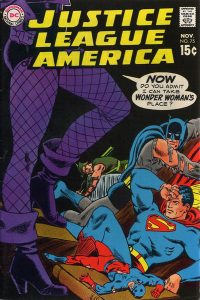

My wife Renee unearthed this issue, bought during my collecting days back in the late 1970s, in a chest of drawers in my mother’s dining room last week. I didn’t even realize it was missing from my collection, but I was happy to see it again. It’s in pretty good shape. Its cover is still glossy and its pages are not horribly yellowed. It was clearly a subscription copy, because, in the late 1960s when it was published, comic books were folded in half, lengthwise, before being mailed to subscribers. The comic book after market and CCG grading were unheard of.

My wife Renee unearthed this issue, bought during my collecting days back in the late 1970s, in a chest of drawers in my mother’s dining room last week. I didn’t even realize it was missing from my collection, but I was happy to see it again. It’s in pretty good shape. Its cover is still glossy and its pages are not horribly yellowed. It was clearly a subscription copy, because, in the late 1960s when it was published, comic books were folded in half, lengthwise, before being mailed to subscribers. The comic book after market and CCG grading were unheard of.

Despite the crease down its middle, it’s a pretty nice copy. I decided to sit down and read it, since it’s probably been 25 years. Indeed, I found tucked into it a K-Mart receipt from 1993, so I’m guessing that’s the last time I saw it.

This issue marks the induction of Black Canary into the Justice League. Wonder Woman having quit in issue 69, if memory serves, because she had lost her Amazon powers and wanted to be a plainclothes adventurer. With the JLA down its token female (the single female member of a super team in those days was wont to be referred to in narrative as “the distaff member,” “distaff” meaning “of or concerning women”) writer Denny O’Neill brought in a character who, ironically, was little more than a plainclothes adventurer herself to replace the no-longer Amazon no-longer princess.

O’Neill was something of a wunderkind at DC at the time. He had taken over Batman and would soon take over Green Lantern / Green Arrow. Under Denny, the characters ceased being pure, emotionless icons and developed more personality. Green Arrow became streetwise and hip, while Hawkman became the straight arrow cop, and the two didn’t like each other, which was unheard of for members of a super team until then.

He didn’t leave Black Canary a powerless adventurer. In this story, as a result of an encounter in the previous issue with Aquarius, “a star being,” she develops the power to throw supersonic blasts, a “canary cry,” or, as she referred to it throughout the 70s, her “sonic whammy.” He also didn’t leave the Canary single, even though her husband Larry had died in the previous issue. This story marks the beginning of her long-standing partnership with Green Arrow. The story leaves them both broken—Oliver Queen, the Green Arrow, having lost his fortune—and needing each other.

The hero-villain gimmick is that the Justice Leaguers, affected also by their encounter with the magical star-being, are manifesting duplicates which represent their dark sides. No one can touch these semi-ethereal beings except the person from whom they spawned, so the story must be resolved by having each Leaguer confront his or her darker side. A bit on the nose, but O’Neill was a young writer and not prone to subtlety in those days. Green Arrow’s confrontation with his opposite number is the only one that actually has the character dealing directly with his demons, and it contains a healthy dose of O’Neill’s trademark “Green Guilt.” He heaped it all over Green Arrow and Green Lantern during this period, and it’s a technique that doesn’t age well, for all the stories are considered landmarks.

Black Canary was an interesting choice for adding a new female member to the JLA. Hawkgirl had appeared only three issues before, and Supergirl and Batgirl had guest-starred. It was probably thought that female versions of existing leaguers wouldn’t be strong choices, and that a non-duplicative heroine (whom readers would know from years of guest appearances) would be better suited.

Dinah Drake Lance, the Black Canary, had first appeared in the Justice League as a member of the Justice Society of America, a precursor group from the alternate world of Earth Two, where the 1940s versions of Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern and the Flash still lived, albeit as older or retired heroes. The Canary was the youngest of them, having begun her career as a young woman in 1948, making her a decade young than her male counterparts, and probably close in age to Green Arrow of Earth One, whose Silver Age adventures would have begun around 1955, and with him as an already established industrialist, making him certainly close to 30. He was probably the older of the pair.

Which made it strange to me when, in 1983, Roy Thomas, Gerry Conway and George Perez decided to established that the Dinah who joined the Justice League was not the Black Canary of Earth Two, born c. 1930, but in fact her daughter, born sometime in the 1950s. Her mother’s memories had been transplanted into her brain after her father had died, and the elder Dinah had developed terminal cancer. Since Dinah the younger had grown up in suspended animation as a result of a curse by the super-villain The Wizard, she had no memories of her own.

This attempt to de-age the Canary and make her relationship with Green Arrow age-appropriate made sense from one perspective. The Justice Society’s origins were irrevocably tied to World War II, so they could not float forward in time, as the JLA did. So one of their members couldn’t just stay the same age as time passed on the JLA’s world. From another perspective, however, the de-aging doesn’t work. In two words, the problem is Dick Grayson.

Batman’s partner, Robin, became a superhero somewhere between the ages of 10 and 12. That was in 1940. By 1968, he was just graduating high school. Okay, so the early adventures of Batman and Robin are considered to have happened on Earth Two. With no formal announcement, sometime after 1955, a new Batman and a new Robin began their careers on Earth One. So Dick Grayson was now 15 years younger. By 1968, he had aged only to 18. By 1981, he was still in college, or at least dropping out of it. In 26 years, Dick aged at most ten years. Since he was just leaving for college when Black Canary came to Earth One, he could have been no more than 20 when it was decided she was decades to old to date Green Arrow. In other words, while her career had spanned more than three decades in the real world, she couldn’t be much more than 40 on Earths One and Two, even if you assume she aged “real time” from 1930 to 1968.

A little too much math? Maybe so. I think it’s just an illustration of how much it can take the fun out of things when fantasy characters are forced to conform too much to reality. It’s easier just to enjoy this issue, an artifact of a time when comics were starting to become a little more than they had been, and when a lesser-known Golden Age character started to become a major player.