Note: This is really long, comparatively, and contains spoilers for a film you’ve had 40 years to see. I apologize for nothing.

Before I get to discussing the film, a brief, perhaps self-serving anecdote:

I was performing, onstage at the Farpoint convention, with my group, Prometheus Radio Theatre. Lance Woods and I were playing Jim Kirk and Spock, as if they were roles essayed by Bing Crosby and Bob Hope in a (fictional) 1940s film called The Road to Orion. I was very proud of my script, and we had a great time with a lot of celebrity guests and in-jokes for the audience.

In that audience was one James Callis, star of Battlestar Galactica and the Bridget Jones films. Mr. Callis had been invited to perform, had declined, but had stayed to watch. After the show, his agent told me that he had spent the performance pointing wistfully at the stage and saying, “But I want to do that!”

Told you it was self-serving.

I can think of few forms of praise higher than being told that your work makes someone else say, “I want to do that!” When I first saw Richard Donner’s Ladyhawke, in 1985, it had that effect on me. I saw on the screen a story I desperately wished I could have told. And I promptly forgot that, and spent the ensuring years thinking of the film only when engaged in arguments about its soundtrack. (Best. Soundtrack. Ever. Fight me.)

But this past Friday, wanting to kick back and watch TV, my wife Renee and I chose Ladyhawke over all the newer content on our streaming services, probably because of the sheer novelty of seeing it show up on the top of Prime’s recommended content list.

I spent the next two hours thinking, “But I want to do that!”

Yeah, I doubt the late Mr. Donner, the late Mr. Hauer, Mr. Broderick or Ms. Pfeiffer would find their universes shaken by my sentiment. Nonetheless…

I recaptured, in those two hours, the feeling that a story had engendered in a 19-year-old who wanted to be nothing else but an author, a playwright, a screenwriter, a storyteller. It wasn’t the first film or book or comic to have that effect on me, and it wouldn’t be the last. But I had forgotten–or maybe I had never even realized–that it’s the one that incorporated all the elements of what I would later think of as a Steve Wilson story.

It was an unlikely film for me to fall in love with. First, I don’t like fantasy. I studied the Arthurian legends in college and found them dull. I could never get even five pages into Tolkein. When I saw the fliers in the Student Union for a free preview of a fantasy film, with a photo of the replicant from Bladerunner and the kid from War Games sitting together on a horse, I just thought, “Meh.” (Or some word to that effect that was more in vogue for 1985.) But my friend Beatrice, one of my few remaining friends from high school, now that I was 19, and, you know, mature, wanted to see it. Now, Beatrice spoke positively of Beastmaster. Our taste in films and fiction never did and never will 100% overlap. Her wanting to see Ladyhawke did not lift it out of the “meh” category; it just made me willing to go see it in order to spend an afternoon with a friend I didn’t see that often. I approached it with some dread.

And then the music started. It was different enough that I noted the name of the composer. Didn’t recall Andrew Powell, but I thought, “This doesn’t sound like a fantasy film. It sounds like–” And there was the credit: “Engineered by Alan Parsons.” My single favorite musician had worked on a film score, written (I went home and realized) by the arranger and conductor for his albums.

It’s amazing how kindly disposed a fantasy antagonist can become to a fantasy film when his favorite band is involved.

But it wasn’t just the music that grabbed me, not by a long shot. Nor was it the performances of some serious talent: Matthew Broderick, Michelle Pfeiffer, Rutger Hauer and Leo McKern. It was story elements that I either didn’t expect to see, or didn’t expect to see so well-handled. At nineteen, I probably didn’t realize half of this. It’s taken me forty years to put it all together, but these are the things crucial to a story, for me, especially if it’s one I’m telling or writing.

Love – Okay, most stories are about love in some form. Honestly, the love element of Ladyhawke is almost rom-com: Two lovers have an insurmountable problem that keeps them from being together. Due to a curse, he’s a lycanthrope, changing into a wolf, not at the full moon, but with each sunset. She, on the other hand, turns into a hawk when the sun rises. They never see each other in human form. Hilarity ensues. Actually, violence and heartbreak ensue. But the love element of Ladyhawke is the sort of romantic love I believe in, the sort that’s strong enough to overcome the greatest adversity, be it a Satanic curse or the far-more-daunting challenge of staying married for the rest of your lives while simultaneously managing to not strangle your family members. Love has got to be strong and determined. Lovers have got to be stubborn–with fate, not so much with each other.

Honor – Etienne Navarre is a man on a quest, appropriate to a story of Medieval chivalry. He explains carefully to Philippe the Mouse, who becomes his page, that each of his forbears have used the family sword to distinguish themselves on the field of honor. He must do so as well, and add a jewel to the haft of the sword to symbolize his accomplishment. Navarre must kill a man. Lest you think the story is holding up murder as a noble act, the man he must kill is literally in league with the devil. The Bishop of Acquila placed the curse on Navarre and his love, Isabeau, because the Bishop wanted Isabeau for himself. We see, in the course of the film, more than a few people brutally slain in the name of the Bishop. He’s a dictator, a murderer, and would-be a rapist.

Navarre displays a typical hero’s stubbornness in carrying out his mission, insisting on moving forward even when his friends tell him he’s wrong to do so. The twist? He is wrong. If he kills the Bishop, the curse will go on forever; and he’ll never see Isabeau again, except perched on his arm as a faithful hawk. Heroes have to be stubborn. Jim Kirk had to be stubborn when the spores of Omicron Ceti III took over the minds of his crew with pure happiness. He had to resist in the name of free will. John Koenig had to be stubborn when wandering Moonbase Alpha was on course to collide with a planet, and he knew that the collision would not destroy, but benefit the inhabitants of both. Lazarus Long had to be stubborn when… oh, dammit, Lazarus Long just had to be stubborn. But you don’t live tens of centuries if you’re getting everything wrong.

Stubbornness is essential to honor, as it is to love, because both demand that we don’t give up, and the world nearly always demands that we do. The world, all things considered, doesn’t really like love or honor. But Ladyhawke shows the downside of the hero’s stubbornness, and still allows him to succeed.

Loyalty – It’s loyalty that saves Navarre. He’s being a butthead. He wants to give up on true love and just get revenge. He thinks that’s honorable. He’s also discouraged. But Isabaeu, Phillipe, and the defrocked priest Imperius don’t let him give up. Loyalty makes our friends and family love us when we need it most and deserve it the absolute least. Together, the three conceive a plan and trick Navarre into seeing that it might work.

Humor – This film is not a comedy, but Matthew Broderick rarely fails to bring a smile. Nor does Leo McKern, the quintessential eccentric old gentleman. For me, though, the funniest line went to Rutger Hauer, when he found his page chopping wood with his great great grandfather’s blade: “This sword has been in my family for five generations. It is never known defeat… till now.” Maybe you had to be there, but I like wry dialogue.

Faith – Ladyhawke is a story of faith–faith in God, faith that good will triumph, faith in each other. A lot of people find faith old-fashioned and naive. I nearly always incorporate religious faith in my stories, and sometimes readers or listeners have told me that puts them off. My experience, though, is that there are two kinds of fundamentalists: Those that believe that God has revealed unto us the truth to its last detail, and those who believe that Science is always right. Both types of fundamentalists dwell in a world of certainty, because they have to. The science fundamentalist actually will admit that science can be wrong, but he still has absolute confidence that, with enough data, the question has been answered and no one can dispute the results. “The science is settled,” is what he says in place of “Amen.”

A lot of us, though, are comfortable enough with uncertainty. We don’t need every question answered. We can navigate the rapids well enough, if we have faith in something. That something doesn’t have to be God; but God is the symbol most people understand for the object of human faith. It’s nothing more or less than the belief that all will work out for the best, somehow, and that the love in our lives is justified.

Wrestling with morality – Navarre’s determination to kill is never questioned, except as a matter of strategy. In the end, he kills the Bishop and we all cheer. Lots of other moral questions are posed in Ladyhawke, however. Phillipe is a thief and a liar. Throughout the film, he has a running dialogue with God about just that. He asks why, when he occasionally tells the truth, things go badly. He twits at God for allowing the appearance of moral ambiguity. He lies and steals many times in front of us. We see why he would have been in prison, as he is in the beginning of the film; but we see just as clearly that he doesn’t deserve to hang, as the Bishop planned. There is good in him, and he shows us that too. Society has given up on Philippe, but truly good people (in the persons of Navarre and Isabeau) do not.

Similarly, Imperius has broken his vow by violating the secrecy of the Confession. He knew, before the curse was placed, that Navarre and Isabeau were in love. That knowledge, because of the Bishop’s feelings for her, was a grave threat to both. Imperius got drunk and let the cat out of the bag, causing all the events seen in the film. Nonetheless, Navarre knows, when Isabeau is mortally wounded, that only the old priest can save her. Loyalty and faith again come into play. Grudgingly, Navarre gives the old man a chance to redeem himself.

Corrupt Authority – If you’ve ever read or heard a story of mine, you know what I think of most authority. At best, it’s a necessary evil; and it’s rarely necessary. Ladyhawke tears established authority to shreds. The Bishop is literally diabolical. His Captain of the guards is a sadist and a murderer. There is no justice in the prisons of Acquila. The Church cannot be trusted, because old drunken priests let secrets leak. The only respected authority shown in this story is that of each of the individual players when they’re acting out of love and taking responsibility for their own actions. Established authority never does either of those things.

Just Enough Science – I suppose I have a scientific mind. I have a scientific degree and was raised by an engineer. I love classic science fiction, though I don’t read most of the new stuff. But I get bogged down if there’s too much science in a story. Ladyhawke is mostly a magical fairy tale, but it has one sliver of science. Imperius, demonstrating that early clerics were the first to bring us scientific discovery, uses crude astronomical knowledge to predict an eclipse. During those few minutes of “A day without a night, a night without a day,” Narvarre and Isabeau, both human, can stand before the Bishop and thus break their curse. In a small way, it shows that knowledge and the rational intellect can triumph over ignorance, superstition, and evil.

The final moments of the story are very interesting to me. Navarre rides into the cathedral, confronts the bishop, meaning to kill him. The eclipse happens, Isabeau enters. They face their tormentor and the curse is broken. The Bishop, enraged, tries to kill Isabeau and dies spectacularly at the point of Navarre’s thrown sword.

Now, you could say Navarre kills in self-defense here; but I think the entire congregation knows that the guy who rode a freaking horse into the sanctuary, killing several people on the way, and pointed a sword at the highest official in town was not there to pay his taxes. In modern parlance, Navarre is a terrorist and an assassin. But when all is said and done, the priests and parishioners gather around the triumphant couple and… wave?

Well, I guess Navarre was popular when he was Captain of the guard in Acquila, and I guess everyone pretty much agreed the Bishop was a bad dude. But I would love to see the sequel where some officious little snot charges Navarre with crimes against the State.

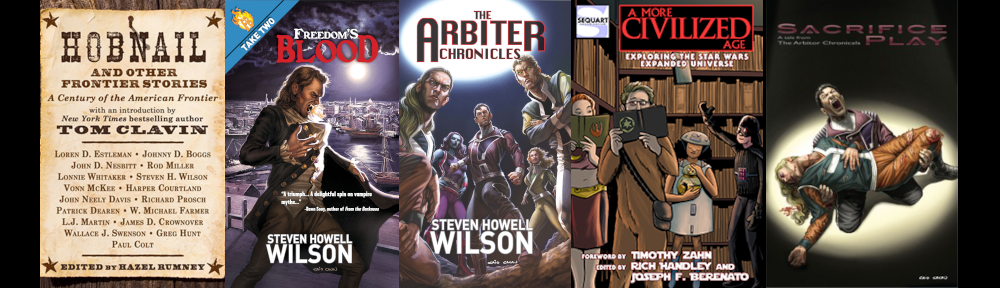

There you have it. All the things I love about a film that’s turning 40 this year in which I turn 60. I now realize how many of those elements have advised my storytelling. And I guess I’m a bit… wistful… that my storytelling never led to a Hugo or Nebula Award (though the Parsec and the Mark Time are much appreciated.) It never landed me on the New York Times Bestseller list, or even the Amazon top ten in any category. It never made me rich.

But It’s made people laugh. It’s made people cry. It’s made people think. It got me invited to and involved with conventions. It led me to serve as an actor, a director, a technician, a children’s librarian, a politician, a convention organizer, a youth pastor, a member of various boards… It’s not even a stretch to say that my storytelling made me a husband, a father and a grandfather. It directly did. (Yes, one day, I’ll put that story in writing.)

When I look at the people who have been successful in my originally chosen profession, I largely see people who threw themselves into it wholeheartedly. They went hungry, they took endless workshops, they put themselves in front of editors at conventions, they worked their asses off at one thing, and got really good at it.

I’ve worked my ass off–trust me, there’s not much of it there… but not at one thing. Not even the thing I love doing most. You could say I’ve let myself be distracted, that I lost (or never had) focus. And so I never really wrote my best version of the story with all these elements. I never submitted it to an agent. It was never bought by a publisher or a studio. It never made me rich or famous. You could say I blew my chance to make my own Ladyhawke.

But also maybe… maybe I look at all those things I’ve done… Maybe I see how they were advised by all those things I loved in this story and tried to incorporate in my work, no matter what work… And I realize…

Maybe the last almost-sixty years have been the story I wanted to tell when I said, “I want to do that!”

If so, to those of you in the audience, I hope it has entertained.