Last week, I wrote about a famous man who had died: Leonard Nimoy. It was a gently chiding piece about name-dropping, and about how you don’t need to personally know a celebrity for him to have a huge effect on your life.

Last week, I wrote about a famous man who had died: Leonard Nimoy. It was a gently chiding piece about name-dropping, and about how you don’t need to personally know a celebrity for him to have a huge effect on your life.

And this week, because I’m nothing if not contradictory–or is that everything if not contradictory?–I’m writing about a famous man who died, and how the fact that I knew him personally intensified his effect on my life.

This week, sadly, I’m writing about Harve Bennett, who died Feb 25th at the age of 84. He was about the same age as Leonard Nimoy. They both had long careers in the film business. They worked together on a number of projects. They died within days of each other.

Harve had a career that spanned six or seven decades in Hollywood, starting as one of the Quiz Kids on radio, and going on to produce iconic 70’s TV series like The Mod Squad, The Six Million Dollar Man, and The Bionic Woman. For kids my age, the adventures of Steve Austin and Jaime Sommers were a promise of the miracles of technology, and an exploration of how wild and dangerous our world could be. And thrown in the mix was the obvious belief that human beings were competent, and could handle the danger and master the technology. That was Harve Bennett’s world in a nutshell. Hell, that’s science fiction in a nutshell.

Oh, yes, there are dystopian pieces which show the human race going to hell because they couldn’t handle their technology. A lot of people get off on that kind of hopelessness. I’ve never understood why. But that wasn’t ever the kind of story Harve told. Even in Star Trek IV, a tale with an environmental message which Harve co-wrote with Nicholas Meyer, his heroes used technology to undo the damage done by humans as they’d climbed the technological ladder. The moral wasn’t, “Humankind is an evil disease in the universe, and its technology is destructive;” It was, “Humankind can make mistakes while developing technology, and Humankind can also fix those mistakes, with courage, intelligence and morality.”

Harve was an optimist. That’s why he was the right choice to save Star Trek when it was poised on the brink of pop culture oblivion.

After Paramount’s Star Trek the Motion Picture succeeded at the box office, but disappointed both critics and fans, Harve was tapped to produce a sequel with a substantially reduced budget under the auspices of Paramount Television. The thinking was that Harve knew how to make exciting television, Star Trek was really a television show anyway, and perhaps Paramount could relaunch a successful TV series from a property that didn’t make that great a movie.

The result, of course, was Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. Widely hailed as the greatest Trek film of them all, it’s a cinema classic, a great piece of filmmaking. Because of it, Star Trek became a successful movie series and spawned four sequel series. Harve Bennett was the man who set all that in motion.

Star Trek II, as I’m sure I’ve mentioned, touched off my own career in science fiction fandom, in writing and, ultimately, in podcasting. Before it came out, I had loved Star Trek. For years, I’d watched the show and read the books and thought, “I want to do that.” After seeing Wrath of Khan, I thought, “I have to do that!” More, because the film is such a great piece of storytelling, I learned by watching it, and realized, “I can do that.”

33 years later, I’m still doing that, still telling stories. Not in the great, big worldwide way that Harve Bennett did, but in a way that satisfies me. And, if those of you who’ve been so kind as to reach out to me are telling me the truth, a way that satisfies you as well.

Harve Bennett set all that in motion, too. And not just from a distance. About ten years ago, my friend author Terri Rioux got in touch to say that she was in touch with the legendary Mr. Bennett, and that he had recently asked her if fandom still existed. He’d been to some very commercialized, money-driven cons in the late 80s, and they’d turned him off. He wondered if that was how all of fandom had become, or if maybe there were pockets of fans who still loved Star Trek and science fiction and believed in their ideals. If there were, he wanted to meet them. Terri knew that my friends and I run a convention called Farpoint, and that it’s known for its non-commercial, friendly atmosphere. She hooked Harve up with us. He came for two of our conventions.

Now I’m very busy at conventions. I like it that way. I don’t usually take time out to see guest stars speak, because I can’t sit still for that long. But when Harve was giving one of his talks at his first Farpoint, I was lucky enough to be backstage. As he was getting ready to leave the stage, he stopped to thank the committee for this wonderful convention, and he said a lot of really nice things about Farpoint. Now Farpoint is very personal to me. I don’t run it any more, but, like Prometheus, it was my baby. I started it and guided it to adulthood. I’m very, very proud of it.

I don’t recall exactly what Harve said, but it was one of those moments of perfect validation, clear and absolute. The man who saved Star Trek and set me on the path I followed as an adult was saying that this thing I had built was a credit to fandom. As I recall, he actually said Farpoint had restored his faith in fandom.

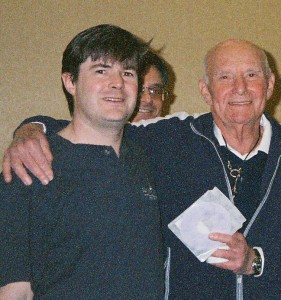

As he came backstage, I ran to meet him, probably baffling his guest escorts, because I rarely approach guests anymore. I shook his hand, and thanked him for his words. I said to him, “They tell me that this convention is here because of me. Well, you need to know that I’m here because of you.” It was just one of those… moments. Harve gave me a big hug. Pictures were taken. We’d established a friendship that meant a lot to me, and I hope it mean at least a little to him. I think it did.

Harve was not the kind of convention guest who hid in his hotel room. He came to the radio shows Prometheus performed. He did an interview with us. He and his lovely wife, Jani, even attended our production of Batsalot, a Batman / Monty Python parody, written by my then 13-year-old son Ethan. They enjoyed it so much they asked for two copies of the DVD.

A few years ago, I dedicated my novel Unfriendly Persuasion to Harve, and sent him a copy. A week or so later, I received a hand-written letter from Harve, thanking me for the honor, and expressing gratitude that, late in his life, he was being told he’d made a difference to someone with talent. I knew that Harve was in poor health at the time. The fact that he not only acknowledged my gesture, but hand-wrote a letter to me and once again validated my creative efforts, meant the world to me.

Harve was a talented person, and a warm and encouraging person. Most people aren’t both. Often, when you meet the author of a book you loved, or the people behind a TV show or movie you loved, you’re disappointed to discover that they don’t live up to your expectations. They don’t share the dreams that their work brought to life in you. They’re only in it for the money, or they’re so self-absorbed that they have nothing personal to share with you one-on-one.

Harve was everything you could have asked him to be. Once I’d met him, going back to watch his work was a whole new experience. The life, the compassion, the humor of the Bionic shows and the Trek movies was also alive in Harve. Steve Austin was a typical 70s action hero, yes, but he was also a man of great humor and compassion. Jaime Sommers was stronger than ten men, but showed her vulnerability and fear, and let us know it was okay to be afraid and vulnerable. You could do that and still kick ass. And 50-something James T. Kirk was questioning his past, his decisions, his place in the universe, but he still could face the allegedly no-win scenario, and he still felt young. Harve’s heroes were people, and that made them all the more special.

Harve, I can only end this by saying I’m grateful for your life’s work, I’m grateful that I had the chance to know you. You left this world a better place than you found it. As the surgeons took Steve Austin and changed him, so you have changed us. You’ve made us stronger. You’ve made us better than we were before.

That’s worth a lot more than Six Million Dollars, my friend.

Most especially this: “The moral wasn’t, ‘Humankind is an evil disease in the universe, and its technology is destructive.’ It was, ‘Humankind can make mistakes while developing technology, and Humankind can also fix those mistakes, with courage, intelligence and morality’.”

Well said.