Flashback to high school – Nineteen-eighty… something. War games were catching on. There were role-playing games in the wake of Dungeons & Dragons, then only about five years old; there were those bookcase-packaged strategy games from Avalon Hill, and those trays of maps and cardboard chits from… was it TSR? I bought a lot of them. Rarely played them. Then came to my high school the first L.A.R.P. (Live Action Role-Play) I ever encountered. I think, though I can’t swear, that it was called Chaos. Or Kaos? It involved stalking opponents through the hallways of the school and attacking them (theoretically, of course for these were math and science geeks doing the attacking.)

Flashback to high school – Nineteen-eighty… something. War games were catching on. There were role-playing games in the wake of Dungeons & Dragons, then only about five years old; there were those bookcase-packaged strategy games from Avalon Hill, and those trays of maps and cardboard chits from… was it TSR? I bought a lot of them. Rarely played them. Then came to my high school the first L.A.R.P. (Live Action Role-Play) I ever encountered. I think, though I can’t swear, that it was called Chaos. Or Kaos? It involved stalking opponents through the hallways of the school and attacking them (theoretically, of course for these were math and science geeks doing the attacking.)

I don’t remember what form the attacks took. I do remember writing an editorial in the school paper about “Chaos.” We’d done a news article about it in the same issue. (I was the news editor for the paper.) I was somewhat disturbed by quotes from one enthusiastic player to the effect that the simulated killing was more of a rush than sex. This quote coming, I’m fairly certain, from someone who, at sixteen or so, had firsthand knowledge of exactly neither. (Nor, I quickly point out, did I have… much… firsthand knowledge of such things at the time either.)

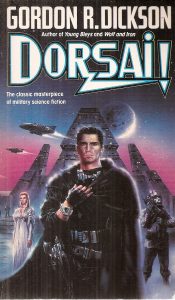

A friend on the paper was antagonized by my moral high-handedness. (Probably a fair reaction on his part.) Once he learned that I was one of those “don’t glorify violence” types, he began to taunt me by reading passages from his favorite science fiction novels which described violence. We had a running, fairly friendly rivalry going throughout the rest of our shared school careers. I particularly remember him telling me that I would hate the Dorsai series, because I was a lily-livered coward. For some reason, I must have taken him to heart, for I went another 30 years without reading a Dorsai novel. Probably not surprising, as I overall don’t care for military science fiction. While Robert A. Heinlein is, hands-down, my favorite author, and I recognize that Starship Troopers is a well-written novel, that book is, nonetheless, grandparent to a genre I don’t care for. I also found it made me too uncomfortable to want to read it again.

Why did it make me uncomfortable? Hmm. Interesting question. Perhaps I am a lily-livered coward. Lazarus Long was, too, and I never resented him for it. Seriously, though, none of Heinlein’s other opinion-laced works disturbed me. I think it was simply because Starship Troopers is a very realistic depiction of basic training, albeit dressed-up and fictionalized, and I recognize that the military life is not, and never will be, for me. Also, I am one who comes down firmly in the opposition camp when it comes to the suggestion, proposed in the book, that military service should be required before citizenship is awarded. To me, that’s just too close to a draft. I don’t know that Heinlein endorsed this system which he described, but I know he was opposed to the military draft. And I’m opposed to both of these methods of enticing people to serve.

Why do I call Starship Troopers the “grandparent” of military SF and not the parent? Most likely because I consider Dickson’s Dorsai! to be the parent, and S.T. the elder which inspired that parentage. That may seem an illogical conclusion, since Dorsai! was published first, serialized beginning in May, 1959 in Astounding, with S.T. following five months later in Fantasy and Science Fiction. I would defend my argument, however, by pointing out that Heinlein was being published regularly for nearly two decades before Dickson’s career began. I view most S.F. authors who began writing after the Forties as Heinlein imitators, and I do believe S.T. was a Heinlein novel which excited interest in the genre without being part of the genre, while Dorsai! is a prime example of the genre itself. It’s the same reason I wouldn’t say that Stoker’s Dracula is part of the vampire genre typified by Twilight, or that The Bride of Frankenstein is a “monster movie” in the vein of its later sequels.

So, I basically just admitted that I shied away from this book, that I don’t like the genre it’s a part of, and I’ve compared it unfavorably to a book by a more famous author, a book I also didn’t care for, despite its artistic merits. Why, then, am I writing this review? My goal (unstated, perhaps?) in these columns is not to take current works and say whether or not they’re worth your time. It’s to tell you about works I’ve encountered which are worth your time, even though they may not be marketed on the shelves of a local bookstore. That goal, I hope, prevents the tone of my missives from becoming too negative. I’m reminded (often) that I’m prone to be negative.

Well, I’ll tell ya… I’m reviewing it because I think you should read at least one Dorsai book, in the name of S.F. literacy. At the very least, you should know what a typical military S.F. novel is like. I also think Gordon Dickson is a talented author, even though I wasn’t thoroughly absorbed by this very early example of his work.

This novel breaks a lot of rules coming out of the gate. Now you know how I feel about rules. I said in the self-publishing diatribe a couple weeks back that you need to write them yourself. An artist breaks and/or makes rules, a technician follows them. I am therefore not offended by a novel that breaks the rules that have been laid down, telling authors how they must structure a novel. I do cast a sad, wry smile, however, when I reflect on how many rules are broken by novels that were published early in the days of the S.F. genre, and early in the careers of those writing them. It makes me wonder if those same novels would see print today, when many novelists are trained and expected to be mere technicians.

It opens with Donal Graeme, young son of a proud warrior family, walking through a spaceport and reflecting. Not an auspicious beginning. It has no action, no mystery, no demonstration of why we should feel sympathy or admiration for Donal… it has no hook. The first rule broken is a pretty good rule, and a pretty bad one to break: have a hook to catch the reader!

We then move into Chapter Two, in which Donal has dinner with his family and engages in the old world custom of retiring with his elder male relatives afterwards for liquor and “male” conversation. A lot is revealed about the essentially libertarian culture of the Dorsai world, but it’s too much all in one chapter, and it’s revealed by a big cast of characters. There are too many of Donal’s family in this chapter; they do nothing to distinguish themselves; so I didn’t find it easy to tell them one from the other. Consequently, their use as a device to tell me a whole world’s history was about as exciting as listening to a Greek chorus during a marathon performance of the Oedipus cycle. So, broken rule two, don’t put all the exposition in one block, and especially don’t stick it at the beginning of the book. Still, you see the author trying to break it up and make it a part of a lively dinner discussion. Maybe I just wasn’t in the mood for it at the time.

And rule three that’s broken is covered in the same chapter – too many damn characters! I get that Donal is part of a big family, but I don’t think it’s good storytelling to meet all of them in one scene near the beginning of the book.

On the other hand, it’s a good storytelling technique to start with a young protagonist who’s just coming of age. We can all identify with that. If we’re very young, we dream of coming of age. If we’re coming of age right now, we have a built-in sympathy for Donal. If we’re way past the time of young adulthood, well, we were there once and we remember it fondly. (Personally, I think I especially enjoy coming of age stories because, though I’m a whole young adult’s lifespan past young adult-hood… and then some… I feel that my life has been filled with “coming of age” moments, and they’re not finished happening yet.)

I think the part which makes the book most worth reading, though, is its depiction of an actual battle in space. The whole reason I picked up Dorsai! when I did is that I’d been asked to be on a panel at MystiCon called “Kicking @$$ in Hyper-Space,” in which four authors tried to come up with what made for a good space battle, be it literary, filmed or televised. I felt at a loss, since, apart from Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan, I couldn’t think of a good space battle, despite all the S.F. I’d devoured. I thought it was time I gave the Dorsai a try, and I’m glad I did, if for no other reason than Dickson’s handling of the Battle of Newton, one of the seminal moments of Donal’s career.

The description focuses entirely on Donal, his observations of what’s going on in his immediate surroundings, and his reaction to the events of the battle. There is no discussion of the weapons employed, nor even any description of the types of ships that are engaged in combat. These are not things that an office in battle would be thinking about, and so we are not exposed to them. We live the battle with Donal, and so see firsthand what it’s like to be that office on that ship. It’s a very personal account (although it is third-person), and thus is strong storytelling. When we reach the words, “The battle of Newton was over,” it comes as a surprise. Surely the end of the battle came as a surprise to Donal as well, caught up as he was in trying to help wounded friends. It’s the most powerful sequence in the book, and the reason I know Dickson is a capable writer, even though this book, as a whole, did not satisfy me.

I’ve been assured by friends who’ve read other books in the series that it does get more exciting, and particularly that the Dorsai includes some strong female characters. That explains to me why at least one of the four narrators of Heinlein’s Number of the Beast thought fondly of “the Dorsai yarns.” I can’t imagine any of Heinlein’s protagonists wasting his or her time on stories that didn’t satisfy.

One stray question I’ve been asked a few times I feel I should deal with here, since I’ve mentioned that I don’t care for military S.F. I answered it, in fact, on that “Kicking @$$” panel. That question is, if I don’t like the genre, why have I written nearly two dozen stories in the Arbiter Chronicles series? Isn’t it military S.F? Library Journal compared it to David Drake and David Weber’s works, and most reviewers class my stories as military S.F. I don’t class them so. I similarly don’t consider the original Star Trek, one of my inspirations, itself inspired by the adventures of Horatio Hornblower, which is another of my inspirations, to be military S.F. I don’t even consider Hornblower to be military fiction. To me, military fiction is about the military, military life, protocols, strategy and chain of command. Arbiter Chronicles and the series I loved which inspired me to write it are about people who are in the military. They are no more “military fiction” than Hill Street Blues was a police procedural drama. If you ever look to me for a good discussion of strategy or protocol, you’re going to come away sorely disappointed!