As with all of my blog series, the FIAWOL blogs are written weeks in advance. But I was a day late posting this week because the online science fiction world was exploding with news about Chris Hardwick and Chloe Dykstra. I have thoughts about that news, and about the #MeToo movement at large. So I took a day out and tried to write about them. This was the second time in recent months I’ve tried to do so. And, just as with my first attempt, I wrote about 2500 words, re-wrote a second draft… and then decided I wasn’t ready to share my very personal thoughts on the subject with the world. Maybe I’m a coward, and maybe I have good reason to be. You see, my morality doesn’t work like most peoples’.

As with all of my blog series, the FIAWOL blogs are written weeks in advance. But I was a day late posting this week because the online science fiction world was exploding with news about Chris Hardwick and Chloe Dykstra. I have thoughts about that news, and about the #MeToo movement at large. So I took a day out and tried to write about them. This was the second time in recent months I’ve tried to do so. And, just as with my first attempt, I wrote about 2500 words, re-wrote a second draft… and then decided I wasn’t ready to share my very personal thoughts on the subject with the world. Maybe I’m a coward, and maybe I have good reason to be. You see, my morality doesn’t work like most peoples’.

Which is a good segue for this piece that wasready for publication yesterday…

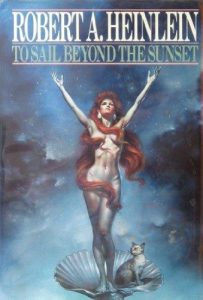

This was Robert A. Heinlein’s final book, moodily (and prophetically) titled with a quote from Tennyson’s “Ulysses” about old age and death. But this book is not at all about old age or death, it’s about life, about living it wisely and passionately, about defying death, and about maintaining youth.

It’s also about a lot of incestuous sex, because Heinlein loved to rattle cages. Consequently, a lot of fans were turned off more and more by Heinlein with each new, taboo-challenging book he released. I won’t go into a lot of detail discussing the topic of incest in this book, but I’ll say this: this book couldn’t exist without incest. It’s a sequel to Time Enough for Love, and a partial re-telling of that work from another character’s perspective. I’m sure it wasn’t the first time that device was used, but this book long pre-dates Ender’s Shadow and its series of retellings of books as sequels of sequels of sequels.

In Time Enough for Love, Lazarus Long, the oldest man alive, goes back in time and falls in love with his mother, Maureen Johnson. In The Number of the Beast,Lazarus’s friends and family go back in time with him again to rescue Maureen before her untimely death at just 100 years of age, so that he can marry her good an proper, living, literally, happily ever after. (It’s important to know that Lazarus and Maureen are Howards, products of a eugenics experiment in which children were bred for long lifespans. Lazarus, it turned out, was a mutant who naturally lived for centuries, before medical technology and antigeria kept him going for millennia.

Incest, Heinlein was positing, is only taboo because it increases the likelihood of reinforcing genetic defects. Intellectually, there should be nothing “gross” about it, anymore than sex itself is “gross” to us. It’s just sex. Emotionally, of course, there’s another story, and it’s not one Heinlein tells here. The emotional consequences of incest are also tied up in imbalances of power between family members, and there is no imbalance of power when two or more Heinlein characters are in the room. They’re all in charge, and they’re all right. Differences will be solved with amusing banter and the occasional poker game. Figuratively. They bluff and call each other a lot.

Come to that, all taboos could be argued to be rooted in practicality. Homosexuality, it’s been suggested, became taboo because the tribe needed to grow in strength in order to resist its enemies, so wasting a man’s seed was a bad thing to do. A man needed to impregnate women, early and often, so we had boys to work the fields and fight the infidels, and girls to bear more children. Various dietary taboos and customs are about keeping food sanitary and avoiding illness.

Morality is practical. It protects the group and the individual. Sometimes it protects one at the expense of the other. Then does it become bad morality? What if conditions change? What if we don’t need more babies? What if sanitation and refrigeration make it okay to eat shrimp? Does morality need to be updated? Reconsidered? And who does the updating and reconsidering?

Heinlein said yes to the first questions. To the second, he said, “Why not you?”

So there’s a wonderful scene in “Sunset” where Maureen, an amoral hellion if ever one lived, is given an assignment by her father, Ira Johnson:

When I was still quite young, my father said to me, “My beloved daughter, you are an amoral little wretch… If you are not to be destroyed by your lack, you must work out a practical code of your own and live by it.”

When Maureen proposes to live by the Ten Commandments, her father declares, “The Ten Commandments are for lame brains. The first five are solely for the benefit of the priests and the powers that be; the second five are half-truths, neither complete nor adequate.”

“Analyze the Ten Commandments,”he orders her. “Tell me how they should read.”

The result of the enterprise is that Maureen develops her own rational morality, which she completely understands, and is then able to live by. Indeed, the fact that her father calls her “amoral” is interesting. If a person is without morals, but has put together a practical code of rules to follow, how are they “amoral?” Aren’t morals just a code of rules to be followed?

The difference, I infer, is that word, “Practical.” If you insist that your morality make sense, then you are not, in Ira Johnson’s tongue-in-cheek opinion, moral. Not even if you follow your practical code to the letter, day in and day out. To be moral, in the eyes of the Mrs. Grundys of the world, you must accept the moral code which is dictated to you, without question, whether or not it makes sense. Indeed, you are to accept it as the one moral code, ordained by God, even though you know that there are other moral codes with which it differs. You arenever to ask whence sprang the other moral codes.

(If you’re not familiar with her, Mrs. Grundy is the archetypal busybody neighbor and moralist, who dates back to the late 18thCentury.)

Further, in the eyes of Mrs. G., morality is a code which is not written down or taught like mathematics, it is something everyone is “just supposed to know.” When I was much younger and asked my mother to explain moral principles to me, she was fond of saying, “Well, if you don’t know, then I can’t explain it to you.” I take this now to mean that my firmware was in need of an upgrade. There was some piece of race memory that was supposed to have been implanted in my brain at birth but was not.

I’ve encountered this belief often, especially among parents who believe that their children should never indulge in behaviors that they, themselves, model:

Parent: “I can’t believe my son got drunk at the New Year’s Party! He’s twelve years old, what was he thinking?”

Me: “He was thinking that you and your friends were all drunk, and it looked like fun.”

Parent: “But he’s a child! He should know better!”

Me: “If the adults don’t know better, how should the children?”

Parent: If you don’t know, then I can’t explain it to you.

Ira Johnson was a heretic. He believed in explaining to his daughter that which she did not know, but only if she tried to figure it out for herself first.

And she does. Some examples…

Her First Commandment rewrite is “Thou shalt pay public homage to the god favored by the majority without giggling or even smiling behind your hand.” (Thou shalt have no other gods before me.)

At a very young age, Maureen has developed a cynical attitude towards the religious beliefs of the people around her. She has no doubt seen the hypocrisy, pettiness, distrust mean-spiritedness and puritanism with which many of the faithful complicate their faith. It’s hard to be moral when the people meant to teach morality come off as nasty, pompous fools.

She misunderstands the Second Commandment, “Thou shalt make no graven images…”, thinking it’s about censoring licentious works. Her father explains that it actually means not to treasure worldly creations to the point that they become gods. Then he dismisses the Second Commandment as pointless. The third she translates as “Don’t swear.” Her father adds “Thou shalt not split infinitives or dangle participles.”

And of course, there’s, “Thou shalt not commit murder. ‘Murder’ means killing somebody wrongfully. Other sorts of killing come in several flavors and each sort must be analyzed. I’m still working on this one, Father.”

Heinlein’s characters did not shy away from killing, if they thought someone was out to kill them first.

There’s a long discussion of adultery, featuring a Heinlein staple, the idea that, in a healthy marriage, one partner will often not only give permission to the other to “jump the fence,” but will even aid and abet the extra-marital affair.

Especially memorable, Maureen rewrites “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor” as “Don’t tell lies that can hurt other people… but since you can’t guess ahead of time what harm your lies may do, the only safe rule is not to tell any lies at all.”

Her father adds:

“A liar is worse to have around than a thief… yet I would rather cope with a liar than with a person who takes self-righteous pride in telling the truth, all of the truth and all of the time, let the chips fall where they may – meaning ‘No matter who is hurt by it, no matter what innocent life is ruined.’ Maureen, a person who takes smug pride in telling the blunt truth is a sadist not a saint.

But I think this is the exchange that has always stood out most for me:

“Thou shalt not steal. I couldn’t improve that one, Father.”

“Would you steal to feed a baby?”

“Uh, yes.”

“Think about other exceptions; we’ll discuss it in a year or two. But it is a good general rule. But why won’t you steal? You’re smart; you can probably get away with stealing all your life. Why won’t you do it?”

Maureen concludes: “I don’t steal because I’m too stinking’ proud!”

Her father is pleased with that answer. “Exactly! Perfect. For the same reason you don’t cheat in school, or cheat in games. Pride. Your own concept of yourself. ‘To thine own self be true, and then it follows as the night from day–'”

“‘- thou canst not then be false to any man.’ Yes, sir.”

Dr. Johnson goes on to tell her that, “A proud self-image is the strongest incentive you can have towards correct behavior. Too proud to steal, too proud to cheat, too proud to take candy from babies or to push little ducks into water. Maureen, a moral code for the tribe must be based on survival for the tribe… but for the individual correct behavior in the tightest pinch is based on pride, nor on personal survival. This is why a captain goes down with his ship; this is why ‘The Guard dies but does not surrender.’ A person who has nothing to die for has nothing to live for.”

This jibes with the idea that morality is how you behave when no one is looking, but Ira Johnson also makes an important distinction here: a moral codefor the tribe vs individual correct behavior. The needs of the many, the needs of the few or the one. And the way Heinlein lays it out here, there’s an implication that one is low morality—selfish, practical, necessary—and one is high morality—idealistic, high-minded, noble.

Nobility, as opposed to common morality, is often evident in Heinlein’s works. He’s very tolerant of human foibles. Many of his characters—especially the incidental ones—are flawed, and their flaws are accepted and tolerated by moral arbiters like Lazarus Long, Jubal Harshaw or Maureen Johnson. For their part, the moral arbiters make no high-minded claims to moral superiority. Lazarus frequently describes himself as a coward, his family members call him dishonest and untrustworthy, and his mother calls herself “an amoral wretch.” They are, nonetheless, a kind of nobility, because they develop their own morality.

The best of humanity does this. The rest follow the common morality, which is there for the purpose of protecting the tribe, the species, the race, not the individual. The Captain goes down with his ship because his pride trumps his fear. Or is it because his fear of disgrace trumps his fear of death? The grunt may go to war because his common morality tells him that his nation’s life is more important than his own, or because his pride tells him that the best man is the one who puts his life on the line to protect others.

Which is motivating them and when? Nobility or base morality? You have to know and evaluate a person to even begin to address such a question. In these days of standardized tests, electronic performance evaluations, labels and identity politics, most people don’t know the first thing about evaluating the moral fitness—or even the professional competence–of another human being. Indeed, most people are scandalized by the very idea of “passing judgment” on another.

I said that the “best of humanity” develops its own moral code. Does that mean that I’m saying some humans are better than others? I won’t touch that un-quantified question. Some humans are better violinists than others. Some humans are better surgeons than others. Some humans handle a firearm better than others. Letting those “others” play the solo, remove the kidney or hold the loaded gun could have disastrous results. So some humans are prone to develop their own moral code, and others are prone to, without really thinking about it, follow the code that’s laid down to them. I would argue that the former are the ones I would want exercising leadership, because they’re the only ones capable of seeing past rote memorization and actually innovating.

Yes, there’s elitism here, but it’s an elitism based on merit.

In Ira’s view, those who develop their own morality are also motivated by selfishness, but it’s s selfishness rooted in a desire for excellence, not a selfishness rooted in fear of others. Those who follow the traditional law are motivated by a desire to fit in, to not be judged, to avoid shame and repercussions. And yet it is, in my experience, that larger group which cannot explain the motivations behind their morality that becomes the most incensed when that morality is challenged. The Maureens and Iras of the world look on sin with more humor and forbearance.

I wonder, is that why Jesus was reputed to be so patient?

But it’s interesting to note that Ira does not offer this morality counseling service to all his children. A cynic might say that he offers it only to the daughter who harbors incestuous longings for him, or even, perhaps, that the daughter felt no compunctions about having incestuous longings for her father because he filled her head with this poisonous nonsense about morality making sense. Whatever the reason for that taboo-shattering component of their relationship, it’s clear that Ira was choosing an elite group of two out of the dozen-or-so members of his immediate family.

I don’t approve of family favoritism. In fact, when I’ve encountered it in my life, I’ve usually been disgusted and even enraged. As parents, we are the first shapers of our children’s self-image and self-esteem. Picking one child for special favors and making it obvious to the others is, in my eyes, an abdication of parental responsibility. My own mother once said to me though, “I’ve never treated all of you equally. I’ve tried to give each of you what you needed.” And, sometimes, that practice can look like favoritism. Who decides if it is? Tough question. I guess each of us has to decide things like that alone.

Scary, isn’t it? And choosing your own morality is scary, especially as it tends to separate you from others—the majority of others—who don’t do it. Their sense of right and wrong comes from the rules laid down for them, not from reason. It tends to make their responses to moral questions emotional, rather than rational. If you’re attacking a moral problem rationally, it can make you pretty lonely.

But I’ll talk more about that when I address science fiction’s favorite bastion of rationality, a certain green-blooded, pointed-eared half-Vulcan.

Hmmm… “Yes, there’s elitism here, but it’s an elitism based on merit.” And just what is ‘merit’, one wonders — and who gets to determine the definition? Abraham Grace Merritt, perhaps? One does note that his second wife was Eleanor Johnson — of the Johnson Family, one presumes…

Just wondering, not criticizing. Thank you for your well-written analysis — it was a pleasure to read.

Ooh, nice reference! And now you’ve expanded my reading list!

In fairness, we don’t really know what he told his other kids. Maybe they needed special advice of their own?

Quite possibly. As I said, meeting a special need can look like favoritism. That doesn’t mean it is.