Note: If you haven’t seen the film, take my word for nothing in here. PLEASE see it and draw your own conclusions. It’s still running in 65 theaters around the country.

Note: If you haven’t seen the film, take my word for nothing in here. PLEASE see it and draw your own conclusions. It’s still running in 65 theaters around the country.

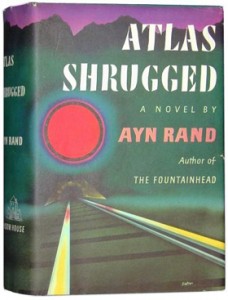

Continuing my review of Atlas Shrugged: Who Is John Galt, I wish to pause for a disclaimer and a shout-out. First, the disclaimer: I am speaking frankly about this film because I believe in the project. I respect the passion of the creative team behind it. I understand the obstacles they had to overcome to bring an overwhelmingly popular book to film under the eye of a film industry that largely holds its audience in contempt, and believes that this book is only popular because most of the reading public is too stupid to know what’s good for them. I admire their effort, and I hope it will ultimately pay off.

The shout-out is to Harmon Kaslow, producer of the trilogy, who also co-wrote the screenplay for this latest entry. After I posted the first part of this review, Mr. Kaslow was gracious enough to email me and let me know he’d read it, and that he thanked me for posting it. It takes a big person–someone with a strong ego, perhaps?–to thank a writer for his negative criticism. So my hat is off to him, and I hope he continues to see my comments as supportive of his efforts, for all that they may not be what he had hoped.

So last time I said there were some thematic issues with this third film, that its missing the heart of part three of the novel. Appropriately, I have three major issues.

The first is that this film lacks a powerful antagonist, or set of antagonists. That’s not to say that the parts of Mr. Thompson, the executive of the People’s State, or Cuffy Meigs, his obnoxious, pampered goon, or even wannabe rail baron James Taggart, are not well-acted. They are. But the actors had no control over the fact that some of the story points which made them credible villains were missing.

In the film, we’re shown, near the end, something called “Project F.” Project F looks pretty much like an oscilloscope on an equipment card, connected by jumper cables to a metal grid. It’s used to apply electrical shocks to a victim in the name of torture. It’s supposed to be a great leap forward in technology, but it looks like something a sadistic middle school student could build in his basement. It apparently almost kills hero John Galt, and, y’know, electrical current will do that. But it doesn’t look like a technologically overwhelming weapon. It doesn’t look like it should be that big a secret. It certainly doesn’t look like something that would serve as an ultimate weapon so that an gang of dull, unimaginative thugs could potentially snatch the world away from their more-gifted brethren.

And, to be fair, Rand both created Project F and wrote the torture scene at the end of the film pretty much as it plays out on film: John refuses to become a figurehead leader, Mr. Thompson orders him tortured (so that he will agree to be a figurehead, but this isn’t made clear), his friends rescue him. But Rand wrung far more suspense and emotion out of the printed word than this film does out of a piece of 1960s technology on an antique cart, sitting in an abandoned warehouse. She made the reader believe John Galt’s life was in danger. The film does not.

Indeed, even the other characters don’t seem to believe that John is in danger, for their reactions during the rescue are not as ruthless as are those of their literary counterparts. Case in point: Rand carefully describes the scene in which Dagny Taggart confronts a guard who is blocking her access to John Galt. The dialogue in the scene is very close to that in the book. The actor playing the guard does a good job of demonstrating how ugly it is when a human surrenders all his reasoning power to the mob, and decries that he was never told he might have to make a decision, and it’s not fair. But Dagny’s response to his indecision, which is to shoot him, is robbed of its power. Rand describes the shooting like this:

“Calmly and impersonally, she, who would have hesitated to fire at an animal, pulled the trigger and fired straight at the heart of a man who had wanted to exist without the responsibility of consciousness.”

In the heart. The heart! Dangy wasn’t screwing around. She was making a statement that, when confronted with such powerful evil, reasoning human beings cannot plead indecision. It’s fatal. She couldn’t risk being merciful, because this man was being complicit with people who had no mercy for anyone. Project F was merely an afterthought, a symptom of their cruelty. It was the men they faced who were the grave threat, because there was no moral limit to how they would use their stolen technology. Nor did they place Project F in the middle of a busy city with only one guard to watch it. It was out in the wilderness, with sixteen guards, four of whom our heroes must face directly before rescuing Galt.

In the film, she shoots the guard in the shoulder. He falls down without a sound. I guess because he couldn’t decide whether or not to scream. This was probably done to make Dagny seem less bloodthirsty. And, I must say, given the weak forces she was confronting, this Dagny in the film had no excuse to kill a man while fighting them. After all, all they had was “Project F,” and it could do little more then overcook a steak.

But Dagny in the book has every reason to be desperate and cruel, for the bad guys she’s up against do have a weapon which could take over the world. It’s the much-bigger “Project X,” described in the book and never mentioned in the film. Project X uses sound waves to destroy. Rand describes a test session with it, which levels a farmhouse in seconds, and leaves a live goat in the yard a bloody mess, a single, pulped leg sticking up amidst the wreckage. Project X is, in the words of Doc Brown, some serious shit. Indeed, it’s what levels the Taggart Bridge, what we’re told is one of the great engineering triumphs of the century. (In the movie, we’re told it fell to bureaucracy. Neat line, but…)

Without Project X, Thompson, Meigs, Mouch and Taggart are little more than Monopoly characters, sitting around the board room (literally) blowing smoke rings. (Also without Project X, we’re denied the emotionally satisfying death of Cuffy Meigs, a brute who had no right to breathe air that might be used to better purpose by others, as well as the tragic death of Dr. Stadtler, who allowed his genius to be co-opted by the wrong people.)

Weakness number two concerns the death of Cheryl Taggart, sister-in-law to Dagny and wife to James. Cheryl is a principal character in part three of the book. She marries Jim because she believes that he’s the one that built Taggart Transcontinental, that he’s a genius who creates wealth and employs thousands, that he’s a visionary who stands above the rest of the human race because of his ability. But Cheryl eventually learns that her husband is a fraud, that he wants to steal power and rob people of real ability, so that he can snap the spines of his rivals and rule. Cheryl realizes that it’s Dagny, not Jim, who is the person of accomplishment. She’s backed the wrong horse. And when she becomes noticeably unhappy, that horse runs into the next pasture and takes up with the detestable Lillian Reardon, because Lillian has “pull.” (Lillian is absent from the film entirely.) Cheryl, defeated, commits suicide.

We see Cheryl’s final, tortured days only in flashback, after we’re told in a newspaper headline that she’s already dead. What was a major plotline in the book becomes an after-thought in the film, just another way to demonstrate to us that Jim Taggart is not a very nice guy.

But Cheryl represents something. She represents innocent admiration, the valuation of the good, and the search for true love. Cheryl is pure and open in her approach to the world, and she represents how innocence, unprotected, is twisted and destroyed by the second-handers of the world in their quest for undeserved wealth and power. Short-changing Cheryl takes away, again, from the power of the villains. They’re not the monsters they could be, for they don’t devour fair, innocent maidens. They’re just kinda mean to them.

And there’s another who dies in the book, also tragic, also relatively innocent. This is Tony, “the Wet Nurse,” sent by the State Science Institute to play watchdog to Hank Reardon, to make sure that Hank toes the party line. Tony is only “relatively” innocent because he actually is complicit with evil. He accepts a job which has no positive value, and works to hinder Hank, a productive genius whose work output is beneficial to all around him. Tony mouths the words of the second-handers, telling Hank that there is no good, no evil, no black or white. There are only shades of gray. Hank calls him, somewhat affectionately, “Non-Absolute.” Hank is never unkind to Tony, but he works around him and makes fun of him. And Tony is baffled by Hank’s disregard for the rules by which the game is supposed to be played.

That is, he’s baffled until he’s confronted with the evil of those he’s been working for. When he’s enlisted to aid them in their scheme to smear Hank and take away his steel mills, Tony decides to stand and fight–literally. He makes a stand at the foundry against a mob of conspirators, come to fake an employee riot. He refuses to cooperate with their plan, tries to leave to warn others. They shoot Tony and toss him, expectedly to his death, from a great height onto a slag heap. Tony survives only long enough to tell Reardon what he’s done, and to die in Reardon’s arms, as Hank struggles to carry him to safety, weeping over him, kissing his forehead, and telling him he’s no longer “Non-Absolute.”

In the film, Tony is gone. We don’t learn that Hank has had someone he was growing to love as a son taken from him by the second-handers.

Tony’s reaction to Reardon just before his death illustrates a central theme of Rand’s work. It’s not just about virtuous selfishness, and it’s not just about Reason being all, and the mind being the most valuable commodity. Rand does not only write about the individual as a distinct entity. She very much writes about his relationships with others. Love, be it romantic or brotherly, she sees as the reaction of our rational mind to the virtues of another. And to Rand, “virtue” is dedication to one’s own ideals, one’s own happiness and one’s own creative output. A Rand hero is happy when he sees another person accomplish something through his own efforts, with his own genius as his vision. This is the love Dagny and Hank feel for each other, that Dagny and John Galt feel for each other, that Hank and Franciso feel for each other. It’s the love Tony finds for Hank at the end of his life, though it has been growing the entire time they’ve worked together. It’s a love Hank returns when he sees that Tony has arrived at a personal plateau of realization.

And I would argue that Hank felt love for Tony all along: the love of a parent who sees that a child has potential, even if he hasn’t reached it.

Cheryl and Tony are both victims of the same evil, and both tragically so; for they recognized the good, and were manipulated by the evil as a result. With them gone from the story, we do not see the final, ugly cost of a philosophy devoted to putting others first, to never developing one’s own abilities and working for one’s own happiness. For a person of accomplishment, a Dagny Taggart, a Hank Reardon, a John Galt, can love the innocent. A James Taggart or a Cuffy Meigs never can. To them, innocence is an insult, because it doesn’t believe in the dark, ugly world they dwell in.

And Hank is gone from the film as well. Without him, without his face-to-face acceptance of Dagny’s love for John, despite their existing relationship, without Hank actually giving his blessing in some way other than over the phone, Dagny seems like an attention-deficit floozy. When she says to John at the end, “You’re my forever,” you wonder how long forever is for someone who dumped her last lover on a few hours’ notice.

I think a lot of this could be salvaged. I’m not sure why the editorial choices that were made were made, but I do know that more footage exists. I’ve been told by some who saw the rough cut of the film that Rob Morrow’s Hank Reardon was originally more than a voice over. I’ve no doubt that Cheryl’s scenes were filmed in more depth, and I wonder if Tony’s might exist as well. Even if they don’t, is it too late to film them?

These are good filmmakers. They’ve done good work before, and I think they can turn this disappointing effort into more of a fitting sequel to its predecessors. I hope maybe they, or someone with their permission, might take another look at their hard work and please re-cut this film!

Maybe for the DVD? I mean, I’ve already paid for mine anyway. Hell, I’ll join another Kickstarter. Whaddya say, fellas?

I agree wholeheartedly. You’ve put your finger on the things that could make this film a worthy successor to the previous two, and it does seem as though there’s hope that some of those scenes exist. My guess is that they didn’t film Project X (but could do so easily), but did film more about Cheryl Taggart and Hank Rearden. I understand why they had to leave Eddie Willer’s tragic death out, although that, too showed that Ayn Rand understood love and loyalty, and it didn’t just have to be between industrial titans.