There is much pontificating among science fiction media fans about how damned moral we are, because we watched these TV shows and movies that taught a moral lesson. Oh my God, we are so moral! Star Trek taught us not to be racist. Star Trek taught us not to be homophobic. Star Trek taught us that people who are different should be celebrated.

Oh, the cleverness of us!

‘cept…

Most of us have only learned, from Star Trek and other shows, the cleverness reinforced by the news media, our HR departments, and public policy enacted by certain politicians.

What I learned from Star Trek, and many other shows, was a lesson I don’t see evidenced in the attitudes or behaviors of a lot of people, not even fans. Maybe especially not fans.

I learned that people who disagree with me are not therefore evil.

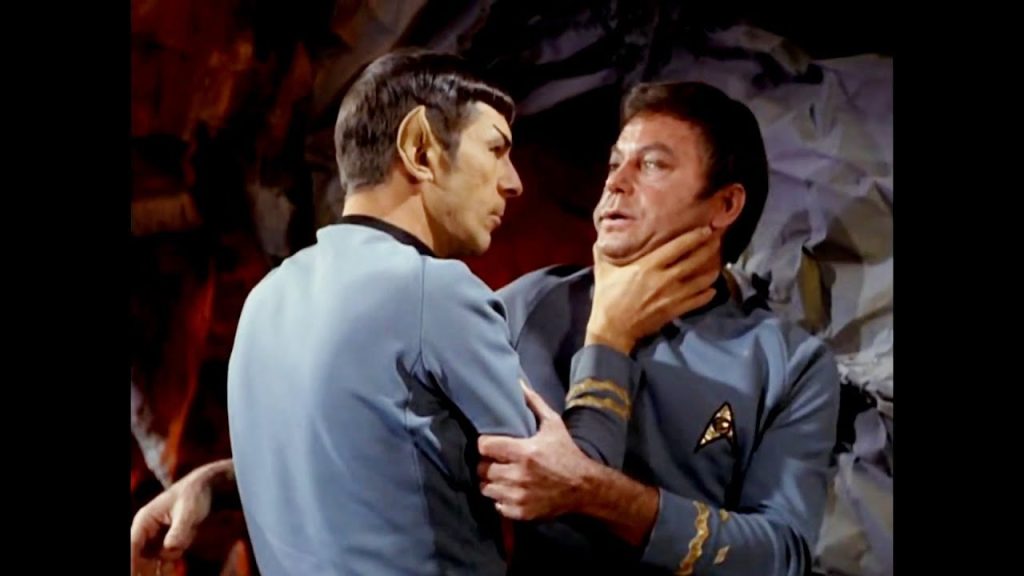

Star Trek showed me this, most immediately through Spock and McCoy, who disagreed constantly. Spock believed emotions were toxic. He characterized human civilization as reckless and foolish. He found us as warlike as Kirk found the Klingons. He clearly believed what his mother once came out and said, that the Vulcan way was, “a better way than ours.” For his part, McCoy was often enraged by Spock’s lack of passion. He also lambasted Spock’s whole race, calling him a “Pointed-eared hobgoblin,” and a “green-blooded sonofabitch.” News flash, kiddies: in today’s parlance, Spock and McCoy were both straight-up racists.

But Spock and McCoy were, on the balance, portrayed as good people, with heroic traits. They valued life. They fought to preserve freedom and the safety of their people’s worlds. They were friends, for all the harsh words they threw at each other.

The Horta, the rock-creature from the episode, “Devil in the Dark,” killed probably a dozen humans on a mining colony. These people had not pointed a weapon at the Horta or attempted to harm it, but it burned them alive, every time it found one of them. Understandably, the miners wanted the Horta dead. It was a dangerous animal, like the shark in Jaws. But then we found out why the Horta was practicing at being a serial killer: the miners were unwittingly killing her children.

The moral of the story was not, “Don’t hate people who look different.” The moral was, “Good people do bad things, and you really need to ask ‘Why?’ Sometimes they have a very good answer.”

The Klingons were so evil that they slaughtered civilians by the hundreds, especially in their first appearance, in the episode “Errand of Mercy.”

“In the courtyard of my headquarters,” Commander Kor said as the sounds of phaser fire echoed behind him, “Two hundred Organians have just been killed. In two hours, two hundred more will die, and two hundred more after that until the two Federation spies are turned over to us. This is the order of Kor.”

Sure, the Organians were energy beings pretending to be human. Kor wasn’t hurting anyone. But he thought he was. Kor committed acts that, in today’s media, would see him labeled a terrorist. When he was cheated of the right to wage war, Kor lamented that war “would have been glorious.” What is this, if not evidence of warmongering, of callous disregard for life?

Kor was not a lone wolf, not some kind of extremist. He was a quintessential Klingon. In time, as the Organians predicted, the Federation and the Klingons became fast friends. We saw it happen in Star Trek: The Next Generation. The Klingons were still warriors, still sometimes murderous. But they were also depicted as admirable, as having their own kind of virtue. Indeed, in the morally sterile climate of STTNG, they were the only really human characters to be found. They had real emotions and real flaws.

The takeaway? Even a culture whose morality appears antithetical to our own can not only produce good people, we might eventually look at that culture and recognize a mirror image of ourselves.

Mark Lenard, who played the first onscreen Romulan (before he played Spock’s father) came to the Shore Leave convention back when I was a teen. I remember him saying that he played that Romulan Commander, not as a villain, but as the hero of his own story. He played him as a decent guy who had a duty.

Our enemies often have their own code of morality. They’re not necessarily insane, much less evil for evil’s sake.

I didn’t only learn from Star Trek.

Will Robinson, on Lost in Space, once told his father, who was about to literally murder him, that he loved him. John Robinson had been possessed by an alien entity, and Will may or may not have understood that. He faced death bravely, and the only thing that mattered to him was that John knew that he was still loved. Because he knew that John’s actions were not all there was to John.

You can love people, even when they hurt you.

On Space: 1999, the Psychon Mentor tried to destroy the minds of the entire populace of Moonbase Alpha. When Mentor was defeated, the Alphans adopted his daughter, who still loved him. When she spoke of her dead father, no one shouted out, “You bitch! He tried to eat my brain! I require you to hate him if you want to be my friend!”

You understand and accept that you may not see lovable qualities in someone, but others may. That does not make those others bad people.

At the end of the original Star Wars trilogy, Darth Vader, the biggest villain in all of science fiction, is redeemed. He overcomes the evil influence of the dark side of the Force, rejects the corruption of nigh-absolute power, and gives his life to save his son.

The biggest villain of them all still felt love for his own flesh and blood.

The science fiction of my youth reinforced the cultural lessons of my family and community. Christianity taught me that we are all sinners. We all fall short of the grace of God. That doesn’t mean that we need someone to constantly oversee our sinful selves. It’s not an invitation to give up our free will. It means everyone makes mistakes. That’s how we learn. Yes, some flavors of Christianity also teach that one mistake condemns you to eternal damnation, but I never absorbed that lesson, nor did a lot of Christians.

I’m not saying it’s okay to say hurtful things to your friends, or that cultural relativity should be stretched to the point of tolerating murder and terror, or that fathers should be allowed to throw their children off cliffs or cut off their hands.

I’m saying bad actions do not equal a bad person. A different opinion does not equal evil. If you’re disposed to look at a person and say, “That person is evil,” then maybe, just maybe, you should put your disposition in timeout and look for the good in that person.

That’s what my beloved native mythology taught me. If you disagree, if you think that anyone who doesn’t pray to your sacred cow is an infidel and must be converted or destroyed, then, in the words of Charlie Brown, we are obviously separated by denominational differences.