A while back, a friend of mine shared on his Facebook timeline that he had just confronted the problem of having civil discourse with some homophobic relatives. When I was growing up, it was pretty much standard issue to have an older relative, out of step with the times, who made judgmental and even bigoted comments at family gatherings. It was so common that one of the most-watched TV shows of the 1970s centered around such a character. Google “Archie Bunker” if this is ancient history to you. Trigger Warning: Archie says all the words.

I sympathized with my friend and was yet a little surprised when someone commented to the effect that he simply should not have anyone homophobic in his family circle. And the old observation that you can pick your friends but not your family came to my mind, as Harper Lee summed it up in To Kill a Mockingbird, “You can choose your friends but you sho’ can’t choose your family, an’ they’re still kin to you no matter whether you acknowledge ’em or not, and it makes you look right silly when you don’t.”

We live in intolerant times. One might say I grew up in intolerant times as well, hence Archie Bunker. I guess that’s true, but I feel American society at large has grown more, not less, intolerant. Instead of pitying the Archies of the world, who are, in the end, ignorant and frightened, not evil, we meet intolerance with intolerance, hate with hate, and we quote philosophy to back up our two-wrongs-make-a-right approach.

In past blogs, (here and here) I’ve made a appeals for tolerance toward those with whom we disagree. Both times, I was advised in feedback to have a look at Popper’s Paradox. I did have a look at it. I’ve never really shared my reaction to it. So here it is: I think Popper’s Paradox is a cop-out. Nothing more than an excuse to behave badly.

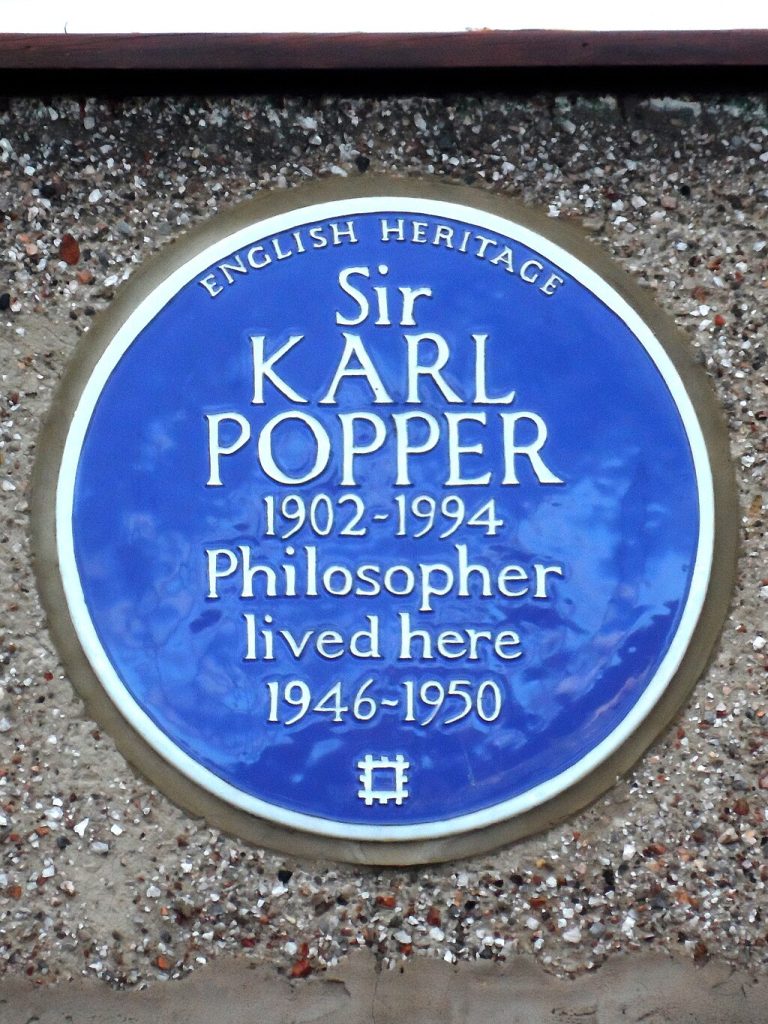

Philosopher Sir Karl Raimund Popper emigrated to England following Nazi Germany’s Anschluss (annexation) of his native Austria. He was an outspoken enemy of both fascism and Marxism, and a proponent of liberal democracy and an open society. In his 1945 work The Open Society and its Enemies, he posited the Paradox of Tolerance.

In his own words, “If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant… then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them.” By, “Intolerance,” he meant I assume any attitude which works against democracy or suggests that some people should be either excluded from the democratic process or denied full citizenship, as millions in Germany were so denied under Adolph Hitler.

He placed some limits on his proposed intolerance of intolerance: “I do not imply… that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument… suppression would certainly be most unwise.”

In his final analysis, however, Popper advocated that “We [the open society, in short, the elected government] should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; [emphasis mine] for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument.”

He goes on to say, in words very familiar to Democrats of 2024, that intolerant actors “may forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols.”

And so, he advocates, “We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.”

Those who invoke Popper’s Paradox (the informal name) as justification for shunning their political opponents have missed the intent of Popper’s argument. Popper was describing action which should be taken by duly-elected governing authorities, not individuals. Such actions, by their nature, could be challenged in court, weighed by competent legal minds, and possibly

struck down by judicial action. In other words, the power of any one party to suppress the speech of another would be subject to checks and balances.

I would also point out that Popper was advocating the control of specific, ideologically driven actions, not of people. A person who advocated government overthrow or race-based violence was to be prevented from spreading those ideas. He was not arguing that anyone who criticized a government policy or an elected official should be denied the right to speak at all, or that anyone we personally suspected of harboring anti-democratic opinions should be muzzled.

Still, for my own part, I cannot agree with Popper’s argument, even if limited to government action and subject to checks and balances. I recognize that incitement must be handled carefully, but I believe we as a society often go too far in applying incitement as a reason to suppress free speech.

My own feelings were well summed-up by Thomas Jefferson in his first inaugural address: “But every difference of opinion is not a difference of principle. We have called by different names brethren of the same principle. We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists. If there be any among us who would wish to dissolve this Union or to change its republican form, let them stand undisturbed as monuments of the safety with which error of opinion may be tolerated where reason is left free to combat it.”

The First Amendment promises safety–for all–in the freedom to disagree. And that freedom leaves reason free as well. This is the single-most important natural right protected by our Constitution, and we should guard it jealously. Making exception for “political extremism” is a dangerous game. Political Extremism, for most people, is just the belief system of anyone who disagrees with them. I’ve even had friends tell me that there are no extremists on their end of the political spectrum. Convenient, then, that if ideas are going to be censored, it will only be the ideas of “the other people.”

“But,” someone in the back row of the lecture hall of my imagination cries, “censorship can only be practiced by governments…”

As Frasier Crane notes in his new end credits, “Y’all know how this goes…” If you know me, you know that I do not accept that mewling argument. Freedom of Speech is a spirit, not just a law. It is the American spirit of free debate, of the marketplace of ideas. If your life is lived in an echo chamber of your own ideas, you are not personally living the American Dream, not matter your material success.

There are hateful ideas out there. There are people who are toxic to us. In the end, we each have to decide who we want in our lives, with whom we do business, what ideas we want to hear. But meeting hate with more hate only winds up hurting us, because hate eats away at your soul. Just as denying others the right to speak eats away at our freedom and our strength. Shut your ears if you need to, but, please, don’t cop out and try to make our society free only for people who think like you.