September 15, 2017

Dear Daddy –

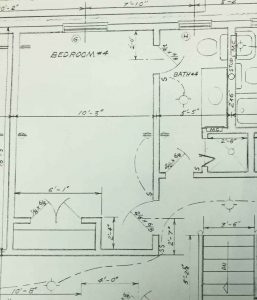

This week I’ve been coming into the home stretch on the blue bathroom—“The Boys’ Bathroom.” You designed it with a shower and two sinks, with a door that opened into Charles’s bedroom. I guess the senior brother was thought to deserve the privilege of a private entrance into the bathroom in the middle of the night, or early in the morning. My bedroom was to be around the corner. The two sinks would have allowed us to brush our teeth—or later shave—at the same time.

This week I’ve been coming into the home stretch on the blue bathroom—“The Boys’ Bathroom.” You designed it with a shower and two sinks, with a door that opened into Charles’s bedroom. I guess the senior brother was thought to deserve the privilege of a private entrance into the bathroom in the middle of the night, or early in the morning. My bedroom was to be around the corner. The two sinks would have allowed us to brush our teeth—or later shave—at the same time.

As with most of your plans for the house, this arrangement never came to be. The bathroom was never finished. As I write this, the toilet, sinks, plumbing fixtures and tile are still in their boxes, only recently moved out of storage in the roughed-in shower cubicle, and the back corner of the East General Purpose Room—“Susan’s General Purpose Room,” now to be Ethan and Jessica’s room.

You recanted the extra door, the one into Charles’s room. There’s some cracking in the sheetrock above it, where the house settled. You told me that your father had tried to get you to do the headers of the supporting walls differently—was it doubling up the two-by-fours? You didn’t do it, and, decades later, you were sorry. “I should have listened to my father,” you said. You almost never said that.

Your father, you told me, was a temperamental man. I knew him, of course. I was 23 when he died. He did have a temper. He didn’t seem to like people very much. You said he used to throw things, like electrical boxes, when he got frustrated. He’d damage them, and you’d go retrieve them and pound them back into shape. You never understood how he could be so destructive, taking out his anger on objects that had never done anything to hurt him.

Well, now, an object can’t do anything to hurt someone, can it? But then you always seemed to have more sympathy for objects than you did for people. I guess that’s why you never threw anything away, and why you would berate me for, like your father, taking out my anger on things. “At least I never hurt people,” I think I probably said to you more than once.

You’d planned to open up that wall and reinforce it, to correct your earlier mistake. That’s why the room was never painted, the bathroom never finished. Just another set of circumstances that slowed you down, frustrated you. Mother told me the other day that she’d found a letter you’d written to your brother Bill, in which you’d told him that you spent so much time getting ready to do a job in the house, that, by the time all the supplies were in place, you had no energy to do the work. I sympathize.

Why did you have that letter? Didn’t you mail it? Did you not want to admit weakness to your little brother, who probably idolized you growing up? Or is it something else you meant to do, and didn’t?

“I can do that after while,” I can imagine you saying. You said that a lot. “We’ll do that after while. After my food settles. After I watch the news.”

You thought you had all the time in the world.

Charles and I never lived in those two rooms at the same time. He moved “upstairs,” leaving our communal residence in the Family Room, in 1971. I stayed downstairs, first with you and Mother, and then in my own bedroom, until I went to college in 1983. You moved me upstairs to “my” bedroom, as designated on the plans, while I was living in College Park. You needed the room I’d been living in as an office for your new consulting business.

By that time, Charles had moved down the hall to the much larger West General Purpose Room. None of those rooms were painted, and the carpets on the floors left plywood exposed at the edges. At least they had electricity.

The blue bathroom became a storeroom, full of the supplies that would be needed to finish it, full of odd sheets of plywood and sheetrock, eventually also full of data terminals, printers and plotters. When I went to clean it out in the Spring of this year, there were also baby supplies and a wheelchair stored there. You’d ordered a wheelchair in case Mother ever needed one. She still doesn’t. You did, but you refused to use it.

Only the rest of us were allowed to be weak.

Once I had it empty, it was a plywood floor, a plywood cubicle for a shower, with holes cut for the showerhead and faucets, a loose piece of plywood leaning against the wall where the sinks and toilet would go. You were going to tile the lower half of that wall, and you believed in tiling over plywood. That’s not done now. They use a cancer-causing cement board instead. It’s okay, they say, as long as you cut it outdoors and wear a mask.

Once I had it empty, it was a plywood floor, a plywood cubicle for a shower, with holes cut for the showerhead and faucets, a loose piece of plywood leaning against the wall where the sinks and toilet would go. You were going to tile the lower half of that wall, and you believed in tiling over plywood. That’s not done now. They use a cancer-causing cement board instead. It’s okay, they say, as long as you cut it outdoors and wear a mask.

Cancer? In my family’s house? Not sold.

But Renee convinced me that I didn’t want to tile that whole room, as you’d planned. I replaced the plywood with sheetrock, and frustrated myself with my first attempt to line up the holes needed for plumbing and electrical boxes. I failed epically on the electrical boxes. You hadn’t installed them, so I did it myself. The light box was easy. I just mounted it 18” from the ceiling like the ones you’d already mounted in the downstairs bathroom and Susan’s bathroom next door (though that was just a box, with no light installed yet.)

I don’t know where you had planned to put the extra outlet. You’d just left a coil of wire (live wire, thank you) hanging from the ceiling. The mirror you’d bought was five feet wide, and going to fill the entire space over the sinks, all the way from the counter top to the light fixture. I guess the outlet was going to go over by the toilet? Not an idea I cared for. I made an executive decision to not use your five-foot mirror. It’ll fit downstairs in Mother’s bathroom, where there are no outlets by the sink.

I don’t know where you had planned to put the extra outlet. You’d just left a coil of wire (live wire, thank you) hanging from the ceiling. The mirror you’d bought was five feet wide, and going to fill the entire space over the sinks, all the way from the counter top to the light fixture. I guess the outlet was going to go over by the toilet? Not an idea I cared for. I made an executive decision to not use your five-foot mirror. It’ll fit downstairs in Mother’s bathroom, where there are no outlets by the sink.

So the outlet is now placed dead center between the two sinks, and, well, I’m ashamed to tell you I muffed the measurement for the outlet holes in the sheetrock. I had to do some extra trimming on one side, and I had to use tape and joint compound to cover the extra-large hole on the other.

As George Lazenby said, introducing his only appearance as James Bond, “This never happened to the other fellow.”