I’ve been accused of eliciting tears with some of my stories. I wrote this piece eight years ago, and I think it’s one of those stories. I didn’t share it before because It’s sad, and it might sound self-pitying. It also might result in my receiving a lot of “Dude, are you okay?” messages, not to mention recommendations for therapists. I assure you, I’m okay.

I offer this account, first to break a cycle of second-guessing myself and fearing everything I write will somehow backfire on me. Second, I aim not to dwell on the negatives of my life, but to add some depth to my overall story. I think, publicly, I’m a positive person. I accomplish things. I help people. A lot of people say I’m supremely confident. Well, I’m not. Not always. There are internal negatives there. And I think it’s important to know that we all have them. Finally, hope this story will help remind the reader that no human being is meant to be a tool. No matter how useful we are, we should be considered as people first.

And now, about this beagle…

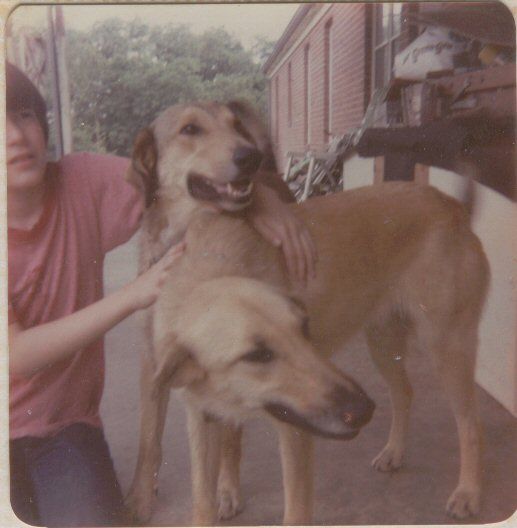

I guess I was twelve, maybe thirteen. We had two dogs—Benji and Lady—who were born in the Spring when I was nine. Lady would stay with us until I was in college, but Benji, well, he was an unaltered male. He wandered. Sometime around the Summer of ’78 he left us for good. Before he did, though, he brought home a girl from his travels. The girl was a beagle. She was a very nice dog, friendly and well-behaved. Personally, I wanted to just let her stay with us.

We had a problem, though. Lady was used to having Benji’s full attention. She didn’t want him to have a wife or a girlfriend or whatever the beagle was. But, as happens with dogs, someone’s the Alpha, and that someone made the decisions. That someone was Benji. He was married now, or engaged, or shacked up, or whatever, and his sister needed to make the best of it.

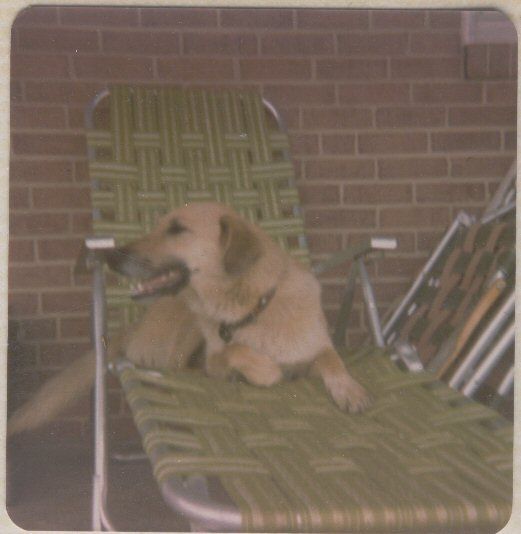

This ran afoul of my sense of fairness when the beagle decided she wanted a lawn chair. You see, Benji and Lady had lawn chairs—1960’s vintage aluminum lounges with nylon webbing. They had been purchased for humans, but, after all, Benji and Lady spent more time outside. It made more sense for them to use the chairs. So, when they weren’t chasing rabbits, groundhogs or each other (and Benji wasn’t away from home chasing tail), they were perched on their lawn chairs like an old married couple, surveying their domain and probably discussing, in canine, the foreign policy of the Carter administration.

The beagle being Benji’s guest, it made sense she would share his lawn chair. It made sense to me, anyway. The beagle felt she deserved her own chair, and that Lady should sit on the cold concrete from now on. Lady was willing to put up with this. When the beagle jumped on her chair and growled, Lady jumped down and cowered.

I was not willing to put up with this.

I liked the beagle, but I was going to be damned if my dog was going to be driven from her chair. So, when I caught the beagle bullying her, I scolded the beagle and chased her away. This resulted in the beagle being afraid of me. There were four adults in the house, but she was afraid of the kid. She just wagged her tail and cuddled everyone else.

You’ll remember that I wanted the beagle to stay. The other humans in the family disagreed. They didn’t want “that mangy animal” on our porch or in our yard. So they tried to chase her away. She wagged her tail and tried to cuddle them. That wasn’t accomplishing anything, so they started to call me whenever the beagle came near the house. “Come out and chase this dog away! It’s afraid of you.”

But I didn’t want to chase the dog away. I liked the dog. I didn’t want it to be afraid of me. I just wanted to protect Lady. I made this known to my family, but their response was always, “Come out and chase this dog away! It’s afraid of you.”

I began to feel like a weapon. I had no say as to whether or not I would be pointed at a target, and no say over the choice of targets. It didn’t matter that I wanted the dog to like me, it was useful to others that she did not.

Eventually, the beagle disappeared. Not long after that, so did Benji. I’ve often wondered if, because I was the weapon that was used to drive away his paramour, Benji considered me the enemy.

I’ve never forgotten that horrible feeling of being disliked, and useful because I was disliked.

Over the years, I’ve realized I never really shed the role of beagle-chaser. I’m told people are intimidated by me. I’m told I make people nervous. I’m told I make people feel stupid because I speak with confidence that I’m right. (I think that’s because I don’t speak unless I’m sure I’m right.) I don’t mean to do any of this. I know things. So what? Lots of people know things. I just know things that the majority of people don’t tend to know. Or care about. That makes me useful, but, apparently, it also makes me intimidating, untrustworthy, sometimes even unlikable.

But somebody has to know these things. Somebody has to have the confidence to speak up. It’s a role somebody always has to fill. That doesn’t mean that somebody should be a weapon, or that anyone should be afraid.

When I was 21, Lady was hit by a car and rescued by a passing driver. She was taken to the vet, who called us. She was alive and going to live, but she had a dislocated hip and a punctured lung. Because of the punctured lung, they couldn’t perform surgery on the hip in time. She would never walk again. Lady was a big dog, part collie, part hound. The vet said a dog that big couldn’t live without the use of her leg. We were advised to put her to sleep.

I disagreed, but I lost that argument. I was told I was being selfish to want her to live without quality of life. I get it now. I didn’t then. Of course, now, I’m told there are therapies that could have allowed her to walk again. I still understand where the rest of my family was coming from, then and there.

My family could not bear to watch while she was actually given the procedure. I didn’t want to watch, but I had to. So I held Lady on my lap while they gave her the shot. I hope she, at least, wasn’t afraid of me.

A final note, as you finish this. I’m not blaming my family for how I felt. They didn’t know. We often don’t know how others are feeling. That’s why it’s important to share our stories.