he had his surgery, performing his own research into the maximization of human intelligence. In fact, it is Charlie who finds the flaw in the procedures used to boost both his and Algernon’s mental faculties. It is Charlie who recognizes the growing evidence that his gifts have an expiration date.

As a teenager, the idea of gaining and losing intelligence is an abstract. You’re still on the upward climb towards your own peak of intellectual power. You may know someone who, like Charlie, is well below the pinnacle of the bell curve of IQ distribution, but you’ve likely not seen anyone sink backwards from the pinnacle to the trough. Having a 13-year-old read this story may be a pointless exercise.

To a man approaching sixty, having seen a father to his death with Alzheimer’s, and now watching my mother, with another form of dementia, asking me why she can no longer balance her checkbook, or read a novel, or watch TV… Charlie’s tragedy is not abstract. It’s very, very real. Perhaps the worst part of losing your intellect is know that it’s happening to you and knowing that it can only get worse.

It leaves one asking, “Why am I still here?”

Not a hopeful thought, but, indeed, a very haunting one.