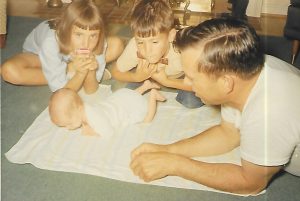

My Dad isn’t here to spend Father’s Day with me. He died on May 6th, at the age of 94. This past Tuesday, we buried him in his native North Carolina mountains, after a funeral at which I delivered the eulogy. So, in honor of Father’s Day, here’s what I decided to tell people about my Dad:

The topic of today’s lecture is Snell’s Law. Snell’s Law describes the relationship between the angle of incidence of a light wave as it passes through a transparent medium, and the resulting refraction of that light. Which is a fancy way of telling you why sunlight looks different when you see it from the bottom of a swimming pool–because the light comes through water and twists and bends before you see it. Which is another way of saying that the way things look depends an awful lot on what you’ve come through before you see them.

Col. Charles Edwin Wilson Sr., US Air Force Retired, Physicist, Engineer, Teacher and researcher… my Daddy… came through a lot. And it definitely shaped how things looked to him.

My father did not, as a rule, drink alcohol. He certainly was not a cocktail party kind of guy. But he did have an opening line for starting conversations at parties or other social occasions. He would invariably ask new people that he met if they were familiar with Snell’s Law. He would ask this of engineers, of medical doctors, and, perhaps most baffling, of girlfriends and other friends that I brought into the house. I guess it was his litmus test for determining if people were educated, critical thinkers. Or, to put it in his terms, if they were aware.

In my father’s eyes, it all came down to awareness.

And he was aware of everything around him. Learning about the world, what was in it, how it worked, and why it worked the way it did, was his passion from the time he was born. And learning didn’t always mean going to school, which is partially why he was held back four times, and didn’t graduate high school until the age of 20. He was too busy staring out the schoolroom windows and dreaming about what he could discover in the world beyond them. In fact those dreams led him, two years running, to simply fail to return to school after Christmas break.

But, frustrated as he obviously was with school, Ma Wilson told me that he was about seven when he announced to her, “Mama, when I grow up, I’m going to college.” She said it broke her heart to have to tell him that they didn’t have money for things like that. But money was never much of an object to my father. Thanks in part to his service in World War II, and in part to a service station he bought in partnership with my Uncle Wyman Higgins, he went to NC State for a bachelor’s degree in Engineering, and later to Drexel for a Master’s. He told me often that his work at Johns Hopkins through the years would have qualified him for a doctorate if he’d had time to assemble and defend the dissertation. I don’t doubt it. Two things I know about my father: he could work like a mule and he was always running out of time.

His commitment to learning extended to his children. He was always meeting with our teachers and principals. He drilled us in English grammar and history when we were on road trips. He taught me binary arithmetic before I learned my multiplication tables. And none of us for a moment considered college to be optional. We. Were. Going.

Nor did he limit his teaching to reading, writing and ‘rithmetic. He taught us folk songs. He told stories. He loved to tell stories. He would get so caught up in talking to people that it would take him hours to get to the other side of any door. I think he just didn’t know how to say “goodbye.”

In fact, I’m sure of it. He never said “goodbye” when we ended one of our many, late-night phone calls. He always said, “We’ll see you.”

He didn’t behave the way other people did, or look at things the way other people did. Which brings us back to Snell’s Law. It all depends on what you’ve come through. Edwin Wilson came through the Great Depression. He came through a move from a big city–Toledo–back to his rural birthplace, Pensacola. He came through three wars, serving in all of them. He was called back to a training assignment during the Korean War because of his teaching ability. He was sent to fly over the Ho Chi Minh trail in Viet Nam because of his brilliance in developing solutions to problems.

He could look at just about any piece of equipment, figure out how it worked, and then come up with a way to make it work better. Sometimes, as in Viet Nam, that was a dangerous proposition. And that ability was always with him. At the age of 21, he was on the crew of a B29, which had just bombed a target in Japan. The bomb bay doors didn’t close. With the doors open and dragging against air, his plane wouldn’t have had the fuel to make the hours-long flight back to its base on Tinian. Faced with the possibility of having to ditch their aircraft, he and his crew formed a human chain, hanging out of the bay, to grab the doors and pull them shut. They made it home. And, once they did, Daddy immediately climbed into a crashed Japanese plane, cannibalized its electrical system, and built a better system for closing his bomb bay doors.

His CO was furious with him for sabotaging government property–until a team from the engineering corps came to see this new system with an eye toward outfitting all their planes with it. This young man, until he was a very old man, knew how to fix anything. Even in his hospital bed during his last days of life, he was recommending to me a better way to hang doors. And it was better.

My father never gave up. To his dying day, he fought. He fought tyranny, he fought inefficiency, he fought bureaucracy, and he fought death. Lots of things slowed him down, not the least of which were Alzheimer’s Disease and a bad heart valve. Nothing stopped him.

Did death stop him? He didn’t expect it to. My father believed in life after death. I remember him sitting in his parents’ living room, telling Ma and Pa how thoughts were just energy, and energy is never actually destroyed. He said that the right receiver could still pick up George Washington’s thoughts, out there in space. I believe he was defending, scientifically, Ma’s passionate love of ghost stories.

On that subject, I want to tell you a story that my mother asked me never to let my father hear. I can’t promise he won’t hear it as I tell it now, but I’m pretty sure I’m on the good side of the statute of limitations.

In the Spring of 1989, I received a phone call from Ma, my grandmother, the one who loved ghost stories. Students of family history will note the date. I should have known something was up, because this call came in the middle of the day, and Ma always called late at night.

“How are you, Ma?” I asked her. “Pretty good,” she said. We talked for a while about what I was doing, and then I remembered something. “Ma,” I said, “didn’t you die a couple months ago?”

And she said, “Uh-huh.” Very cheerfully. I said, “Then you shouldn’t be calling me.” And she said, “Well, I just wanted to let you know that I’m all right.”

And then of course I woke up. Students of family history will have seen that coming.

The fact that I was dreaming does not, even for a minute, weaken my resolve that my Grandmother called to tell me that she was all right. She did, and she was. I know that. And now her eldest son is with her. I know that too. I just can’t explain the science to you as well as he could.

An atheist would tell me that my belief in an immortal soul requires the acceptance of an all-powerful god, whom no one can prove exists. I would say back to that atheist that his belief that death is the end also requires the acceptance of a god, or at least of some very powerful force that no one can prove exists.

You see, to convince me that my father’s spirit is no longer out there would be to convince me that, somewhere, there’s a force powerful enough to make Charles Edwin Wilson, Sr. sit down and shut up. Forever. And I’m here to tell you that there ain’t no such animal.

So, if it’s all the same to the atheists and everyone else, I’m just going to say, “We’ll see you, Daddy.”

And then I think I’m going to wait for another phone call.

(Link to the funeral program produced by my cousin Rhonda at Yancey Graphics.)

Wonderful job Steven. Your father was an amazing person!

Thanks, David! Sorry to be so slow replying. As I hope to explore on this site in the weeks to come, activity on Simpson Road has been foremost in my life. It’s kept me from keeping up with other endeavors for a while!