I’ve mentioned the film Bell Book and Candle in my rundown of favorite holiday movies in the past. I revisit it now because it’s such an atypical Christmas film. I recall my mother taping it for my father back in the early days of VCRs, when some of us wanted to capture every film and TV show for posterity. We didn’t know YouTube was coming, or Netflix, or DVD collections of complete runs of TV series. One movie cost at least $40 then, and older films which hadn’t won Oscars or been box office smashes weren’t as quick to be released. Local TV stations were still showing movies then, albeit with large chunks missing to allow space for commercials. My family spent many hours sitting in front of the TV remote in hand, pausing for commercials, trying to get the most pristine copy we could.

I’ve mentioned the film Bell Book and Candle in my rundown of favorite holiday movies in the past. I revisit it now because it’s such an atypical Christmas film. I recall my mother taping it for my father back in the early days of VCRs, when some of us wanted to capture every film and TV show for posterity. We didn’t know YouTube was coming, or Netflix, or DVD collections of complete runs of TV series. One movie cost at least $40 then, and older films which hadn’t won Oscars or been box office smashes weren’t as quick to be released. Local TV stations were still showing movies then, albeit with large chunks missing to allow space for commercials. My family spent many hours sitting in front of the TV remote in hand, pausing for commercials, trying to get the most pristine copy we could.

Alas, those Betamax cassettes are all in boxes in the attic now. Eventually I think they’ll wind up as playground mulch.

But Mother’s comment as she cut the commercials was something to the effect of, “That’s the strangest Christmas story I’ve ever seen!” I guess it wasn’t a film she’d caught during the Fifties, despite its high-profile stars.

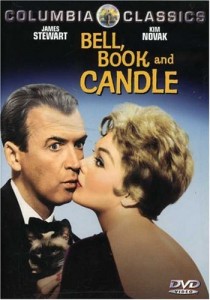

Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak headlined, fresh from teaming up for Hitchcock’s Vertigo. According to IMDB trivia, critics felt Stewart was miscast, and so did he. Cary Grant had lobbied for the role, but wound up with North by Northwest instead. Vertigo having been a box office and critical disappointment, Hitch felt Stewart was too old to play a leading man. Interestingly, Stewart was younger than Grant.

And my mother is right, it is a strange Christmas film. It’s not about Jesus or his birth in any way shape or form. Of course, lots of Christmas films are not about Jesus. I don’t believe he’s ever mentioned in Miracle on 34th Street or It’s a Wonderful Life (though Joseph and, Joseph’s boss appear as characters. I’ve never been sure who Joseph’s boss is meant to be. I assume it’s either Jehovah or St. Peter. He’s listed in the script as “Franklin.” Anybody know?) If Jesus is mentioned in A Christmas Story it’s only as a swear word. But of course “Miracle” is about Santa and “Life” is all about faith and hope and the Christmas spirit. And A Christmas Story… runs every two hours on TBS all day Christmas Eve. No, seriously, it’s about Christmas in 1950s Middle America from a child’s perspective. It’s about suburban life and ordinariness. It’s almost a foil to Bell Book and Candle.

Bell Book and Candle (the film’s title contains no comma, ungrammatical as that may be) shows Christmas trees and plays Christmas music. There is, I believe, a street corner Santa shown at some point; but it’s not about Christmas. It’s about how traditions and rituals accepted by the majority don’t suit every last one of us. Christmas is just a very easy example of one of our typical American traditions, which, in 1958, a lot of us were just beginning to realize was not typical for a large percentage of the American population.

The 1950s was about sameness. We had HUAC. We had Suburbia taking root. We were a nation victorious after World War II, but we were also a nation scared as hell of the power we’d used to (allegedly) win that war, the nuclear bomb. (Yes, I’m one of those. I don’t believe the nukes were necessary. The war was won. FDR and his sometimes-reluctant successor kept it going to achieve “unconditional surrender,” a case of political objectives being more important to politicians than lives, American or otherwise.) A lot of us embraced our sameness, probably because it helped us remember that we were on the winning side, the powerful side, looking out on a changed landscape that really wasn’t very pretty.

But some of us take pride and find strength in our individuality and our difference. We’d rather stand alone, or stand among a special few, and observe from the outside. We find comfort in the fact that we don’t have to carry our share of guilt for the sins of the majority. These are the kinds of people Bell Book and Candle is about.

John Van Druten’s play “Bell, Book and Candle” premiered on Broadway on November 14, 1950, five years and change after VJ Day. British-born Van Druten had emigrated to America before 1940. The original Broadway cast was headlined by Rex Harrison and his then-wife Lilli Palmer. The play ran 233 performances, and then had an extensive national tour. The touring company’s production would star Rosalind Russell and later Joan Bennett. The film expands on the story, taking the setting beyond a single apartment, and adding several characters to a cast of five. In addition to Stewart and Novak, it features talent like Jack Lemmon and Ernie Kovacs, and fantastic character actresses Elsa Lanchester and Hermione Gingold. It’s a treat to see them perform together, especially now that only Novak and Bek Nelson, who played Stewart’s secretary, are still living.

I’m not sure if Van Druten had a particular interest in witchcraft or the US and UK’s shared historical paranoia over witches, but he successfully used witches as a metaphor for any misunderstood minority you might like–Jews, homosexuals, fans of the 1970s Dr. Strange movie… Gillian Holroyd and her family are loving, overall moral people, who sometimes act a little silly and tend to be broke. In those ways, they’re like most Americans. But they’re also witches. They know how to cast spells. They can turn all the traffic lights on 42nd Street green. They can summon any person in the world into their presence. (The person has to use mundane human transportation. He doesn’t magically appear. But he has to come to them.) They can make a person fall in love.

Gillian makes publisher Shepherd Henderson fall in love… with her. Trouble is, the price of being a witch (in Van Druten’s work) is the loss of true human emotions. Gillian can’t fall in love. She can’t even cry. Her Aunt Queenie (played by the wonderfully wacky Lanchester, who, as the original Bride of Frankenstein and the wife of Charles Laughton knew her outcasts) observes that love and marriage to a mortal is just not done, but “hot blood” is allowed. (Although the term “mortal” is used to refer to non-witches, there’s no implication that witches are immortal.) If a witch falls in love, though, she loses her powers.

Gillian makes publisher Shepherd Henderson fall in love… with her. Trouble is, the price of being a witch (in Van Druten’s work) is the loss of true human emotions. Gillian can’t fall in love. She can’t even cry. Her Aunt Queenie (played by the wonderfully wacky Lanchester, who, as the original Bride of Frankenstein and the wife of Charles Laughton knew her outcasts) observes that love and marriage to a mortal is just not done, but “hot blood” is allowed. (Although the term “mortal” is used to refer to non-witches, there’s no implication that witches are immortal.) If a witch falls in love, though, she loses her powers.

Outsiders do pay a price for being different. Like Gillian, they can’t participate in the every day festivals and traditions as easily as can the mundane person. Like Gillian, they probably wonder what it would be like to not be different, as she observes, “To just spend Christmas Eve in some quiet little church, listening to carols instead of bongo drums.”

Why can’t Van Druten’s witches love? For me, it’s because, to live apart from the every day mob is to mute passion in a lot of ways. I think of the Society of Friends, the Quakers, who live apart in many ways–“In the world, not of it.” Their worship services are largely conducted in silence and contemplation, an atmosphere of calm, instead of the loud, rapturous cacophony of so many other faiths. Indeed, loudness and induced passion is a characteristic of tribal religions, meant to bind people together as a collective. Music, dance, loud, rhythmic sounds, can be trance or frenzy inducing, and they’ve been used by religions since before Christianity, Judaism or Islam developed to encourage and channel passion.

To not be tribal, to not be part of the crowd, is to govern and even distrust passion.

Christmas is largely a secular holiday now, but is still rooted in religion. Religion, by its nature is about passion, not reason. Gillian, who considers herself selfish and manipulative, feels like an outsider when Christmas comes. She’s curious about it. Aunt Queenie tells her that she wouldn’t like normal people, “They’re ordinary… humdrum.” But then she realizes her niece “might like to be humdrum with that Mr. Henderson.” Gillian might like to experience passion, even if it means giving up being different and special. This is breaking the rules. Gillian is supposed to accept Shep’s fake love and tolerate him only as a slave. She wants him to really love her. She doesn’t want to play by the rules. She breaks them even more, too. She actually tells Shep what she is and what she’s done to him.

When all this is said and done, Gillian is rejected, not only by Shep, but by both groups, humans and witches. Shep pays blackmail money to another sorceress to remove the love spell, and Gillian, who has really fallen in love, loses her powers. Her brother and their community have no sympathy for her. She tried to be different. Even in the elite group of the special, there is an orthodoxy. An individual still can’t break the rules.

When all this is said and done, Gillian is rejected, not only by Shep, but by both groups, humans and witches. Shep pays blackmail money to another sorceress to remove the love spell, and Gillian, who has really fallen in love, loses her powers. Her brother and their community have no sympathy for her. She tried to be different. Even in the elite group of the special, there is an orthodoxy. An individual still can’t break the rules.

By chance (or by Queenie’s meddling?) Shep comes back to Gillian one day months after their breakup. Her African art store, which looked bizarre and occult, has transformed into a seashell shop. Gillian has stopped dressing in black Capri pants and now wears a brightly colored dress, a pretty girl, not a fascinating femme fatale. Shep realizes she’s human, realizes it means she really loves him, and realizes he’s actually in love with her, spell or no spell. Was it real all along, he wonders? “Who’s to say what magic is?”

Gillian cannot control what she’s set free. She’s not the passionless, calculating manipulator she thought she was, but she’s something better, better than most people, better than most witches. She’s someone who stands on her own and tries for what she wants, even if no one is willing to help her get it. In becoming human, it initially looks like she’s sacrificed what makes her special. But she’s still an independent businesswoman (a rare thing in the 1950s), and she’s still a woman Shep finds worth loving. She’s still special. She’s just separated from yet another collective, a smaller one, but still one which makes rules on how to behave and, to some degree, prevents her from being what she chooses to be. She’s done it without completely joining the bigger mortal collective, though. She’s surviving on her own terms, learning what it is to be in touch with her emotions.

Who’s to say what magic is? I say that it’s a human being, discovering that she can think for herself and that she doesn’t have to be what any other group or individual tells her to be. Gillian is an individual. That sounds pretty magical to me.