Right?

I mean, I never met the woman. She’s been dead for 31 years. And what I’m mad at her about, she did when I was four. And it had nothing to do with me. Still, I’ve just never been so angry and disappointed with one of my heroes before.

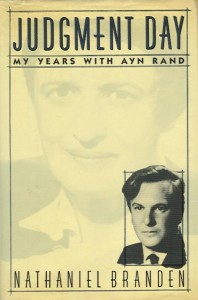

Okay, “I am so mad,” is an exaggeration. I experienced a moment of shock and anger is more appropriate. Let me back up a bit and tell you what prompted this. I was reading a book called Judgment Day: My Years with Ayn Rand. Since its original publication in the late 80s, it’s been renamed just My Years with Ayn Rand. Don’t know why. Was the original title too religious in its connotations for the atheist followers of Rand, or was it, perhaps, too subtle for the average reader to understand why what’s essentially a tell-all book (albeit a high-brow tell-all) would be named “Judgment Day.” Hint: It’s because Ayn Rand was noted for saying, “Judge and prepare to be judged” in answer to the Christian admonishment to “Judge not, lest ye be judged.” She didn’t think anyone should go without having to answer for their actions, so every day with her was Judgment Day. I guess it was kinda uncomfortable for a lot of people.

If you follow me on Goodreads, you probably know I’ve read a lot by and about Rand, especially lately. Well, I like to read about people I admire. I like to know about their lives, their struggles and their creative processes. I also read a lot about Frank Capra, Thomas Jefferson and Robert A. Heinlein, not to mention Jimmy Carter. (Gauge my politics with that list, bitches!)

I knew that Nathaniel Branden’s book might be an uncomfortable read. After all, Branden is the man whom Ayn Rand once named her “intellectual heir,” to whom she dedicated her greatest novel, and with whom she had an affair, although Branden was 25 years her junior. After nearly two decades of friendship, love and professional relations, the two fell out when Branden admitted to Rand that he did not wish to be her lover, and preferred someone closer to his own age.

I was not prepared to discover that I actually kind of like Nathaniel Branden, at least I like the image he presents in his book. He and I have a lot in common, including a tendency to feel alienated even among close friends, and a tendency to put so much of our emotional selves “out there” in public, that we tend to carry a chip on our shoulders inscribed, “What the hell more do you want from me?!” when we’re not making an “on stage” appearance. I’d like to think that I could not be convinced, even by someone I admired, to enter into a sexual relationship with them if I was not attracted to them. That’s just a bad plan on so many levels. And I’d like to think that I would not be the high priest in a very dysfunctional cult, where allegiance to the goddess incarnate trumps even the intellectual and moral foundations of the belief system.

But it didn’t happen to me, so I don’t know. I just know that the actions Ayn Rand took in severing their personal and professional relationship made me angry. Hey shit happens, and I usually don’t take sides in someone else’s argument, especially one rooted in a romantic relationship. But Branden gave an account of how Rand not only demanded that he turn over all interests in the two corporations he’d founded and operated for her with no compensation, she also demanded that he remain silent while she launched a public attack on his character, and she refused to give him copyrights to his own work which she had promised. The kicker was, on top of all that, she told him she had a man on standby, a brown belt, prepared to force Branden to sign a papers to the above effect. It was that last bit that made me slam down the book and shout, “What?” The woman who said that it was immoral to live for the sake of others, to ask others to live for your sake, or to ever initiate the use of force, was prepared to use force to take intellectual and real property from a friend?

The anger only lasted a moment. It was quickly mitigated by my realization that this was Branden’s account. And while he seems like an honest, intelligent guy, no one can really help “spinning” a story to make themselves look good and their opponents look bad. Although to his credit, Branden makes a real effort in this book to say very, very positive things about Rand, this is still only his side of the story. There are probably those who would dispute some of what he presents as fact, and I can’t say one way or the other. Here, I’m just recounting his description of events.

But the anger was… intense. It was fueled by extreme disappointment. I wouldn’t have cared if, say, Hemingway or Fitzgerald had done something dirty and underhanded to their friends. But they didn’t help advise me on what morality is all about, and Ayn Rand did.

Knowing this, knowing how colossally she at least once fell short of her own standards, do I think that means her philosophy was wrong? No. Because people with great ideas, I mean, really great ideas, can’t help but be smaller than their beliefs. That’s the wonderful, amazing paradox of being human. You’re flawed, you’re imperfect… you might be a downright asshole. But, as the High Lama says in Lost Horizon, “There are moments in every man’s life when he glimpses the eternal.” And that glimpse of the eternal is often a helluva lot bigger than the person doing the glimpsing.

What’s the saying? “Idols often have feet of clay?” Yeah, I guess it’s true. Our heroes, if we get too close to them, might let us down by turning out to share failings with “just regular folks.” (An expression and a class of people Rand really resented. She thought people should aspire to not be “just regular.”) It can be rough to deal with. Does that make them less heroes? No. Not for me. For me, my heroes are on their pedestals because of the great gifts of ideas they left mankind. Thomas Jefferson owned slaves. That can be rationalized, but it can never be excused. But he also helped make generations of Americans (and many others) understand what freedom is supposed to be. No amount of human failing on his part can ever take that away.

But those human failings sure look bigger, cause more hurt, and instill more anger when we see them in people who should, in our eyes, be better than we are. We need to learn that it’s not the people who are better than us, it’s their ideas which are bigger and better than those of everyday people.

Would I have liked Frank Capra? I don’t know. I’ve read a lot, but I don’t have a sense. Would I have enjoyed walking the grounds of Monticello with Jefferson? Not sure. Would Bob Heinlein’s foibles have made me roll my eyes? Maybe. Would I like Jimmy Carter if I sat down and talked to him? (Actually, I really think I would.) The point is that it’s not these people’s personalities that are as important to me as the works those personalities drove them to create.

Still, I wonder again, reading of how Ayn Rand could emotionally bully those around her… How would I have reacted to her directly? A lot of her followers seemed to subjugate their wills and intellects to her. They seemed to live in mortal fear of angering her. I have a long history of shouting obscenities in the face of people who try to bully me or who constantly judge me. I have a reputation for standing up to people.

But…

I also know myself, and I know that I have, often in my life, allowed myself to be emotionally bullied. I let people make me the bad guy. Some people that I’ve really cared about, whose admiration I really wanted, have been able to maneuver me into an inferior position, morally, ethically or politically, because I have tendency to question myself and my motives. I try to meet everyone halfway, so, if someone I care about says, “You’re 100% wrong,” they tend to get immediate 50% buy-in from me.

Would Ayn Rand have done that to me? Maybe. I like to think that, like Branden, I could have broken away if she had. And yet I can summon the faces of a lot of people about whom I now think, “Why did I let him/her treat me that way? Say that about me? Make me into the bad guy when I wasn’t?”

Because, I guess, as Branden notes in this book, deep down, we all have a need to admire somebody. And when we pick someone to admire, we make ourselves vulnerable. We give that person, if we know them, power over us. And power corrupts.

I’d still like to continue meeting people I admire. It doesn’t happen too often. I’m willing to take the risk.