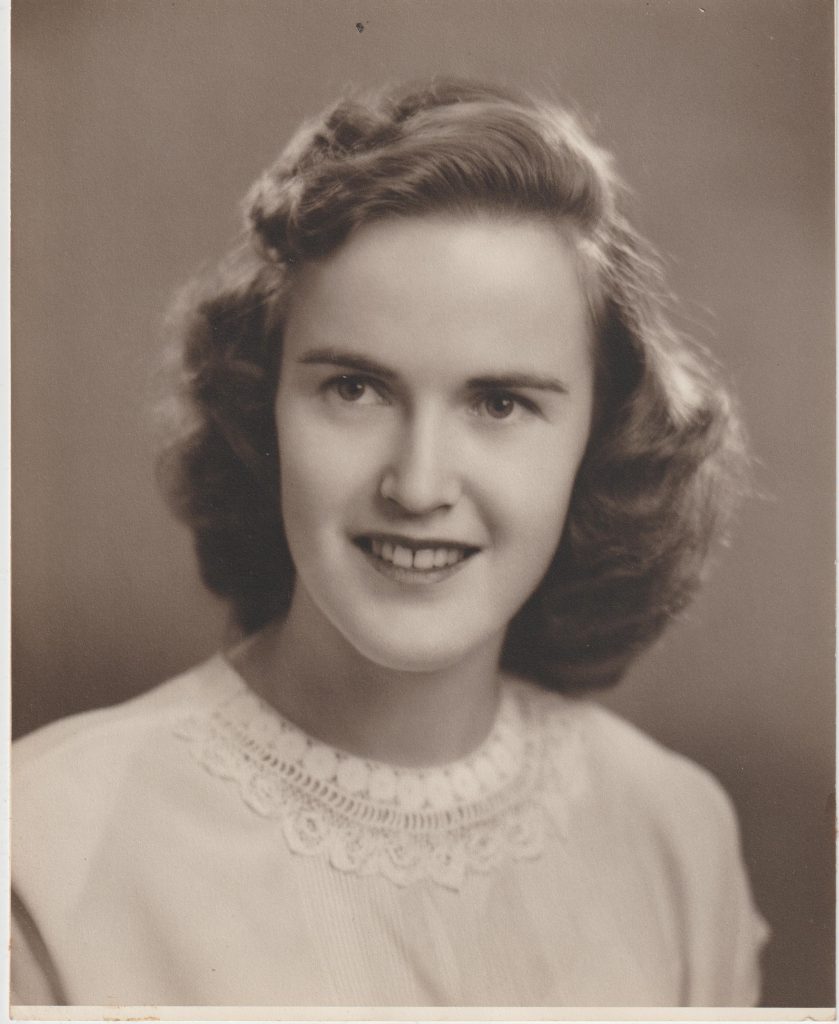

As with my father, I was asked to deliver the eulogy for my mother’s funeral. What follows is the text from which I worked last Saturday. I can’t promise that this is exactly what I said, but it gives the reader the general impression. And if you’re just catching up because Meta has failed spectacularly in the duty it assigned itself to be the principle medium of the communications of life events: My mother, Evelyn Briggs Wilson, born Elizabeth Evelyn Briggs on December 7, 1926, died on August 25 of this year. Her obituary related the facts of her life. And now for a more personal perspective:

Do you ever lie awake at night,

Just between the dark and the morning light,

Searching for the things you used to know,

Looking for the place where the lost things go?

Memories you’ve shared, gone for good you feared,

They’re all around you still, though they’ve disappeared.

Nothing’s really left or lost without a trace.

Nothing’s gone forever, only out of place.

Those words aren’t mine. They were written by a man named Scott Wittman for the Walt Disney film Mary Poppins Returns. It’s sung to children who have lost their mother. We saw that movie on Christmas Day in 2018, on one of our last Christmas trips to Rehoboth Beach, one of my mother’s favorite places.

The memories we’ve shared are all around us right now. Dementia changes people, but some prominent traits were with her to the end: her concern that everyone was getting fed, and that everyone had a bed to sleep in; her insistence that all the bills be paid on time–she was sure to the bitter end that she owed someone eight hundred dollars, and that her taxes were late. I never told her that the Maryland Comptroller had mistakenly sent her to collections this Spring for a tax bill she didn’t owe.

Her stubbornness persisted, as did that shriveling “Mother” voice. “Now, I told you I wanted to be left alone!” Unfortunately, she now used it to refuse being bathed and receiving medication.

We have to reach back across the years to recall some aspects of her. Mother was very organized–she was a librarian. Everything had a place and needed to be in it. Placing a library book on the floor–excuse me, IN the floor–was a capital offense.

Her sense of organization was tested by the life we lived in my childhood. Our house that was always under construction, and eventually devolved to a category six hoarder condition. She just carved out her own space–even if it grew a little smaller every year and became walled by banker’s boxes of junk mail.

She was intensely loyal to our unique family. Many people shook their heads, wondering how she tolerated us. She would defend us to the hilt.

She loved things she thought were sophisticated. One of my earliest memories is of her bemoaning, on a trip to the Smithsonian, that boys were unimpressed by a collection First Ladies’ gowns. The boys in questionwere my cousin Stuart and myself. Mother loved to read about lives and lifestyles of Presidents and Queens. I knew her focus was slipping when she lost interest in watching The Crown on Netflix. Princess Grace was an icon in our house, and Mother’s idea of a perfect day was a shopping trip to Lord & Taylor.

And, of course, she loved reading. We made weekly trips to the library and visited every bookstore we came across. In high school and college, I developed a passion for book collecting, and Mother was happy to encourage it. The two of us subscribed to a book catalog from a huge store in North Dakota. Every month I would clean them out of their film and TV novelization holdings, and she would put a considerable dent in their collection of 1940s mysteries. Leslie Ford was her favorite.

Mother liked things calm and simple. She did not like to inconvenience others, make a big fuss, or step outside her comfort zone. I tended to push that envelope. You may have wondered why there are pictures of a Colonial Wedding and an Iroquois raid in the memorial slide show. They’re part of a strong memory of Mother. They’re from the Wax Museum at Colonial Williamsburg. The museum itself is only a memory now.

It was Spring, 1977, and she, my father and I were staying at a Ramada Inn near the historic park. My dad had business in Norfolk, and we turned a business trip into a sightseeing one. We’d been to dinner, probably at the Visitors’ Center Cafeteria. Mother was a huge fan of cafeterias–the S&W in Asheville, the Hot Shoppe in Laurel. My dad had a night meeting, and he dropped us off at the motel while it was still light out. The wax museum was literally across the parking lot from our room, but Mother was tired. She wanted to get into her nightgown, read a book and watch game shows. I was… eleven. I was very eleven. I wanted to get out and do something. Mother said she’d never seen a wax museum, and I wanted her to see this one. Now, mind you, I wanted her to see it. There was no selfish motive at all, I’m confident. It was for her own welfare and continuing education that she needed to see this wax museum.

I talked her into going–with the understanding that, if she did not enjoy it, I would suffer tortures such as Lucifer and his minions never conceived. I avoided all the levels of the Abyss that night. She loved the wax museum, and she never stopped talking about how glad she was that I had insisted. She was gracious and did not use the words “whined” or “begged.” I was also gracious. For the rest of her life, I think I only said, “Wax Museum” to her about once a year when she didn’t want to do something.

Rehoboth Beach, as I mentioned, was one of her favorite places on earth. She discovered it when I was six months old. Relatives and friends recommended it, and Mother, who fondly remembered the Gulf Coast of Texas and was always conscious that her mother never got far enough from the mountains to see an ocean, was always up for a trip to the beach. The whole family fell in love, and it’s been our special place now for 57 years. It has changed, and so have we, but as long as her children and grandchildren live, it will be our special place because she introduced us to it.

The song goes on to tell us that

…when you dream you’ll find all that’s lost is found,

Maybe on the moon, or maybe somewhere new.

Maybe all you’re missing lives inside of you.

Mother carried inside her all that went missing along her path. They say Appalachians are natural storytellers. Some of us do it to excess. Mother didn’t. But she made her children feel as though we had known family members we never met, or that we’d known them a lot longer than we actually had. She was a bridge to the past. Her memories are inside us still, not missing at all.

I never visited the house where my Great Grandfather Banks moved his family after the Depression. I only saw Great Granddaddy and Granny Briggs’s house when it was abandoned and lonely. But I can see the meals being prepared in those kitchens, right down to the riced potatoes being cut. I can hear Mother and her aunts chattering during sleepovers with a half dozen of them packed into one bedroom. I know she was Aunt Cordelia’s favorite, even though I never met Aunt Cordelia, and I know that my Great Grandfather forgot my Great Grandmother had died, so the nurse parked a deaf lady in a wheelchair in front of him, and she smiled and nodded while he fussed at her.

I know that Mother’s parents got the first refrigerator in the community, and the children couldn’t wait to have ice cream from its mysterious depths. But my cousin Fred Young wound up crying because the ice cream out of the freezer was too cold. When Granny Banks was dying far too young, her parents sent her to stay with Jim and Nina Young. After a while, Mother decided that she was needed at home, so, without telling anyone, she left Jim and Nina’s and walked along the railroad track back to Granny Banks’s house. She was seven years old. Did I mention she had a mind of her own?

She hated doing laundry, because every day was laundry day. She and her mother would wash everything, then they would hang it out, then they’d take it down, and then they ironed. “We ironed napkins!” she would groan. But they took turns, so little Evelyn could take a break and read a book. She loved Elsie Dinsmore, a passion she shared with her best friend Doris. They would read Elsie’s adventures and cry and cry. As teenagers, they would listen to The Hit of the Week, and every weekend brought The Grand Ole Opry to the radio in the living room.

She developed a passion for movies early, and she thought she had reached the height of style when she and her parents dressed up to see Gone With the Wind in Asheville. It had an intermission, so you knew it was grand. She took Susan and me to see it for its 30th anniversary. I was three. I slept through the whole thing. For its 75th, the whole family went to the theater to see it again–possibly the first time that Evelyn, Edwin and all three of their children were in a movie theater together. And by that time, my father was the on squirming in the seat and saying, “Is it over yet?”

We laugh because It’s too easy to be sad that someone who brought us so many memories finished her life by losing them. After my father died with Alzheimer’s, Mother was very, very afraid that she would develop it too. It was only about a year before we saw the signs of a slightly different dementia. She tried her best to hold onto her memories and her mental skills, but they declined. She couldn’t process what she was seeing or hearing. My late daughter-in-law, Jessica, took care of her at first. Then Jess developed cancer and left us. I wasn’t sure Mother understood what was happening. But I recently found the little green notebook I’d given her so she could write down anything that was very important. All it contained were my phone number, Charles’s and Susan’s… and the dates of Jess’s surgeries and treatments.

In the end, she leaves us grateful. Grateful she could stay in the home that she and my father built. Grateful for our friend Carol Kelly, an angel sent down from Heaven, who lived with her and took care of her when she could no longer care for herself.

And we’re grateful for her memories. She lost them for a while, but now they’re all around.

So when you need her touch and loving gaze,

Gone but not forgotten is the perfect phrase.

Smiling from a star that she makes glow,

Trust she’s always there, Watching as you grow.

Find her in the place where the lost things go.

Cling to the memories….